Tips For Training While Traveling

Today's post is brought to you by Mike Snowden, traveler extraordinaire. The summer is a wonderful time to get out and travel for some vacation time. If you’re like most of us here at SAPT, you hit the road or jet set with a bar, some plates, a few kettlebells and a prowler. For those of you who may have forgotten a few of these trip essentials while you were packing, you may have to get a little more creative to keep up with your training. Below we’ve put together a few short workout ideas based on what you may have available to you.

Level 3- A Loaded Hotel Gym

If you are lucky enough to find that your hotel gym is fully stocked like SAPT (sadly, without the amazing staff) get in there and take full advantage of it. To ensure you are not spending your entire vacation in the gym, take a couple of days to train the body as a whole. In a recent post, Kelsey spoke about training 5 movement patterns in the same workout. The order of these movements and the exercises can vary but focus on completing an exercise from each group:

1) Hinge- Ex: RDL, Kettlebell Deadlift

2) Squat- Ex: Goblet Squat, Step back Lunge

3) Press- Ex: Bench Press, Floor Press, Overhead Press

4) Pull- Ex: TRX Row, Pull Up, Chest Supported Row

5) Carry-Ex: Farmers Walk, Waiter Carry

Level 2- The Gym That Looked Better Online

If you arrived on site to find your hotel gym is a room with a flat stability ball and a few dumbbells don’t worry because things are still looking up. With the limited tools you can still focus on the same principles as the level 3 crowd. An important change to make here is pay more attention to the tempo of each reps. Now you can get creative and add some isometric holds. If you want to really have some fun, slow your repetitions down by taking 3-6 seconds to lower followed by 3-6 seconds to lift the weight.

Level 1- A Hill/ Stairs

This is level 1 but it’s still pretty awesome. Running a hill or hitting some stairs are great ways to expend some energy (Hello Lactate!!). One effective way to tackle this task would be to run to the top and walk back down as your recovery period. If you want to turn it up a notch knock out some PUPP work at the top and a mobility exercise like a Yogaplex at the bottom before your next run. Use this time to work on getting extra supple by doing some mobility and soft tissue work. A frozen water bottle (Smart Water has a nice shape) works great as an impromptu foam roller.

There you have it! A few ideas to keep you fit during the busy summer travel season. Happy lifting!

Off-Season Recommendations for Track & Field Athletes

Today's post is brought to you by the Goose-Man himself. As a collegiate decathlete, Goose knows a thing or two about off-season dos and don'ts. The principles dictated here can be extrapolated to most any field sport: soccer, lacrosse, football, etc.

Off-Season training for track athletes is a time to give the body a break from all the pounding it took during the season and prepare it for the punishment it’ll face during the upcoming season. This isn’t necessarily the time to work on explosiveness or power, but it is a perfect time to prepare your body to move fast. Here are 4 things you should focus on to reap the most benefits from your off-season training:

- Strength

- Body Awareness

- Posture

- Range of Motion

Strength

Regardless of event (sprints/hurdles/throws/jumps/distance) increases in muscular strength will decrease the chance of injury by preparing your body to deal with the stress of training. However, this doesn’t mean pick up the closest body building magazine and go to town on the hottest new workout for your beach muscles.

You don’t say!

When you run there are two chains, or groupings, of muscles doing work: the posterior chain - calves, hamstrings, glutes, and lower back - and the anterior chain - quads, abs, and hip flexors. The posterior chain muscles are the main movers when running; these muscle produce the force needed to move forward while sprinting and upward while jumping. The anterior chain muscles help stabilize the hips and ensure a smooth power transfer from your legs to the ground.

Field event athletes such as throwers and pole vaulters should also focus on increasing upper body strength. THIS DOES NOT MEAN BICEP CURLS AND TRICEP EXTENSIONS ALL SUMMER!!! Focus on strengthening the shoulders (think overhead pressing variations)and upper back muscles for they will be doing most of the work for throws or vaults.

Body Awareness

Improving your proprioception, the brain’s ability to sense the position and movement of all body parts through space and time, is something not many athletes think about but most would benefit from. Knowing where your body is in relation to it's surrounding is helpful when: performing rotational techniques while throwing, staying inside the lanes when sprinting, controlling your body over hurdles, maneuvering in mid-air when pole vaulting, and running in a tight pack during distance races. It can also help avoid injury by aiding in regulation of body biomechanics/movements while lifting or training.

One of the most efficient ways to improve proprioception is simply by focusing on your own movements. This may sound obvious but the fact is that the ability to focus is a skill, and like every other skill it needs to be practiced! Weight lifting and training should be as much a mental activity as they are a physical activity. Focusing on your movement throughout warm up routines, lifting sessions, and event practices will increase your proprioception to the point you’ll be able to “feel” when you do something wrong.

Posture

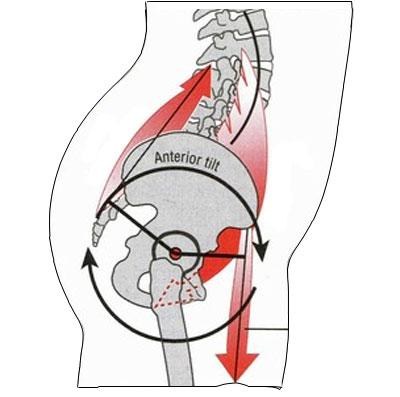

Another aspect of training often forgotten is posture. Distance runners and sprinters must maintain an upright posture with a neutral pelvis in order to maximize the power produced by their anterior chain and maintain a high forward knee drive. Throwers, whether they spin or glide, will have to maintain some type of event specific posture to maximize their efficiency through the power position on each throw. Most track and field athletes who suffer from bad posture exhibit either an excessive anterior pelvic tilt or a protracted shoulder girdle . In layman’s terms they often have an arched lower back or rounded shoulder.

Anterior pelvic tilt can hinder running performance by reducing the levers on the anterior chain muscles by placing the body in an awkward position. Specifically for sprinting, this affects stride length and power by allowing the legs to flail back too far after each step. The further back your legs go the harder it will be to cycle them back forward with a high knee drive, thus hindering the body’s ability to produce forward motion. This may result from weakness in the abdominal muscles, hamstrings, and/or glutes. Tightness in the hip flexors and spinal erectors can also contribute to this. Strengthening your core and anterior chain as well as incorporating flexibility work will help remedy this problem.

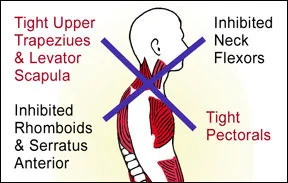

Protracted shoulder girdles will have detrimental effects on the health and performance of overhead athletes like throwers and pole vaulters. Rounded shoulders increase the risk of injury during activities where the elbows are over the shoulders or behind the shoulders such as shot putting, pole vaulting, or throwing the javelin. (note from Kelsey: since the shoulder blade can not glide properly, all kinds of pinching and fraying of tendons and ligaments can occur in the shoulder. Set your blades free!) This can also decrease shoulder range of motion which will hinder performance by decreasing the “pull” you can get on the javelin or shortening the “orbit” on your discus throw. This condition results from weakness in the scapular retractor muscles, like the trapezius and rhomboids, as well as tightness in the pectoralis minor. Strengthening the scapular retractors and diligent use of SMR techniques will help rid you of this problem.

Guuuuurrrrrl, look at his posture!

Range of Motion

Range of motion (ROM) refers to any joint’s ability to move through its full potential of movement in all three planes of motion. In layman’s terms a joint’s ability to move in all the ways it is supposed to move. Optimal range of motion requires both flexibility and stability. Flexibility deals with a muscle/tendon’s ability to stretch and allow limbs to go through the full range of motion of a joint. Stability deals with the muscles surrounding a joint and their ability to keep that joint in place while it moves. (Note from Kelsey: both these components MUST be present for safe and efficient movements.) Improving full body, all joints, ROM can be beneficial to all track athletes. It helps throwers hit a better power position, increases the length of a runner’s stride, improves the technique of hurdlers, and allows jumpers to more easily maneuver their bodies in the air. Please reference the SAPT Blog or YouTube Channel for articles and videos on exercise to help you on your quest for suppleness!

Off-Season Training: Overhead Athletes

Last week, we laid out some general guidelines for athletes heading into their off-seasons. You should read it, if you haven't already. Today, we'll delve into some specifics for overhead athletes (i.e. baseball, softball, javelin, shot put, swimmers (though it seems as if they never have an off-season), etc.). Shoulders are rather complicated and annoyingly fickle joints that can develop irritation easily which is why proper attention MUST be paid to shoulder mechanics and care during the off-season. There is nothing "natural" about throwing a heavy object (or a light one really, really fast) and shoulders can get all kinds of whacky over a long, repetitive season. I'm going to keep it sweet and simple.

1. Restore lost mobility and improve stability

- Hips: they get locked up, especially on athletes that travel a lot during the season (helloooo long bus rides). Restoring mobility will go a long way in preventing hip impingements, angry knees, and allow for freer movements in general. Locked up hips will prevent safe, powerful throws and batting, thus, now is the time, Padawans, to regain what was lost!

- Lats: Usually tighten up on the throwing side and create a lovely posture that flares the rib cage and makes breathing not-so-efficient. Loosen up these bad boys!

- Breathing patterns: Those need to be re-trained (or trained for the first time), too. Breathing affects EVERYTHING. Learning proper breathing mechanics will do a lot to restore mobility (T-spine, shoulder, and hips), increase stability (lower back and abdominal cavity), and create a more efficient athlete (more oxygen with less energy expended to get it). I've written about it before HERE.

- Pecs and biceps: These guys are gunky and fibrotic and nasty. Self-myofacial release is good, finding a good manual therapist would be even better, to help knead that junk out! One caveat: make sure that as you release these two bad boys, you also add stability back into the shoulder. This means activating lower and mid-traps and the rotator cuff muscles to retrain them to work well again. Why? Most likely, the pecs and biceps are doing a LOT of stabilization of the shoulder (which they shouldn't be doing so much) so if you take that away through releasing them, one of two things will happen: 1) injury will occur since there's nothing holding stuff in place, 2) no injury, but the pec and/or bicep will tighten right back up again as your body's way of producing stability. So, mobilize then stabilize!

2. Improve scapula movement and stability

Along the lines of restoring mobility everywhere, the scapula need particular attention in overhead athletes as they are responsible for pain-free, overhead movements. Below is a handy-dandy chart for understanding scapula movements:

Now, over the course of the season, an overhead athlete will often get stuck in downward rotation therefore at in the early off-season (and throughout really) we want to focus on upward rotation of the scapula. Exercises like forearm wallslides are fantastic for this.

Eric Cressey notes that the scapula stabilizers often fatigue more quickly than the rotator cuff muscles. This means the scapula doesn't glide how it should on the rib cage, which leads to a mechanical disadvantage for the rotator cuff muscles, which leads to impingements/pain/unstable shoulders.

As we increase the upward rotation exercises, we want to limit exercises that will pull the athlete back into downward rotation, i.e. holding heavy dumbbells at their sides, farmer walks with the weight at sides, even deadlifts.(whoa now, I'm not saying don't deadlift, but limit the volume on the heavy pulls for a few weeks, and like I said in the last post, training speed work will limit the amount of load yanking down on those blades.) Instead, athletes can lunge or farmer carry in the goblet position (aka, one bell at their chest).

There is more to be said, but let us move on, shall we?

3. Limit med ball work

At SAPT, we back off on aggressive med ball throwing variations for the first couple weeks post season as the athletes have been aggressively rotating all season. Instead, we'll sub in some drills that challenge the vestibular such as single-leg overhead medicine ball taps to the wall. (I don't have a video, sorry.)

Or, stability drills such as this:

If we do give them some low-intensity throws, we'll have them perform one less set on their throwing side than on the non-throwing side.

4. Limit reactive work

We don't usually program a lot of sprint work or jumps the first few weeks. If we do program jumps, we'll mitigate the deceleration component by adding band resistance:

5. Keep intensity on the lower end

As mentioned in the last post, instead of piling on weight, we enjoy utilizing isometric holds, slow negatives, and varying tempos to reap the most benefit from the least amount of weight. We also maintain lower volumes over all with total program.

There you have it! Tips to maximize the off-season and lay a strong, stable foundation for the following season!

Summer = Off Season = TRAINING!!!

Summer is nearly upon us, spring sports are over (or nearly so), school is winding down, and the sun is waking us all up quite a bit earlier. **DEEEEEP BREATH*** I love summer.

Not only is it fantastically warm and I finally sweat profusely during my workouts (contrast that to the winter to where I'm lucky to break a sweat, in my sweat pants...I get cold pretty easily) but it's the off-season for high school sports. I know some of you play your sport year-round in clubs and stuff (see my thoughts on that HERE), but seriously, the summer is a perfect time to start training and getting stronger for next year's season.

So, it's time to hit the weight room, right? Start smashing PRs and moving heavy iron bars around, right? Not so fast, cowboy.

A huge flub athletes commit in the beginning of the off-season is training too hard, too fast. Think about it, you just spent 3, 4, even 5 months in-season with practice after practice, games, and no-so-much lifting. Your body is probably weaker (even if you trained during the in-season, it still isn't PR shattering material) and you've been performing the same, repetitive motions to the point where you've probably developed at least one sort of wacky asymmetry. For overhead athletes, they've been throwing or hitting on the same side, soccer players kick with the same leg, track athletes have been running in the same curve (to the left), and lacrosse players have been whipping their upper bodies around the same direction. Show me an athlete coming out of the season that isn't crooked somewhere (that's the technical term) and I'll show you a One Direction fan that isn't a female teenager. Oh wait, they don't exist. (if you don't know who they are, keep it that way, it isn't worth your time.)

To keep it pretty general, as the two subsequent posts will deal more with specific sport recommendations, here are some thoughts on the first 3-4 weeks of off-season training:

1. Keep the volume down- You've pounded your body all season, high volume work will only stress it out more. Stick to 15-20 reps total of your main lifts (squat, deadlift, bench, etc.) and 24-30 reps of accessory work, total. There should only be 2-4 accessory lifts and 1 main lift per workout.

2. Keep the intensity reasonable-- I'm not advocating lifting 5 lb dumbbells for everything, but again, you've pounded your body for several months, starting at 60-75% of your maxes is not a dumb thing to do. Get some quality, speedy reps in of the main lifts. For you accessory work, move weight that will get your blood flowing, but leaves some gas in the tank (a lot of gas in the tank). If you really want to burn, adding negative reps or isometric holds can increase the intensity without overloading your joints. For example, we like Bulgarian split squats with a :06 negative, or pushups with a :05 isometric hold at the bottom.

3. Take a week away for the barbell-- It's just a week, calm down, but replacing barbell squats with some goblet squats or deadlifts with some swings are excellent ways to give your body a break and still train those movements.

4. Work on tissue quality- Foam roll, use a lacrosse ball, or better yet, go see a manual therapist to dig out the nasty, knotted tissue that resides in your body. Mobility drills for the tight bits and stability drills for the loose bits should be prevalent in your workout. For example: soccer player's hips will be pretty tight and gunky, so that requires some attention to tissue quality of the glutes, quads, and TFL and mobility work. Contrast that to a baseball player's anterior shoulder (front side) of his throwing arm, that this is probably much looser than it should be, so he'll need some stability work to pull his humerus into a more neutral position.

5. Sleep a lot and eat quality food-- I bet both of these have been in short supply over the course of the season, huh? Yes, these two are SUPER important for recovery purposes as well as muscle growth. Shoot for 7-9 hours of sleep per night and load up on the vegetables!

The sole goal of the first couple weeks after the season is to restore the poor, asymmetrical, beaten-up body and allow for some recovery time. Keep the volume and intensity low to moderate, work on tissue quality and mobility as needed, and sleep! Then, and only then, mind you, can you attack the rest of your off-season like the Hulk.

Early Sport Specialization: Why This Needs to Stop (with a capital "S")

Here in northern Virginia, and in other hub-bub places too, it's not uncommon for an athlete to play a sport during the high school season, and then transition straight into the club season (which lasts f-o-r-e-v-e-r), leaving the athlete with maybe 2-3 weeks rest before try-outs for the next year's high school season start. Does this sound familiar? Does this sound healthy? Today we're going to address a growing (alarmingly so) problem with youth athletics: early sport specialization. As a strength coach, I see some messed up kids when it comes to movements, joint integrity, and muscle tissue quality (all = poop) who play year-round sports at young ages (that is, under 16-17 years old). I see year-round volleyball players who can't do a simple medicine ball side throw. Why? Because they spend ALL YEAR moving in the saggital (forward/backward) plane with a little bit of the frontal plane (side to side shuffling, but even that is dominated by their inability to actually move sideways; they tend to fall forward and/or move as if they're running forward, just facing a little bit to the side.) They have limited movement landscape (remember this?) and therefore are limited athletes.

I see young baseball players with chronic elbow or shoulder pain. Why? Because they throw a ball the same way ALL YEAR ROUND. And they're not strong enough to produce the force needed to throw it properly, (because, heaven forbid, they take some time off to actually weight train and get stronger) so they rely on their passive restraints (ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules) to throw.

This topic gets me fired up because I see SO MANY injuries and painful joints in kids who shouldn't have injuries or painful joints. I see kids who can't move like a normal human being because they're locked up and, worse, don't even have the mind-body connection to create movements other than those directly related to their chosen sport.

There's this pervasive myth that if a kid doesn't play year round or get 10,000 hours of practice, then he/she will never be a good athlete. Parents get caught up in chasing scholarships and by golly, if Jonny doesn't play travel ball he'll fall behind, then he won't make varsity, then he won't get into a good college... and on and on. My friends, we need to take a step back and think about what's best for the athlete. Do the aforementioned afflictions sound good to you?

But enough of my opinion, let's look at some hard science to support the Stop-Early-Specialization-Theory.

Playing multiple sports and playing just for the sake of running around like a kid builds a rich, diverse motor landscape, especially during the years before late adolescence. Diversifying the motor landscape, or movement map, or the bag-o-skillz, or whatever you want to call it, is essential to human development and especially valuable to athletes. I'm going to sound like a broken record, but kids need a broad and varied map to:

1. Understand how to move their bodies through space

2. Create and learn new movements

3. Learn how to adapt to their environment

4. Develop better decision making and pattern recognition based on their circumstances (i.e. being able to find the "open" players in a basketball game helps in finding one on the soccer field. )

Matter fact, this really smart fellow, Dr. John DeFirio MD, who is the President of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, Chief of the Division of Sports Medicine and Non-Operative Orthopaedics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Team Physician for the UCLA Department of Intercollegiate Athletics (that's quite the title, eh?) says this:

"With the exception of select sports such as gymnastics in which the elite competitors are very young, the best data we have would suggest that the odds of achieving elite levels with this method [early sport specialization] are exceedingly poor. In fact, some studies indicate that early specialization is less likely to result in success than participating in several sports as a youth, and then specializing at older ages"

And, Dr. DiFiori encourages youth attempt to a variety of sports and activities. He says this allows children to discover sports that they enjoy participating in, and offers them the opportunity to develop a broader array of motor skills. In addition, this may have the added benefit of limiting overuse injury and burnout.

You can read his full article here. The article also notes two studies in which NCAA Division 1 athletes and Olympic athletes were surveyed regarding what they did as children. Guess what? 88% of the NCAA athletes played 2-3 sports as kids, and 70% of them didn't specialize until after age 12. The Olympians also all averaged 2 sports as kids Are you picking up what he's putting down? Specialization doesn't make great athletes, diversification does!

Side bar: Check out Abby McCollum, who played 4 sports for a Division 1 school. The article says that she was recruited last minute... probably because she was such a great all-around athlete that she could play any sport.

Next up: injuries rates.

Dr. Neeru Jayanthi, a sports medicine physician, in conjunction with Loyola University published a few studies using a sample set of 1,026 athletes between ages 8-18 who came into the Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago for either sports physicals or treatment for sports-related injuries. The study ran from 2010 to 2013. Dr. Jayanthi and her collegues recorded 859 injuries, of which 564 of them were overuse injuries (that's well over HALF). Of those 564 injuries, 139 of them were serious injuries concerning stress fractures in the back or limbs, elbow ligaments or injuries to the cartilage. All of these injuries are debilitating and can side line and athlete for 6 months or more. The broad study is reviewed here and a more specific cohort (back injuries, which carry into later in life) is here. I highly recommend reading both as the data are eye opening.

To sum up Dr. Jayahthi and co.'s recommendations on preventing overuse injuries (I took it directly from one of the articles in case you don't have time to read them both):

• If there's pain in a high-risk area such as the lower back, elbow or shoulder, the athlete should take one day off. If pain persists, take one week off. (though I think it should be more)

• If symptoms last longer than two weeks, the athlete should be evaluated by a sports medicine physician. (and go get some strength training! There's a reason that pain is occurring; something is overworking for something else that's NOT working.)

• In racket sports, athletes should evaluate their form and strokes to limit extending their backs regularly by more than a small amount (20 degrees). (this should also apply to any overhead sport like volleyball, baseball, softball, etc.)

• Enroll in a structured injury-prevention program taught by qualified professionals. (hey, like SAPT? Lack of strength is a common denominator among injured athletes.)

• Do not spend more hours per week than your age playing sports. (Younger children are developmentally immature and may be less able to tolerate physical stress.) (10 year-olds don't need 12 hours or soccer! Also check out Dr. Jayahthi's injury prediction formula.)

• Do not spend more than twice as much time playing organized sports as you spend in gym and unorganized play. (Kids, go play tag, get on the playground, play capture the flag, anything; JUST PLAY!)

• Do not specialize in one sport before late adolescence.

• Do not play sports competitively year round. Take a break from competition for one-to-three months each year (not necessarily consecutively).

• Take at least one day off per week from training in sports.

The highlights and comments are mine. Do you see the RISK involved in specializing in a sport early in life? Not only does the risk of injury skyrocket, and the ability to move fluidly and easily plummet, but there's a lot of external pressure on the athlete to perform. Stressed athletes don't perform well. I don't know how many times I've asked my year-round players what they're doing on the weekends, it's always "tournament" or "practice." They have NO LIFE outside of sports. To me, that seems unhealthy and frankly, a recipe for burn-out.

Parents, athletes, and coaches, in light of all this research, I urge you to strongly reconsider year-round playing time for kids under 16 or 17. I urge you to allow athletes time off, to play other sports besides they're favorite, and to just be a kid. I urge you to keep the long-term development of our athletes in mind; do you want to risk a permanent injury, hatred of sport (because of burn out), or development of weird compensations and movement patterns?

Let's build strong, robust athletes that can do well in the short- and long-term instead of pigeon-holing them into a particular sport and limiting their athletic potential.

An Intro to Vision Training

Today’s Post is part 1 of a 3 part series as we tackle vision training. In this first installment, I’m going to try to explain the importance and reasoning for vision training as well as some affects that it can have on just about any task. Make sure you check back later to see the second installment that will deal with more specific scenarios for sports and the third one that will give you some drill and programming scenarios that you can use yourself. Enjoy!

For every action, there is an equal or opposite reaction. In the world of sports, this stays true between competitors. The accuracy and level of this reaction is determined by the perception, strategy and physical ability of the athlete. There are thousands upon thousands of articles written about the later two, but very few on the topic of perception and its role in the way we move and perform.

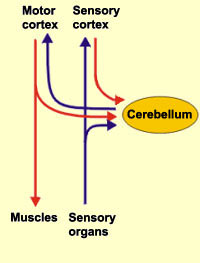

First, let’s define perception and it’s affect on the way we move. Your perceptions consist of the sensory input that your brain collects from your internal and external senses. Essentially, every movement that you have ever performed has been based off of these perceptions. Your brain collects all the different factors of your environmentthrough your sight, hearing, taste, feel, proprioception, smell, vestibular feedback(think balance) and relates them to past experiences. Based on the combination of past experience, current conditions and the task at hand, a movement is chosen and performed. An example of this would be running on wet grass. You seldom consciously think, “I better brace my movements so I don’t frickin’ eat it when I change direction.” You naturally change the length of your stride and adjust the angles appropriately. This is because your brain processed the sensory information: the feel of dampness, the sight of the glistening grass, the proprioceptive feedback of where your legs moving, the vestibular feedback of your body leaning, and the sound of feet skidding on the grass, then reflected on a past experience (probably of biting it on wet grass). It then pieced together a motor program in the cerebellum to be carried out by the body and caused you to run more carefully on the grass.

The outcome of this motor program will be more or less, “recorded” for future reference when you need to complete a similar task. Whether the task is successfully completed or not and how it made you feel, determines if the program will be closely replicated next time.

All of this is relevant to keep in mind when it comes to any type of training, but it encapsulates the whole premise of perceptual training. Perceptual training consists of helping the athlete to identify key elements in their environment to cue them on how to react with the appropriate movement.

Now you can get pretty deep in sport-specific factors that may be important in perception, but for the purpose of this installment, we are only going to look into the visual elements of general sport. For starters, a few key visual factors that will influence all sports are eye dominance, spotting and the vestibular system.

Eye Dominance

Eye dominance plays a key role in how your brain handles site. Just as you have a hand that you prefer to use, you also have an eye that prefer to see from and they may not be the same side. Because both eyes send slightly different portraits of the world, the brain chooses one that is trusts more. In this eye, images may appear clearer, more stable, larger and it has even been suggested to have perceptual processing priority. Some have even hypothesized that it can actually inhibit the sensory information from the non-dominant eye.

There are several types of dominance and honestly, it can all get pretty thick, but the key point to hold onto is that the information gathered through the dominant eye is going to be more credible, processed more quickly and may potentially affect the action taken as compared to if processed primarily through the non-dominant eye. Now there are studies that look into if cross-dominant individuals(right-handed and left-eyed) have an advantages in side-stanced skills like batting due to the closer position of the dominant eye, but they have found no relationship. This is because the stimulus is still well within the focal system of vision, just as it would be with a non-cross-dominant individual.

Now here’s where the shizz-nit gets cool for coaches. Though the athlete may not have an advantage to the dominant side of focal vision, they should theoretically have an advantage in that side’s peripheral vision. This is because the peripheral vision is dependent on the ipsilateral eye, as noted on the above diagram. If we know that one side’s ambient/peripheral vision will have a decreased response time, we can play it to our advantage This could be a game changer in where we position certain athletes.

Another important note to make is that the ambient system is largely controlled by subconscious function. So to take it a step further, you could start performing reaction-type drills within the athlete’s dominant peripheral vision so that the desired response is autonomous(done without thinking). This would help to ensure not only the decreased response time, but more desired responses. This may include drills such as setting a volleyball to a player from their dominant side just within their peripheral vision.

Spotting

No I do not mean the action of helping your bro with his bench press. The spotting I mean is the action of fixating on a particular point during a rotational movement to help reduce dizziness and keep the athlete oriented. You see this when a dancer spins, they will look to one point and keep their eyes set on that point until they are forced to reset. This serves as more of an internal cuing for the vestibular system, but it can be very important in skill acquisition and perception.

As many coaches can note, vision drives movement and wherever the eyes go, the body will follow. This is why appropriate spotting is key in a variety of movements. If the athlete fixates in the wrong position or the wrong time, they could easily throw off their movement, timing and overall performance. An athlete that seems to be over-spotting could be compensating for a vestibular issue. If that’s the case, no amount of technique work will bring that skill to fruition until their vestibular input is restored.

Just the same, there are several cases where the spotting point should be coached to help drive a skill. Think about the individuals who adjust their vision as soon as they hit a golf ball and how it affects their follow through. Or how some baseball players may prematurely look into the field when they hit and negatively affect their swing. You want them to stay fixated on a spot so that the movement can be completed smoothly without alteration of perception.

Vestibular Input

As I mentioned when reviewing spotting, the vestibular system is going to play a vital role in an athlete’s perception. The vestibular system is an internal sensory system that controls the sense of movement and balance, soooo it’s kind of a big deal. It’s largely overlooked in many training programs, especially considering it is the system that will influence EVERYTHING we do. In fact, it is so important the first sensory system to fully develop(at 5 months post conception).

The reason I am including this system in an article on visual training is that the vestibular system will rely heavily on sight for reassurance. It’s always trying to find equilibrium to keep you from falling on your face. Whereas most of the informationused for equilibrium comes from balance organs in the inner ear, it’s estimated that 20% comes from your vision. Consider the fact that most people do not regularly challenge the sensory organs in their ears(rolling around, tumbling, etc.) and yet they are almost ALWAYS using their eyes for feedback, you can see how a compensatory relationship can form.

If an athlete does have a dysfunctional vestibular system, you may see several signs: a loss of mobility when the head is no longer neutral, constant spotting, poor overall balance, etc. The easiest way to rule this out as an issue is to have them stand on one leg with their eyes closed. If they truly suck at this, THEN IT NEEDS TO BE ADDRESSED. Motor control cannot be progressed without the athlete first being able to figure out where they are at in space.

** Fun fact: Regularly working the vestibular system through activities that will work the inner ear organs will help to keep an active brain and grow new nerve cells.

Putting it together

With these factors in mind, I coach can easily address vision training on the field or in the weight room. Knowing an athlete’s eye dominance, when they should be spotting and when their vestibular system is the limiting factor are all HUGE factors of performance. Being able to incorporate the appropriate drills and strategies to match these needs can easily take your athletes to the next level. My next installment will include more sport-specific and task-oriented elements that will help you to take your drills a step further and have your athletes a step ahead of the game.