Hopefully by now, you've read about the signs and reversal of overtraining. Now let's look at why and how to train intelligently in-season. A well-designed in-season program should a) prevent overtraining and b) improve strength and power (for younger/inexperienced athletes) or maintain strength and power (older/more experienced lifters).

First off, why even bother training during the season?

1. Athletes will be stronger at the end of the season (arguably the most important part) than they were at the beginning (and stronger than their non-training competition).

2. Off-season training gains will be much easier to acquire. The first 4 weeks or so of off-season training won't be "playing catch-up" from all the strength lost during a long season bereft of iron.

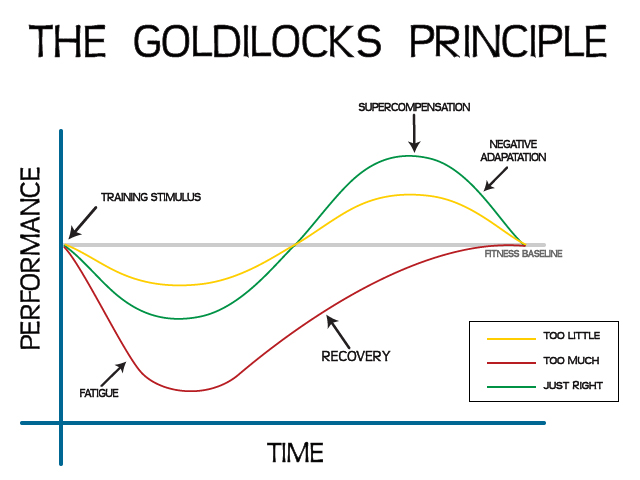

I know that most high school (at least in the uber-competitive Northern VA region) teams require in-season training for their athletes. Excellent! However, many coaches miss the mark with the goal of the in-season training program. (Remember that whole "over training" thing?) Coaches need to keep in mind the stress of practice, games, and conditioning sessions when designing their team's training in the weight room. 2x/week with 40-60 minute lifts should be about right for most sports. Coaches have to hit the "sweet spot" of just enough intensity to illicit strength gains, but not TOO much that it inhibits recovery and negatively affects performance.

The weight training portion of the in-season program should not take away from the technical practices and sport specific. Here are a couple of things to keep in mind about the program, it should:

1. Lower volume, higher intensity-- this looks like working up to 1-2 top sets of the big lifts (squat or deadlift or Olympic lift), while maintaining 3-4 sets of accessory work. The rep range for the big lifts should be between 3-5 reps, varied throughout the season. The total reps for accessory work will vary depending on the exercise, but staying within 18-25 total reps (for harder work) is a stellar range. Burn outs aren't necessary.

2. Focused on compound lifts and total body workouts-- Compound lifts offer more bang-for-your buck with limited time in the weight room. Total body workouts ensure that the big muscles are hit frequently enough to create an adaptive response, but spread out the stress enough to allow for recovery. Note: the volume for the compound lifts must be low seeing as they are the most neurally intensive. If an athlete can't recover neurally, that can lead to decreased performance at best, injuries at worst.

3. Minimize soreness/injury-- Negatives are cool, but they also cause a lot of soreness. If the players are expected to improve on the technical side of their sport (aka, in practice) being too sore to perform well defeats the purpose doesn't it? Another aspect is changing exercises or progressing too quickly throughout the program. The athletes should have time to learn and improve on exercises before changing them just for the sake of changing them. Usually new exercises leave behind the present of soreness too, so allowing for adaptation minimizes that.

4. Realizing the different demands and stresses based on position -- For example, quarterbacks and linemen have very different stresses/demands. Catchers and pitches, midfields and goalies, sprinters and throwers; each sport has specific metabolic and strength demands and within each sport, the various positions have their unique needs too. A coach must take into account both sides for each of their positional players.

5. Must be adaptable --- This is more for the experienced and older athletes who's strength "tank" is more full than the younger kids. The program must be adaptable for the days when the athlete(s) is just beat down and needs to recover. Taking down the weight or omitting an exercise or two is a good way to allow for recovery without missing a training session.

A lot to think about huh? As a coach, I encourage you to ask yourself if you're keeping these in mind as you take your players through their training. Athletes: I encourage you to examine what your coach is doing; does it seem safe, logical, and beneficial based on the criteria listed above? If not, talk to your coach about your concerns or (shameless plug here, sorry), come see us.