Much Ado About Hanging

It seems almost daily that I get the privilege to explain many of our methods and exercises to our athletes(I love hearing myself talk, especially when I get to get nerdy with some functional anatomy). I understand the reason for questioning many drills, I too wanted to know why people were doing those seemingly silly primal roll variations at one time. But the one question that I am often surprised to hear asked is, “why am I hanging?”

To me the benefits of just simply hanging from a bar are often overlooked, but very clear when broken down. There is a reason you see several individuals instinctively grab onto the top of a squat rack and suspend themselves for a few moments mid-workout. The body often craves the decompressive stimulus it gives. However, due to the simplicity and ease of the movement, many trainers and/or trainees will sometimes dismiss it as a movement worth training.

That is until a couple months ago when Ido Portal(if you don’t know him, look him up) issued the, “hanging challenge” to the movement community. This challenge was beautifully simple and gave extraordinary results to those that followed it. All you had to do was hang from something for an accumulated time of 7 minutes each day for a month. Individuals started posting before and after pictures and sharing their increases in movement quality. Variations started emerging and a unique training tool was brought to the eye of the training realm.

Just like any exercise, there are special considerations that should be taken before implementation. Shoulder pathologies and special demographics should be heavily debated(think overhead athletes) before being exposed to these movements. Progressions should also be kept strict to ensure full results… NO CUTTING! For those that pass the risk-to-reward ratio and follow through with the progressions, the carryover will be well-worth the effort. Keep in mind that there are several variations out there, each with its own benefits, but for this article, we'll only be exploring the passive, active and arching hang.

Just a few contraindications to consider with these movements:

-Shoulder Pathologies… ESPECIALLY IMPINGEMENT

-excessive kyphosis/ lack of passive ROM in shoulder flexion(can be case-by-case)

-Laxity in the humeroulnar or glenohumeral joints

-Spinal Pathologies(mainly for the arching hang)

The Passive Hang

The passive Hang is the platform of which every hanging progression is built, and for good reason. This variation supplies a very unique affect and actually addresses many typical imbalances when employed at the right time. It’s performed by grabbing onto a bar and then just relaxing the rest of the body.

http://youtu.be/iIVg_KK_Uzs

I’m in love with the training effects that this puts on the individual. It provides a great stimulus to the functionality of the rotator cuff while the shoulder is in a decompressed position. Due to the positive relationship to grip activity and rotator cuff activation, the act of grabbing onto the bar should help to reinforce the reflexive stability within the rotator cuff, the oppertunity of doing this in a decompressed position is rare among exercises.

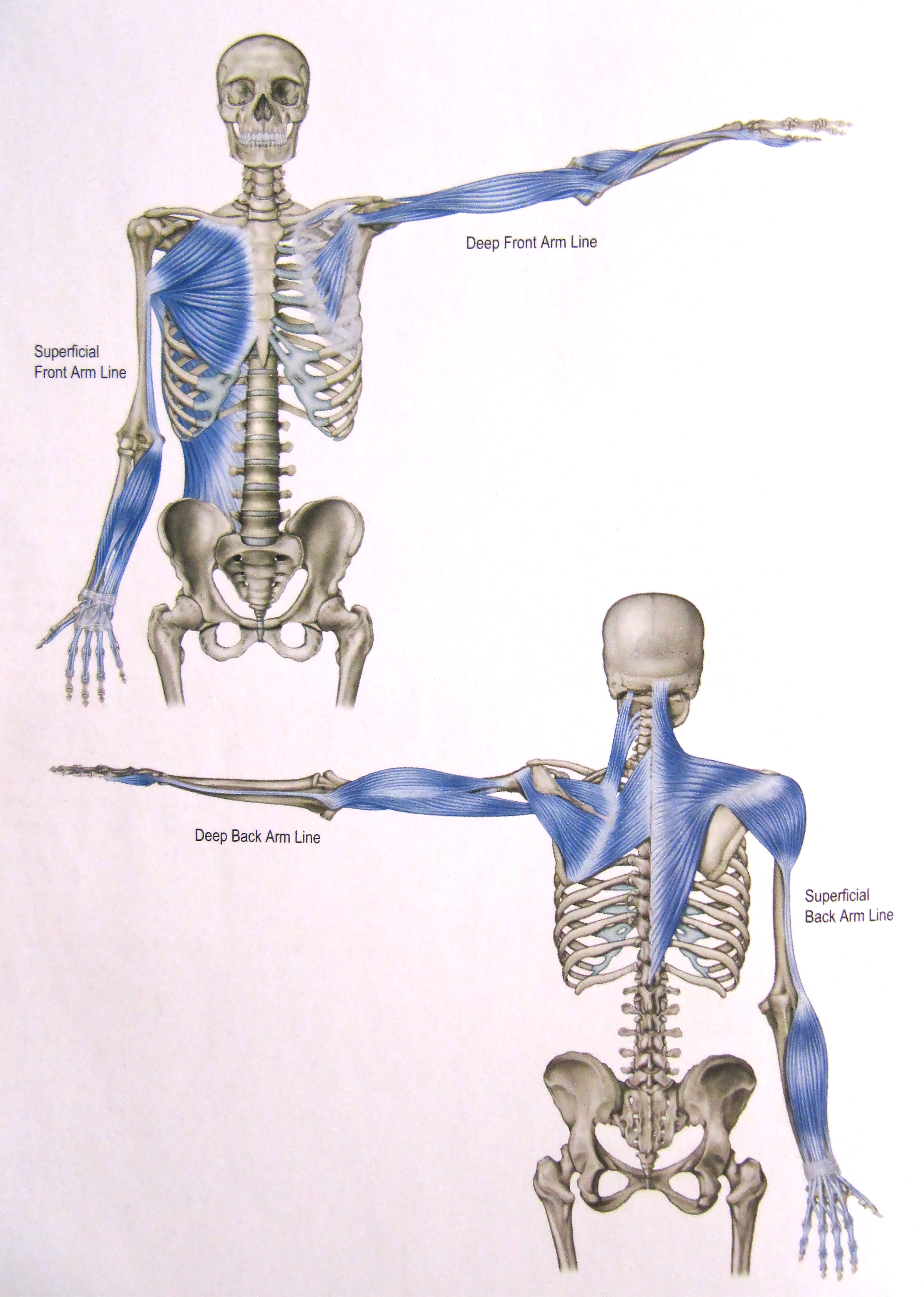

This movement also provides a unique affect to help counteract a fairly common grip compensation. By having the shoulders in flexion, this puts the pec minor in a lengthened position. It's fairly common to see the pec minor compensating for grip mechanisms via the fascia of the arm line. So with the pec minor out of the picture, this gives you an opportunity to train the grip to help break that compensation.

ANDDDD let's not forget the unique stretch that this is putting on the lats, and serratus anterior. This is an area that is often prone to adhesion and can be a limiting factor in many individual's active flexion ROM. Combine this with the forced t-spine extension and lumbar decompression and you've got quite a nifty tool to put peeps back into alignment or even point out unseen balances. It's not unheard of to notice imbalances in an individuals lateral fascial lines when they're hanging. This can be a pretty crucial find for many manual therapists.

**For more lordotic individuals, you will want to consider coaching tucked hips or forward legs to create the decompression.

The Active Hang

I'd like to reiterate that I never move an individual to active hangs without starting them with passive ones first. The volume/amount of time before I progress them on is all dependent on their shoulder mechanics, posture and general conditioning level. The Active Hang is very similar to the passive hang, except now you create tension and pull your shoulders away from your ears.

http://youtu.be/HoE-C85ZlCE

This movement is great for helping more, "trappy" individuals to find a packed position. Many office-laiden individuals have had great results in cleaning up general shoulder wonkiness through this movement. It also has plenty of movement carryover to things such as OH presses, handstands and, the most obvious, pullups. This has actually become one of my favorite progressions to help a lot of clients to be able to do a strict pull up, correctly. It's far too often that I see athletes pull themselves to the bar and somehow seem to lose their neck in the process. For that reason, I've found this to be the best base to teach the correct prime movers of the pull up.

It even has carryover to the deadlift. Yes, this movement can even help your pulling power. By addressing lats and grip strength, it can be a great addition to the end of your deadlifing day. It puts very little strain on your joints, allows your body to decompress after ripping a heavy bar and still creates neural tension. Plus, it leads into the arching hang, which has the most carryover to your pulling power.

The Arching Hang

The Arching Hang is the most advanced variation of the hanging drills within this article, and one of the more advanced variations period. Though it's called an "arching," hang, the majority of the movement is created from the active retraction of the scapula and trying to point the sternum up. So, yes, there should be an arch, but it should not be the main component of the movement. Because of this, it's a more difficult movement to coach and many individuals will take a while to be able to progress to this.

http://youtu.be/C995b3KLXS4

Now before you biomechanists start swinging your goniometers at me, keep in mind that there really isn't that much load on the spine through this extension. In fact, because most of the active extension is occurring along the thoracic spine and since there is very little sheer force to the lower lumbar area, I would argue that this is less taxing on the lumbar spine then the multi-segmental extension test of the sfma. It's for that reason that I personally would only give this movement to individuals who get an FN on the MSE. Plus, just because it's an extension-based movement, doesn't mean it's bad. It means it's just more appropriate for some than others.

The benefits for this movement are fairly vast. Ido calls this skill, "straight-arm pulling strength" and it translates to a plethora of movements. It can help to improve your bench press mechanics by giving you a stronger base to push from. It can also help to keep your upperback tight during your heavy deadlifts. I know for me, heavy turkish get-ups felt like butter after throwing these in for just one wave.

So there they are. 3 basic hanging variations for you to add to your toolbox. Go give them a try with yourself or your clients and if you feel that you want more, I recommend taking a look at Ido's website: http://www.idoportal.com/

Part 5: Off-Season Periodization, cont.

The Triathlete Strength Training PrimerPart 5: Off-Season Periodization, cont.

Last week we dove into the process of setting up a periodized strength training program for the off-season of a triathlete. We introduced Joe Friel’s concept of utilizing both a General and a Specific Preparation Period, and discussed how we can adapt it to our strength training programs. Let’s dig a little deeper down the rabbit hole that is sport performance training.

The General Preparation Phase

Your last race of the season was 2-4 weeks ago… You did well, but missed your goal time by 3 minutes. You’re endurance was on point, but you just didn’t have the leg strength to cruise up the hills or keep a strong pace during the last couple of miles in the run. You know you can do better and after reading the past 4 parts of this series, you’re convinced taking an intelligent approach to strength and conditioning is what has been holding you back. It’s time to get serious this off-season.

Part 4 introduced the Gen. Prep. Period, and gave a framework on how to approach training during this time. We want to be focus on developing muscular strength and anaerobic power, preferably in muscle groups that we use while cycling, running, and swimming.

Swimming

- The unique aspect of the swim portion is the fact that you can use your arms to propel you through the water. A triathlete with a strong pull can easily navigate the swim while saving their legs for upcoming bike and run legs. Picking weighted pull-ups and row variations will help us build a strong shoulder girdle and upper back that is crucial to developing a strong freestyle. A pull-up motion is very similar to the pull in freestyle, so this exercise will have tons of carry-over to performance.

Cycling

- The forward lean during the saddle-position in cycling shifts most of the work to our hamstring and quadriceps. This prods us to pick knee-dominant lower body movements. You may be tempted to choose a Bulgarian Split Squat with a “short” stance to really nail the quads one at a time in order to be bike-specific, but remember, this is the General Preparation phase, and we really want to focus on building as much strength as possible. A better choice would be the high-bar back squat or the front squat. These options allow for heavier loads to be used, and therefore more gains in absolute strength, while also requiring a more up-right torso angle and less glute involvement.

Running

- The front squat and high-bar back squat would also be great choices to build leg strength specific to running. This improves the value of these exercises as we can use them in order to build leg strength for both sports. Running involves more hip extension then cycling does however, so we want to also pick a movement that will help us build strength in our hip extensors (hamstring and glutes). Both deadlifts and back-elevated glute bridges would serve well in this department. Once we reach the Special Preparation Period, we’ll want to move the bulk of our strength work towards single-leg variations in increase specificity and build more run-specific strength.

Below is a sample week of strength-focused training for the General Preparation Period of a triathlete.

The Special Preparation Phase

Next lets take a look at what a week of training would look like during the “Special Preparation Period.” Remember, we are starting to get more sport-specific during this phase and our conditioning focus will shift from increasing our anaerobic power to increasing our anaerobic capacity.

Wrapping Up

As we get closer and closer to our season, we want to shift our training focus away from developing general adaptations and become more methodical and specific. We need to start programming exercises that will have more direct carryover to our sport, in this case, swimming, biking, and running. The Special Prep week that is posted above would occur pretty early on in that phase. As we near the end of this phase, we would want to shift our conditioning focus to developing aerobic fitness and our strength work would be more focused on slow-twitch hypertrophy. This means utilizing methods such as HICT Step-Ups or the 2-0-2 Tempo Method for strength work.

Always remember, each and every training program you write should be tailored towards the individual athlete. The corrective drills in the example weeks above are specific to that particular individual’s goals and needs, so a program suited for you may look drastically different in terms of exercise selection.

As always, thanks for reading and be sure to post and questions or comments in the section below. Stay tuned for Part 6 next week and keep Tri-ing!!

The Triathlete Strength Training Primer

Part 1: An Intro to Periodization - Seeing the Bigger Picture Part 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum Part 3: The Preparatory Period a.ka. the Off-Season Part 4: Off-Season Periodization Part 5: Off-Season Periodization, cont. Part 6: The First Transition Period Part 7: The First Transition Period, cont. Part 8: The Competition Period - In-Season Strength Training Part 9: In-Season Template Part 10: Post- Season Training

An Inside Look At The Pro Agility Test For Athletes

It’s football month here on the SAPT blogosphere and because testing is vital, we’ve decided to take a look at a few of the common tests that football players of all levels will likely face at combines or clinics. In this first installment we will take a look at the Pro Agility Shuttle run (AKA the 5-10-5) which is a foundational test used by coaches to evaluate a player’s ability to accelerate, decelerate, and change direction quickly and efficiently. In a game, football plays are constantly evolving and the ability of a player to stop, shift their weight, and accelerate in the opposite direction is very valuable.

The pro agility drill is a fairly simple test to administer because the only equipment needed is open space, cones, and a stop watch. The event is set up with three cones in a line, each separated by 5 yards. To execute this drill, the athlete will begin by straddling the middle cone with the other cones at their left and right. Timing starts on the athlete’s first movement from the center cone. Once started the athlete must sprint 5 yards to the right, sprint 10 yards to the farthest cone, and then sprint 5 yards through the center cone which represents the finish line. This test also has the option to be performed going to the left side. Click here to see video of the pro agility test performed at a very high speed

Probably the largest area that is ripe for improvement in this test is the person’s turning technique, which if sloppy, can cost valuable time along with possible injury. To be the most efficient with each turn, a runner must get low as they make the turn in order to maintain balance and slow down without toppling over. This position also allows the person to keep their center of gravity atop their legs which will be used to propel them to the next cone. An easy scenario to envision this would be to imagine a tractor trailer attempting to make a high speed turn and then, compare that to a high end sports car like a Lamborghini making that same turn at a high rate of speed. Barring any bad driving skills the sports car with its lower center of gravity will have more success in these turns. Would you rather be the big rig or the Lambo?

Another area where time can easily be lost is just shy of the finish line where some testers will try to finish with 3 or 4 really large steps as opposed to keeping their current stride pattern and slowing after the finish line. Correcting this is typically what is asked of an athlete when they are told to “run through the finish line.” Shown below is chart showing the normative scores for NCAA D1 athletes from a variety of sports. Check back next week as we discuss the broad jump and ways to unlock a few extra inches.

Table: Hoffman, Jay. Norms for Fitness, Performance, and Health. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2006. Print.

5 Not-So-Common Tips on Finding and Cultivating a Mentorship

When pursuing excellence in a particular discipline - athletics, business, academics, music, “life” in general, you name it - finding and procuring a mentor to guide and sharpen you is not a nice-to-have. It’s a must-have.

I’m not going to delve into the why of the matter, however, as I believe you already know the why.

Besides, if the one and only Gandalf had mentors during his time on Middle-earth, then you and I both need them during our time on Regular-earth. The equation is simple.

Now, while the why may be simple, the how is a different matter entirely.

Many individuals recognize the supreme value of mentorship, but often feel stymied in their attempts to actually make it happen. This could be due to a variety of factors: lack of direction (“where do I even begin?”), fear of being turned down, or, quite frankly, laziness.

In my own life, while walking down the path of attempting to identify suitable mentors and enter into fruitful relationships with them, I’ve made no small number of mistakes. Fortunately, these mistakes have birthed many valuable lessons and insights which have enabled me to, eventually, experience some pretty amazing and invaluable mentorships that I am forever grateful for.

Here are a few fundamental principles and essential ground rules that I’ve picked up during my own personal journey.

1. It’s not necessary to find the highest-level expert in the field

Say what?

This statement may catch you by surprise. After all, why wouldn’t you want an unrivaled expert in your field of interest to be the very one who personally teaches you, nurtures you, guides you, challenges you during the process of honing a specific skill set or discipline?

There are many answers to that question, but one of the most important is this: they may not be the best teacher.

[As an aside: while mentor and teacher are not synonymous, all mentors are teachers to some degree, which is why I raise this point.]

The interesting thing about true masters of a specific domain, is that they’ve been so deeply intertwined with the subject for so long that the fundamentals, the critical information that a beginner must learn during the early stages of skill acquisition, have become so deeply internalized that these basic principles are now seamlessly integrated into their actions without even having to think about them.

As Josh Waitzkin aptly put it, the foundational steps are no longer consciously considered, but lived.

“Very strong chess players will rarely speak of the fundamentals, but these beacons are the building blocks of their mastery. Similarly, a great pianist or violinist does not think about individual notes, but hits them all perfectly in a virtuoso performance. In fact, thinking about a “C” while playing Beethoven’s 5th Symphony could be a real hitch because the flow might be lost.”

~Josh Waitzkin (8-time national chess champion and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black belt)

What’s the point to all that? Well, this can make it very difficult for a well-seasoned maven to dig back down into the depths of their mind, in order to extricate, section out, and then teach the basal yet essential principles they learned long ago but now employ unconsciously.

It’s not that they can’t teach or mentor a student in the ways of their craft, but they may not be able to do so as well as others in the field. There’s a large difference knowing and teaching. For example, I’m sure many of you can recall a prior physics or math teacher, or sport instructor, who may have been brilliant within their craft but yet you had a difficult time learning while under their tutelage.

This concept even carries over to reading books. As I’ve sought to improve my chess game, I’ve actually found it quite helpful to not exclusively buy books written by Grandmasters (the highest achievable title in chess). You would think that a Grandmaster would be the best person to learn chess from, but, for reasons mentioned above, this isn’t always the case. For example, I have found treasure troves of insight within the works of Jeremy Silman, an International Master (one step below Grandmaster) who has built a strong reputation for his ability to teach beginners, despite the very fact that he is not a Grandmaster. It’s his knowledge of the game, in concert with his gift of teaching, that makes him shine, not the standalone fact that he’s a highly ranked chess player.

Ergo, when you seek mentorship from someone: they don’t have to be the absolute best; in fact, it may very well be optimal if they are not. You don’t need to head straight to the tip-top of the skill pyramid. Often you can find someone who is still extremely proficient (way more so than you), who will be able to instruct you and augment your learning process in a manner much more effective than even the “best” within that discipline.

Find a great teacher. Not necessarily the unparalleled expert.

2. Mentorship doesn’t have to be a formal, official arrangement

Probably one of the worst things you could do upon discovering a prospective mentor is to call them up and ask, “Hey, do you want to mentor me?” This is tantamount to you calling and saying, “Hey, do you want to take on an unpaid, part-time job?”

While I’d be remiss to assert that no successful mentorship has ever been started this way, this doesn’t change the fact that it’s still an odd way of asking. Even if they do say yes, it puts them in the awkward position of feeling like they need to plan out regimented meetings and send out a syllabus or something.

Here’s one of the most important things to know about mentors: a mentor is anyone you can learn from, who can impart wisdom upon you, who can directly or indirectly help to guide the decisions you make and actions you take. He or she can be a family member, a coworker, someone you already interact with quite regularly, or perhaps someone you only speak to on a quarterly basis. It also helps to ensure this individual is not a fool.

Some of my best and most fruitful experiences with mentors have risen out of informal relationships. From time to time, usually without it being planned in advance, they’ll provide me with a gem of seminal insight, or a particularly profound nugget of wisdom, which permanently alters my course for the better.

Should some mentorships be formal? Absolutely. But more often than not - at least during the beginning stages - it’s best to just let mentorship “happen.”

Don’t be the weirdo who comes right out and asks for it. That would be like my clumsy, ill-fated attempts to date a few women I fancied back in high school and college; rather than allowing our relationship to nurture and grow for a bit, and giving them subtle yet clear context clues of my interest, I just came straight out and asked, “Hey, would you like to be my girlfriend?”

Yeah, that rarely ended well.

3. Take a break and do something else together

Talk about things and do random crap that don’t at all pertain to your usual subject of study. Enjoy sarcastic banter and making fun of one another; grab a beer together; play a video game or chess; go on a bike ride; travel or go cliff jumping; play a sport; go see a movie or simply take a walk around town.

This accomplishes a couple things. First, it will help you connect to one another as human beings. It’s not rocket science: the more you get to know them, laugh together, and share a broad spectrum of experiences, the more you’ll be able to dismantle any personal barriers that you - often unintentionally - assemble and put up between you and other people. Within the context of mentorship, these personal barriers serve nothing other than to ultimately impede the learning process that could otherwise flourish unhindered between the two of you.

Second, and I can’t overstate this enough: it will nurture your creative processes in a profound way. Oddly enough, remaining singularly fixated on only the subject of study is not the optimal approach, even if your only goal is to learn that specific subject!

Steve Jobs knew this very fact, and summed it up well in an interview with Wired back in 1996:

“A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. They don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions, without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better designs we will have.”

~Steve Jobs

Broaden your experiences, not just as an individual but also with your mentor. It may seem like a waste of time, especially if you’re someone who becomes intensely obsessive with that one thing you’re trying to master or accomplish, but it will be more than worth it.

4. Remember they are not infallible beings

When you highly esteem someone, heavily admire their work, and love receiving advice from them, it can be easy to arrive at the subconscious conclusion that this person is without error or character flaws, to elevate them to something of a deity and hang on every word they speak or write as if it were inerrent ideology.

Then, when they inevitably crack (or shatter) the standard of perfection you’ve set for them - say, by making a mistake, or by slighting you in some way - it’s as if the ground crumbles beneath your very feet as the world comes crashing down around you. You either become pissed off at them and write off anything they ever said as fraudulent and worthless, or stew in despair and disbelief because the person who you believed would never mess up or upset you, just did.

Like anything in this world, when you make a good thing into an ultimate thing, it becomes an idol that will eventually enslave you, let you down, or both.

Nobody is perfect, and the privilege of being mentored by someone you highly respect is always an extremely delicate balance of trusting their wisdom and yet continually remembering they are nothing more than human; at the end of the day, they are prone to the very same pitfalls and character flaws as you. If they screw up, or irritate you in some way, just relax. Take a few deep breaths, forgive them, get over it, and get back on course.

5. Your personal network: don’t ignore the power of it, and don’t neglect to broaden it

While the maxim “it’s not what you know, but who you know” may be a cliche, that doesn’t make it untrue.

Everything from crucial internships, to the job I currently hold and love, to incredible opportunities I’ve experienced, to being connected with some crazy awesome and widely-respected mentors, have all been fruit I was able to pluck and enjoy as a result of seeds planted long ago in the form of interpersonal relationships.

This is one of the many reasons it’s imperative not only to refrain from burning bridges, but also to form as many as possible. You just never know how a friend, a prior coworker, or even an acquaintance, may be able to help connect you with a reputable individual who would otherwise be all but inaccessible. You can never have a network that is broad enough.

In fact - and I’m sure I speak for my fellow introverts when I say this - keeping in mind the above sentence is one of the primary tonics that keeps me going during formal social gatherings and conventions. You know, those dreaded events which require one to endure that insufferable affliction otherwise known as small talk. I would rather swallow a live hand grenade than spend a few hours small talking with strangers who I’ll probably never see again. But again, you really never know what may come as a result of it - they may be able to help you, or you may be able to assist them, in remarkable ways.

While by no means exhaustive, I hope the above points provide a small window of clarity into the often cloudy and undefined realm of mentorships.

Agree? Disagree? I’d be curious to hear anything you’ve found helpful, be it with the actual finding of mentors, or nurturing the relationship once it’s already formed.

Rate Of Force Development Part 2: Training and Increasing RFD

Last post, I went over some of the terms and definitions of rate of force development (RFD). I also mentioned motor units (MU) and if, at this point, you have no clue what I’m talking about, go back and read it. It’s right here. Why should you care about increasing your rate of force development? Answer: power sports (which is every sport to some degree) are dependent upon the ability to produce high levels of force at any given moment, like running away from a T-Rex.

There are two main ways research and experience backs up to train RFD: explosive strength training (Newton et al. Med. Sciences Sports Exer. 1999) and maximal load training, i.e. picking up heavy stuff. (McBride et al, J. Strength and Conditioning Research 2002). It should be noted that most of the research has been done with isolated muscles/movements (it’s a lot easier to test the quadriceps muscle in a leg extension machine than the various muscle groups in a deadlift) and so it can be a little tricky to apply to real life. However, where science has holes, the experience of coaches fills the gap!

First: force = mass x acceleration Keep this in mind…

Explosive training (speed work) is taking a sub-max load (say, 50% of your one rep max) and moving it as fast as possible, with good form obviously, for 1-3 reps per set. That’s key- as fast as possible. Those high threshold motor units, the ones that produce the most force, are recruited to move that weight quickly by contracting quickly. Even though the load is light, the acceleration is high. By challenging your system to move loads supa fast (actual speed measurement), we can increase the force production by increasing the acceleration part of the equation. This is one way to train and increase RFD, by working on the "speed" (or "velocity" for the nerds) part of the equation.

Typically at SAPT, we program 1-3 reps for 6-8 sets with a strict :45-:60 rest period. Why the rest parameters? We want to keep the nervous system “primed” and if the rest period is too long, we lose a bit of that ability to send rapid signals to the muscles.

Maximal load training, aka picking up some freakin’ heavy weight, will typically be above 90% of your one rep max, likewise we keep the rep range between 1 and 3 (mainly because form can turn to utter poo very quickly under heavy loads if the volume is too high). This untilizes the other part of the force equation, mass. If the acceleration is low, the mass has to be high in order to create a high force production. Once again, neural drive is increased and those high threshold MU’s are activated. The threat of being crushed beneath a heavy bar can do that.

Bottom line: As the an athlete's RFD increases –> the recruitment threshold of the more powerful motor units decreases –> more force is produced sooner in the movement –> heavier weights can be moved/athlete becomes more explosive in sport movements.

Think back on poor lifter B from last post who had a really low RFD during his 400lb deadlift attempt. Being the determined young man that he is, he trained intelligently to increase if RFD through practicing speed deadlifts (to get the bar off the floor faster) and maximal training, (to challenge the high threshold units to fire). Pretty soon, instead of taking 3 seconds to even get the bar off the floor, it only takes 1 second of effort and instead fo straining for 5 seconds just to get the bar to his knees, he’s able to accelerate through the pull and get it to lock out in just under 4 seconds. Success!

For sake of the blog post, we could assume he always had the capability of producing enough force to pull 400lbs, but could produce it fast enough before his body pooped out. Now, with his new and improved RFD, 400lbs flies up like it’s nothin.’

Another thing to keep in mind is the torque-angle relationship during the movement. Right… what?

All that means is the torque on the joints will change depending on their angles throughout the movement, thus affecting the amount of force the muscles surrounding those joints must produce. For example, typically* the initial pull off the floor in a deadlift will be harder than the last 1-2 inches before locking out due to the angle of the hip and knees (at the bottom, the glutes are in a stretched position which makes contracting a little tougher than at the top when they’re closer to their resting length.) Same concept applies to the bench press, typically** the first 1-2 inches off the chest are more difficult than the last 1-2 inches at lockout. The implication of all this being the muscles will have different force-production demands (and the capability to meet those demands) throughout the exercise.

Knowing this, we can train through the “easier” angles and still impose a decent stimulus to keep those higher threshold motor units firing the whole time. How?

With chains and bands! Yay!

Aside from looking totally awesome, chains provided added resistance during the “easier” portions of the exercise to encourage (read: compel) muscles to maintain a high force output throughout the movement. Watch Conrad, The Boss, deadlift with chains:

At the bottom, when the torque-angle relationship is less favorable, the weight is the lightest and as he pulls up, the weight increases as glutes must maintain a high level of force output to complete the deadlift. No lazy glutes up in hea’! Bands produce a similar effect. Check out the smashingly informative reverse band bench post Steve wrote here.

There are other ways and other aspects to discuss (like the fore-velocity curve... but that is a tale for another day!), but quite frankly, this blog post is reaching saga-like proportions so I’m going to cut it here. And remember kids:

*unless your name is Kelsey Reed and you have a torso 6 inches long… but can’t lock the pull out.

** unless your arms crazy long.

4 Drills to Clean Up a Hinge Pattern

Drills are an awesome and totally underutilized tool within most exercise programs. It's not hard to fall into the mindset of always needing to get stronger within a movement rather than just getting better at it through practice. This is CRUCIAL for people just beginning their strength training program as their initial gains are all based off of just learning how to do things, and thus can be expedited through the extra practice.

Hearing the term, "drill" also changes the mindset of the client. When you address a simple movement as an exercise, often times the client will be more aggressive in execution as they try to, "feel the burn" or fight you to let them go heavier. But when introducing a drill, it's often understood that the purpose is to learn the finer points of the movements and focus on technique. It then becomes immensely easier to progress the movement, blow through the noob gains or even clean up technique in more advanced lifters.

I personally find that the general population has the hardest time getting down their hinge pattern. This is most likely attuned to picking up things the wrong way on a daily basis combined with the whole factor of glute amnesia. It's for this reason that I've started using hinge drill variations in almost everyone's programs to help with their deadlift without having to worry about fatiguing the movement. I find that it helps with clients of all levels and experience.

The following are some of the most common drills you'll see us use at SAPT in the order of less to more advanced. Keep in mind that for people starting off, they are best paired with glute activation drills to help build stability in the posterior chain during the pattern.

Knees Against Bench Dowel Rod Hinge Drill

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2lHamIPidrc

This drill is awesome for all levels of lifters. To perform it, set up with your knees about an inch or two(everyone will be different) from a bench and hold a dowel rod against the back of your head, thoracic spine, and sacrum. Once set, push your hips back as you allow your knees to touch the bench. Go as far back as you can without letting you knees come off the bench or letting the dowel rod come off your head, point on your t-spine or sacrum. Come back out of the hinge and do not let your knees leave the bench until you are almost to lockout. Keep your feet relaxed and planted the entire time. Ideally one hand will be in the space of your lordotic curve to help give better feedback of if your back starts to round. If the knees come off the bench, you've sacrificed hip extension for knee extension. If the dowel rod leaves you, then you've lost your neutral spine. ONLY GO AS FAR AS YOU CAN WHILE MEETING THESE REQUIREMENTS.

This drill has become a staple for beginners at SAPT and I have found it to reinforce a correct hinge pattern faster than any other corrective. As previously stated, I often like to combine it with floor-based glute activation exercises to help give the client more posterior chain stability and allow them to hinge further back. Also, for more quad-dominant individuals, I will abuse this exercise during their rest periods. It's not uncommon for you to see 10 sets of 10 to be performed throughout the session.

This is an(especially) appropriate drill for anyone who has the following issues:

- Locks out knees before hips

- Has trouble keeping a neutral spine

- Has a poopy ASLR and is not yet ready for deadlifts(especially when combined with the next on the list)

- Poor posterior weight shift ability

Band Resisted Quadruped Rock

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VrRzZypg-cM

This drill looks odd at first(especially when performed by Waldo), but it can be pretty powerful when used correctly. Due to the knees being unable to translate during the movement, it shifts the entire focus to the hip extension and using the hips as drivers for propulsion. It's also one of the easiest movements to coach considering it's built off of a developmental pattern.

You can use several different types of harness, I chose this one for the video as it's the most popular among gyms. Just make sure for this types that the chain goes through your legs rather than behind. With it set up as shown, it'll give fairly personal feedback for when the pelvis starts to tuck or if spinal flexion starts to appear(especially for guys).

To perform, start as shown in quadruped position with a band hooked to your harness. Keep a tall posture and imagine you're pushing the ground behind you as you rock forward. The rock back. Done. due to it's simplicity and easiness, I like to program sets of 10-20.

This is an(especially) appropriate drill for anyone who has the following issues:

- Locks out knees before hips

- Loads the back rather than the hips

- Has a poopy ASLR and is unready for deadlifts(especially when combined with the previous drill)

- Poor body awareness

- Has lower-leg dysfunction that is affecting traditional hinge movements

Band-Resisted Hinge ISO

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZPnyLULK9Cg

This drill is a little more advanced than the previous ones. We tend to introduce this to individuals who have already been exposed to kettlebell deadlifts, but may be having some trouble with them. Or we may just want a tension exercise and to get the glutes more involved. The reasons can span on since it's been found to be such an effective movement for progressing deadlifts.

Due to your body reflexively tightening your posterior chain to protect you from falling back, you'll be hard pressed to find an exercise that causes a more effective glute contraction. Because of that, the uses for this drill are vast. But what it also does: teaches correct load/tension in the bottom of a deadlift, reinforces position, gives an opportunity to teach proper bracing mechanics, gives a safe variation for introducing isometric work into deadlifting.

To perform this, you need to have already established competency in the first drill. If someone has trouble keeping a neutral spine or cannot physically get into a proper hinge position, this IS NOT for them. To set up attach band or cable from the ground a few feet behind you, to your hip crease. With a kettlebell either in deadlift position OR a bit in front of you, grab on to it and set your back as if you're about to lift. Then hinge back into the band. It will try to pull you further back, causing your glutes to automatically turn on to prevent you from falling. Between the added weight of the bell and the tension you've created, you will feel your strong and stable position. You will know a client has reached the appropriate spot once their shoulder are over their feet.

Again, I want to reiterate that the bell can be in front of you rather than in deadlift position. Most people starting off will need it to be in front and that's ok. I've yet to see a correlation between the position of the bell for this drill and poor carryover to deadlifting. The main component is the main position of the hips and torso. You can even see my toes start to elevate, meaning that I probably should've had it a little further in front.

This can be tricky to coach, but it's been extremely effective. Just make sure that: the arms are long, the back is flat, the shoulders end up over the feet in a hinge position and the client stays tight. I like to use the cue, "attach yourself to the bell then pry your hips into position so that the band can't move you." I also make them hold a brace in this position to help prep them for once they lift heavy.

This drill is appropriate for anyone who has the following issues:

- Poor set up

- Looses tension on initiating the pull

- Has trouble loading the hips

- Poor bracing

Band Resisted KB Deadlift

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0uHFeR55Su0

This drill is just a dynamic variation of the previous one. I find that many clients will have a great first rep, then will get, "quaddy" when lowering the weight, putting them in poor position at the bottom and killing the smooth transition to the next rep. This drill helps to keep them honest and remind them to load the hips through both portions of the lift.

You'll notice that I start the movement from the top and allow the band to assist in pulling me into position. This is because some people may have trouble finding the initial pull position at the bottom with the band constantly pulling them back(the same reason why I said some people will want the KB in front of them for the ISO). Starting from the top diminishes that issue so long as the 5lb plate is there. to guide them where to put the bell. The band helps to establish a RNT(reflexive neuromuscular training) effect which will keep the glutes involved through the entirety of the lift.

This drill is appropriate for anyone who has the following issues:

- sagital knee translation during lift

- poor eccentric phase

- hamstring dominance