Part 3: The Preparatory Period a.ka. the Off-Season

The Triathlete Strength Training PrimerPart 3: The Preparatory Period a.k.a. the Off-Season

So far in the series, we’ve provided a brief introduction to periodization and followed that up with the Repetition Maximum Continuum; what it is, how to use it, how to pick a rep range to train with based on whatever particular performance adaptation you are looking to achieve. Some of the concepts in the upcoming posts have been drawn from Joe Friel’s book “The Triathlete’s Training Bible,” a fantastic resource for anyone who lives and breathes endurance sports. This week we’ll dive into what the Preparatory Period looks like for a Triathlete and how to make the most of this crucial period of training.

As we previously touched upon, the Preparatory period is typically the longest period of training and occurs when there are no scheduled competitive events. It occurs following a brief rest period (The nd Transition Period) immediately following the last event of the competitive season. Usually, we refer to the preparatory period as the “Off-Season” and, during this time, we want to focus on a couple of different aspects.

(1) Identify and work to rectify postural issues that have crept in during the competitive season.

All the running, biking, and swimming over the past year took a toll on your body, and the Preparatory Period is when we work to reverse all this damage. Endurance athletes will usually present with incredibly tight hip flexors, quads, calves, and hamstrings. This may result in misalignment of the lumbopelvic hip complex, an excessive anterior pelvic tilt (APT), decreased range of motion (ROM), and sub-optimal force production. On top of that, the sustained forward lean during running paired with countless hours in the saddle bent over the handlebars will almost certainly result in a shoulders-forward kyphotic posture. This kyphosis may not affect your performance during the bike and run leg, but it can certainly lead to injuries during swimming. The misalignment of your shoulder girdle will result in poor gliding of the scapula on the scapulothoracic joint, which can cause the tendons, ligaments and other connective tissues to become frayed, irritated and, ultimately, inflamed.

These postural issues are a result of using the same muscles, in the same abbreviated ranges of motion, to produce movement in a straight line for hours on end. As a result of a long, challenging season, the triathlete is extremely proficient at certain movement patterns (running, biking, swimming), but this comes at a cost; weak muscles in any movement plane or pattern not used during the season. Especially early on in the preparatory period, we want to take the time to train movements in the frontal and transverse planes.

For example, the offseason would be a great time to work on our lateral lunging patterns, KB armbars (KB ARMBARS!), and deadlifts. The lateral lunge is a frontal plane movement that will help train side-to-side stability at our knee and hip joints, while the armbar provides a challenge to scapular stability in the transverse plane, while also strengthening our rotator cuff for a more powerful stroke. Finally, although deadlifts are a sagittal plane movement, they will help us build up hamstring and glute strength that may have been lost during the competitive season.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GRgg0oaq-vQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jTSynq9QmyE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sIdjpVV6N8

(2) Focus on developing strength and power in your prime movers (the big muscles, the money-makers, or the large muscle groups).

We want to be sure we’re taking advantage of the decreased sport-practice time during the preparatory period by focusing on building a strength and power base in the muscle groups used in endurance sport. That means focusing on multi-joint, compound movements such as squats, deadlifts, pull-ups, pushups, and rowing variations. The endurance athlete who is diligent with their off-season weight training will acquire a body capable of withstanding and redistributing the massive forces placed upon it during the running gait, regain any lost mobility, as well as improve their maximal force production, which will lead to increased force production during sub-maximal exercise as well. Consequently, we now have a triathlete who is faster and more powerful with each stroke or stride, better equipped to ride the big ring up a steep hill, and compete at a high level during the season injury-free.

(3) Develop/build dynamic core strength and stability.

This is the optimal time to emphasize developing core strength. During dynamic movement, our core is designed to remain stable and help transfer power throughout our body. For example, swimmers with weak cores will never truly be able to optimize their technique. They lack the control and stability needed to synchronize their upper and lower extremities, and will experience power leaks all over the place. Neglecting your core strength is a sure fire way to negatively impacting your performance, and you’ll have to work twice as hard to travel the same distance.

(4) Concentrate on improving joint stability, muscle coordination, and total body awareness.

Another often under-appreciated benefit that can come from a proper strength training program is improvements in joint stability, muscle coordination, and total body awareness (or proprioception). We can use balance drills, hops, bounds, and stability-focused exercises during the preparatory period in an effort to improve both our performance and resiliency during the competitive season. These improvements will come in handy while riding in a pack during the bike leg, and not to mention the benefit of strong, stable ankles and knees during the run. Taking the time to develop these attributes can be the difference between crossing the finish injury-free, or limping from the stress fracture you received on foot strike #12,375 during your 13. mile run.

I hope the last 800 words have solidified your belief in the need for strength training for the endurance athlete. These are only a small sample of the numerous benefits that result from being diligent in the weight room during your off-season, and they will surely carry over into success on the competitive stage.

Next week we’ll get a little more specific and discuss how to apply periodization to the preparatory period, creating an off-season that is structured to elicit maximum gains in performance. We always want to move from general to specific when it comes to planning our training, and next week I’ll explain exactly what that will look like for the triathlete.

The Triathlete Strength Training Primer

Part 1: An Intro to Periodization - Seeing the Bigger Picture Part 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum Part 3: The Preparatory Period a.ka. the Off-Season Part 4: Off-Season Periodization Part 5: Off-Season Periodization, cont. Part 6: The First Transition Period Part 7: The First Transition Period, cont. Part 8: The Competition Period - In-Season Strength Training Part 9: In-Season Template Part 10: Post- Season Training

Wooden: A Lifetime Of Observations And Reflections On and Off The Court (Book Review)

I was first introduced to this book by a former supervisor who required all of his staff members to read this book to understand his leadership style and as a way to recognize that the little things we do day to day in the workplace add up to make things run smoothly.

I was first introduced to this book by a former supervisor who required all of his staff members to read this book to understand his leadership style and as a way to recognize that the little things we do day to day in the workplace add up to make things run smoothly.

John Wooden, the hall of fame UCLA men’s basketball coach, was able to lead his teams to 10 national championships in 12 seasons with seven of those championships being consecutive. In this book, Coach Wooden, whose wisdom goes far beyond sports, opens up with honest and powerful passages about various aspects of life and leadership. This book is not set up to tell a story or as a biography rather it is an easy read, filled with great short stories and maxims where Wooden explains his philosophy in a manner that is simple, direct, and applicable to anyone. The book is divided into 3 overarching sections. In the first section, “Families, Values, and Virtues,” Coach Wooden discusses his roots and a few of the principles instilled in him and his brothers by their parents and community. The second section, shares his insights on success, achievement, and competition. The third section of this book focused on coaching, teaching, and leading.

I really enjoyed the second part of this book where Wooden explained his “Eight Suggestions for Succeeding,” which included:

- Fear no opponent, respect every opponent

- Remember, it’s the perfection of the smallest details that make big things happen

- Keep in mind the hustle makes up for many a mistake

- Be more interested in character than reputation

- Be quick, but don’t hurry

- Understand that the harder you work, the more luck you will have

- Know that valid self-analysis is crucial for improvement

- Remember that there is no substitution for hard work and careful planning

- Failing to prepare is preparing to fail

This is truly a valuable read for anyone looking to get better at being part of a team, whether that is in the workplace or in sports. People in leadership roles will gain some valuable insights from giving this book a read.

This book is available for sale here.

Top 5 Multi-Sport Athletes of the Last 30 Years

Over the course of my athletic career, I feel like I've played every sport there is. Soccer, gave way to the local swim team in elementary school. Eventually this turned to wrestling, and lacrosse. Finally I found my way to football in high school, and a rugby career that continues to this day

My point of all this is not to list off my athletic resume, but rather showcase how competing in various sports helped me to become a better, rounded athlete. By varying the muscle groups and skill sets I trained, I was able to build weak areas, and create a more encompassing skill set. You don’t have to take my word for this, we are seeing cross over athletes make impacts at the highest level of sports.

Check out my top five multi-sport athletes. Each of these athletes used the skills and experience from their previous sports to propel them to success in their current one.

5)Perry ‘Speedstick’ Baker/Carlin Isles: Many of you may not know who these two gentlemen are, but that will change over the next few years as the 2016 Olympics approach. Carlin Isles grew up playing football, and was a standout at Div 3 Ashland in Ohio. After university he moved to California where he joined the United States sprint team, and narrowly missed out making the 2012 U.S. Olympic team as a 100 meter sprinter. Channeling that disappointment Carlin was discovered by the United States Rugby Sevens team, and since Sevens will be the newest Olympic Sport in 2016, Isles decided to change his focus to becoming an Olympian as a rugby player. In his two years on the national team he has taken the world by storm earning the moniker “The Fastest Man in Rugby.” It’s no surprise that he has world class straight line speed, but his strong background as a football player allows Carlin to also possess a great ability to cut, and avoid defenders all while maintaining top in speed.

If Carlin Isles is the fastest man in rugby, then Perry ‘Speedstick’ Baker is only second by a fraction of a second. Like Isles Baker grew up playing football down in Florida, a state known as a hotbed for football talent. After some time in Canada and the Arena league Perry also found the allure of rugby and Olympic gold too great to pass up. In just a few years, Baker has gone from a club player in Florida to making his debut for the US National team, and he exploded onto rugby's international stage this past weekend in Australia. Baker has a unique blend of size and speed that made him a standout receiver and foreshadows what looks to be a promising rugby career.

4)Dion Sanders: Dion Sanders brought style and flair to the NFL, but while he was locking down receivers for the majority of his career, he was also an important part of the Atlanta Braves championship teams in the 1990’s. Perhaps the most dedicated two-sport athlete of all time, Sanders once played for the Falcons during the day, and played in a World Series game for the Braves that night. Dion had elite level speed that he showcased as a Hall of Fame punt-returner and a more than serviceable outfielder and base stealer.

3)Jimmy Graham: Graham began his career as a basketball player, playing four years for the University of Miami. During a fifth season he took up football for the much celebrated Hurricanes squad. While it was a slow build, he showed enough potential to be picked in the third round of the NFL draft. Within a year he would be an All Pro and setting franchise records for the New Orleans Saints.

Much of Graham’s success is attributed to his ability to make plays in the air on the ball, and his ability to position his body against a defender. These are all skills learned on the hardwood and brought to the gridiron.

2)Russell Wilson: Russell has been a true two sport athlete his entire life. While attending N.C. State he was their starting quarterback and played on the baseball team, and was even drafted by the Colorado Rockies. His football career at N.C. State would come to an early end after his refusal to stop playing minor league baseball in the summer. This led to a year at Wisconsin where he rose the national stage as the Badgers starting quarterback. He made such an impact that Wilson chose the NFL over the MLB. Within two years in the NFL Russell Wilson has become the prototype for the new athletic quarterback. Perhaps his best game changing skill is his ability to slide and get down to the ground safely avoiding the big hits that so many quarterbacks suffer. This is a skill learned from years of sliding while running the base path.

1)Bo Jackson: Bo knows sports. How good was Bo Jackson as an athlete? The New York Yankees drafted him in the 2nd round of the MLB draft but he passed to attend Auburn University on a football scholarship. While in college, Jackson qualified for the NCAA Track & Field National Championships twice. He was a star on the Tigers baseball team, batting .401 for his career, and he won the Heisman Trophy in 1985 an award handed out to college football’s most outstanding player for that season. After college Bo went on to star in the NFL and MLB where he is the only person to be name an All Star in two of the major American Sports.

All of these athletes come from different backgrounds, experienced different coaching systems, and trained different ways. What is consistent between all of them is they were multi-sport athletes who proved you can not only play multiple sports but you can take lessons learned from one and apply to another, and then succeed.

Athlete Highlight: Patrick the Theatrical Athlete

Meet Patrick. He's an accomplished actor, singer (and continues to work on both), and avid Game of Thrones fan (which keeps the conversations lively on the coaching floor).

Oh, how I wish my past self had taken more pictures and videos! He was a totally different kid then. I'll do my best to describe him. Pat started with us at the end of July, 2013.

Pat, a rising sophomore in high school, was (and still is) in drama and also fenced (at the time). He readily admitted that he didn't have much experience with sports and had never weight trained before. During Pat's evaluation, he had a lot of trouble performing a body weight squat (his form was pretty iffy), shook while holding a plank, and struggled mightily with the hops and jumps we do for power assessments. (Especially one-legged hops; single leg anything was Pat's nemesis for the first 6 months at SAPT).

His first few training programs were fairly regressed compared to the typical athlete programs we write. We had him squatting to a bench (which is pretty high, to shorten the range of motion) and with only 15-20lbs. They were definitely not the smoothest squats we'd ever seen. Hip-hinging, aka, deadlifts with a kettlebell were also a tough movement pattern for him to master; he started those with a 20lb kettlebell and stayed between 20-35lbs for about 3-4 months.

He had a lot of low-level drills of just standing on one foot, and when he did start split squats (about 3-4 months in) he utilized the wall for balance. Planks were pretty tough for him, as were most core and upper body exercises too. We elevated his hands pretty high for his pushups (I think we elevated the barbell to around his waist height.)

An outsider looking in might have thought that this kid had way to far to go to actually improve or that he might never be as strong as "regular" athletes (that is the mainstream sports).

But Pat surprised us all.

Pat faithfully came 2x/week, and worked hard every session. Sure, there were some days where he wasn't feeling the best, or he tweaked something, or pulled something (this was a semi-common occurrence during the first few months), or banged into something... He never complained and he consistently did his best to train to the utmost of his ability each day.

Here's a video of Pat's pushups in February of this year:

Not too bad for a kid who started with his hands raised about 6 inches higher than they are in that video.

Pat remained consistent with his training and pretty soon, he was kicking butt and takin' names like the best of them.

Currently he sumo deadlifts around 145lbs, he's squatting with the GCB (giant camber bar) to a LOW box (lower than I squat actually) around the 100lb range. Remember how I said Pat had trouble with jumps? He had a hard time deccelerating and would often lose his balance and fall over. Now, he can knock out a perfect set of one-legged cone hops, forward and to the side. He's performing heidens (it's not Pat in the video, but I don't have one of him heiden-ing. Curses!), heidens with rebounds, and heidens with a medicine ball throw.

And check out his pushups now:

He could have done more, but I told him he only needed to do a few. He can easily hit 25-30 pushups in a session now (on the floor!)

He's lost 25lbs to boot too!

One of my favorite quirks of Pat is his note-taking on his programs. A few months back, I wrote in weighted baby crawls and I indicated that he could use knee pads if he wanted. This was the response:

Clearly, I underestimated Pat. I try not to do so now.

I think it's one thing if the coaches notice these drastic improvements, I mean, that's our job. But, with Pat, OTHER athletes have noticed his work ethic and changes. Three of our D1 athletes have, separately and unprovoked, commented on how impressed they were with Pat's progress. Several other high schoolers have also mentioned or asked about Pat, as in, "Hey, who's that kid? Is he the same one from last year?" or something to that effect. His peers have noticed, rightfully so, his dedication and efforts of the past year-ish; that is pretty darn impressive if you ask me.

Speaking of, Pat has impressed me, and continues to do so, immensely over the past year. I can hardly get over how different he is from last July. He's confident, strong, and his movements patterns have improved by 1000%! Now, you might look at his numbers and think, "That's not so much weight." But you neglect to factor in where Pat started. He started with a 20lb deadlift and is now lifting 145... that's over a 700% increase. Not only that, but he's NEVER lifted before, nor did he have much experience with sports (so he didn't have a rich motor pattern map to begin with, we had to build it in here, which takes a while.)

All of it comes down to consistent training and consistently putting forth his best effort.

To be honest, Pat didn't have much external motivation to keep coming (like a D1 scholarship or something) but HE DID. There was no coach breathing down his neck to improve or the pressure of making a team to entice him to train hard, but HE DID. He doesn't have the freaky natural talent like many athletes (who, if I'm even more honest, often don't train nearly as consistently or as hard as they should because they're talented) but he's improved the MOST out of all my athletes. It's rare to see this dramatic of a change in one athlete in the course of a year, and I am so privileged to be witness to it. Dramatic change for a dramatic guy, I guess. :)

Patrick is why I love my job. I have the amazing blessing of an opportunity to work with kids like him. Kids who may not look that athletic or grand on their first introduction to iron, but through hard work, turn a complete 180 and dominate the weight room. In the strength world, it's an aspiration of many to be the coach of a pro team, or work with professional and highly skilled athletes (and be famous for it).

I'd take one Patrick over 100 pro athletes any day.

Training: Separates the Winners from the Not-Winners

“The more you sweat in training, the less you bleed in battle.”

From what I could gather from a quick interwebz search, this is a quote taken from General George Patton (though swap “training” for “peace,” but the spirit of the quote remains the same.) I strayed across it this morning and it accurately portrays the life of an athlete. There is the competition season and there is the off-season. The off-season should be reserved for rest and recuperation from competition and building up strength for the next round of competition. (Charlie will delve into this in the coming weeks.)

*sigh* Often, though, we see kids (as young as 9 or 10!) competing all. Year. Round. For the ENTIRE YEAR. (For more on this topic, click here.) There are a plethora of problems with this (overuse injuries at young ages, burning out, peaking to early in life, not to mention having zero social life…) but I’ll focus on an aspect that frustrates and saddens the SAPT coaches, one which we are constantly lamenting: total lack of training in favor of competition. Everyone wants to compete but no one wants to train to prepare for competition. (this goes for big boy and girl athletes too. You can’t compete all year-round.)

Competition season often has erratic schedules and can wreck havoc on eating habits, sleep schedules, and the ability to train regularly. That’s expected for a few months, but if an athlete is competing all the time, when will he/she recuperate and grow stronger? How will the joints (and their surrounding tissues) that get abused and overused during the season ever recover? Strength training not only strengthens muscles, but the tendons and ligaments too, which helps prevent overuse injuries because the tissues are more capable of handling the competition performance.

Taking an off-season (a TRUE off season, not playing on a club team) is crucial for long-term athletic success, both in the sport of choice and life. We see a lot of baseball players and volleyball players at SAPT. We’ve definitely seen an increase in the number of players with shoulder/elbow issues and (more the ladies) ACL repair surgeries. And NONE of these kids have even completed high school yet. That’s not supposed to happen. Here’s an article about the retirement of Dr. Frank Jobe, the first surgeon to perform a Tommy John surgery (reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in the elbow). The quote that stuck out to me the most was:

Jobe and John are alarmed by the numbers of 12- to 17-year-olds who are having the operation.

“It’s like an epidemic, and it’s going to grow exponentially,” John said. “These kids are rupturing the ligament. They’re playing year-round baseball.” Justin Verlander, he argued, does not pitch-year round. Why do teenagers?

“The ligament needs rest,” Jobe said.

And that doesn’t just apply to baseball players. It’s an example; apply this across the athletic spectrum to athletes who compete in year-round sports. It’s insane and as a coach, it breaks my heart to see athletes hurt and unable to compete (or function in daily life) in the sport they love. The frustrating aspect? Most of these injuries could be prevented if athletes just strength trained in the off-season with a dedicated focus on getting stronger and building an athletic foundation upon which their specific skills would only flourish (not diminish as some people are wont to think).

Worried the sport specific skills would evaporate over a “long” off-season? Fine, twice a week, work on a few specific skills, for example, lay-ups, volleyball serves, hitting (baseball)… but don’t compete. Get stronger, eat well, sleep well, and I guarantee that the next competition season will be stellar.

Part 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum

Triathlete Strength Training PrimerPart 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum

Hello SAPT blog readers! I trust you all had a great week, and are eager to learn more about strength training and the myriad of benefits it has to offer. We talked about periodization in our last blog post, but how about a quick recap.

Periodization is the manipulation of exercise selection, intensity, and the set/rep scheme throughout the year in order to provide optimal results. We use periodization in order to avoid entering a state of overtraining, take a more intelligent approach to our training methods, and maintain long-term athletic development. The conventional model of periodization involves four distinct phases: the preparatory period, first transition period, competition period, and second transition period.

During each of these phases, we manipulate the intensity of our training loads, by either removing or adding weight to the bar, in order to stress different performance attributes. But, what types of performance attributes are there?

Well, we have strength, for one. Strength is usually thought of in terms of absolute strength, which would be the maximum amount of force a muscle or muscle group can produce. The main objective of a powerlifter is to increase their absolute strength as much as possible in order to lift enormous loads. We can also train for power, which is defined as the amount of work done per unit of time. Power is the rate at which work is being performed, and is especially relevant to athletes that are required to compete for shorts bursts of time. A hockey player or football lineman would be wise to spend a significant amount of time training to improve their power. Last, but not least, we can train for muscular endurance. Obviously, a marathon runner or triathlete aims to improve their endurance above all else. Success in these two sports demands a huge aerobic engine from the athlete.

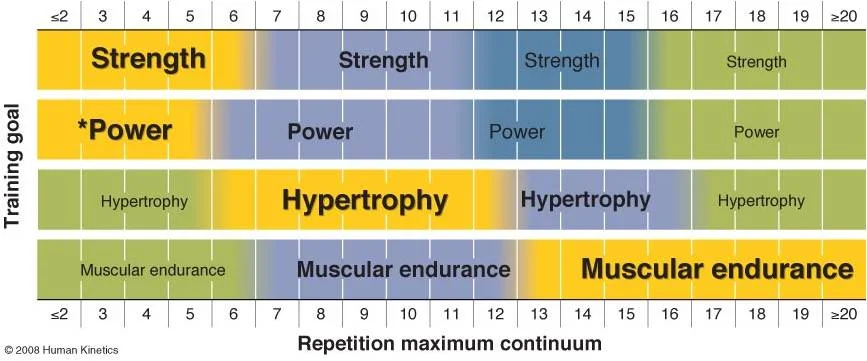

This is where the repetition maximum continuum comes into play. The numbers on the figure to the right order <2 through 20. These refer to the amount of repetitions of a given exercise we are performing with a given weight.

Therefore, the 4 on the figure would refer to a weight that you can lift 4 times, and only 4 times. For example, Jim can perform a back squat with 225 pounds 4 times, but will not be able to lift it for a fifth rep. If he added weight to the bar, he would not be able to complete 4 repetitions. 225 pounds is Jim’s 4-rep max (4RM).

As you can see, these different performance attributes exist on a continuum. Strength is trained to a very high degree when training in the 2 to 5 rep range, but it is also trained slightly when we are lifting lighter weights for sets of 15. As a matter of fact, power follows a similar trend. The continuum tells us it’s important to lift heavy loads when we are focused on training to improve our strength or power, and lighter loads if we are attempting to improve our muscular endurance. We will still see improvements in strength and power when working with these lighter loads, but they won't be as dramatic as when we were working with heavy weights.

You may notice there is a “hypertrophy” range according to this continuum. Traditionally, research has led us to believe that working in the 8-12 rep range has been superior for building size. There is a recent study performed by Brad Schoenfield et al. that seems to dispute this theory.

The researchers took 20 participants who had been weight training for at least 1.5 years previously, and separated them into two groups. One group performed a bodybuilding style program, lifting lighter relative loads for more repetitions (3x10 reps per exercise), while the other group performed a traditional powerlifting style program lifting heavier loads for fewer reps (7x3 reps per exercise). The goal was to examine the effect lifting different relative intensities would have on muscle growth, so the researchers made sure the total amount of weight lifted (volume, or total tonnage) was equal between the groups.

After 8 weeks of weight training, the researchers found that both groups experienced a similar amount of muscle growth (the biceps brachii was measured and both groups achieved about a 13% increase in size), but that the powerlifting group experienced significantly greater improvements when it came to strength. This tells us that there may not be a magical “hypertrophy” range after all. The comparison of two different styles of lifting while accounting for volume implies that muscle growth is largely genetic, and will occur to similar extents if you are following a program based on the principle of progressive overload regardless of the exercise intensity.

One very important takeaway from the study was the physical toll each program had on its participants. The lifters who followed the bodybuilding protocol experienced far less fatigue and injury (2 powerlifters had to drop out due to joint injury), as well as spent much less time in the gym (17 min vs 70 min) then the powerlifting group.

What can we extrapolate from this? Performing a program that utilizes lighter relative loads and a higher rep range will allow us to build muscle size while limiting the amount of stress we are subjecting our joints to, however, we will never see optimal strength gains training this way. Therefore, it is imperative for triathletes to spend some time in the lower rep/higher weight side of the continuum in order to improve strength and power.

Also, we know that our bodies adapt to stress through the S.A.I.D. principle (Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands), and we experience diminished returns as a result of consistent training. This means we will adapt to whatever specific stress we are applying to our body in a specific manner, and, as time goes on, we will see less and less of an improvement if we continue to apply the same stimulus.

This is why periodizing our training is so important! We want to cycle the type of stress we are applying to our body in order to drive performance improvements. By rotating between heavy, moderately heavy, and moderate loads, we’re working to improve different performance elements dictated by the repetition maximum continuum. As triathletes, there will be certain times of the year that we want to focus on improving our muscular endurance, and certain times of the year when we really need to be focusing on strength or power production. The challenge is to determine when to focus on each, and as we continue through the series, I’m going to teach you how to do just that.

Stay tuned for next Thursday’s post, where we will begin to break down the preparatory period and what a triathlete should be focusing on during the off-season.

The Triathlete Strength Training Primer

Part 1: An Intro to Periodization - Seeing the Bigger Picture Part 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum Part 3: The Preparatory Period a.ka. the Off-Season Part 4: Off-Season Periodization Part 5: Off-Season Periodization, cont. Part 6: The First Transition Period Part 7: The First Transition Period, cont. Part 8: The Competition Period - In-Season Strength Training Part 9: In-Season Template Part 10: Post- Season Training