“Core” training is always a popular topic in the fitness field, but it’s usually as misunderstood as Bill Cosby after a root canal (or in general). Popular fitness divas, whose names must not be said, like to show you the best new crunch variation to hit your “Abz” or your “Luv Handles” and try to pawn it off as core training. Not to burst your bubble, but these aren’t real core exercises. These are usually just isolation exercises that happen to target a muscle or two of the torso.

“But my abs are part of my core”

True they can be considered part of your core, but they aren’t necessarily your core. Your core is a unit of muscles that work together to stabilize parts of your body during movement. Truth be told, it is very hard to define what the core actually is or consists of. Some people define it as, “from your head to your toes and everything in between.” Some people say it’s everything that attaches your pelvis to your rib cage. Coach Charlie had a great post a few weeks ago about how almost any exercise can work your core, but he points out that there’s a difference between working and targeting. In order for us to be on the same page on targeting the core, I feel that I should share my definition.

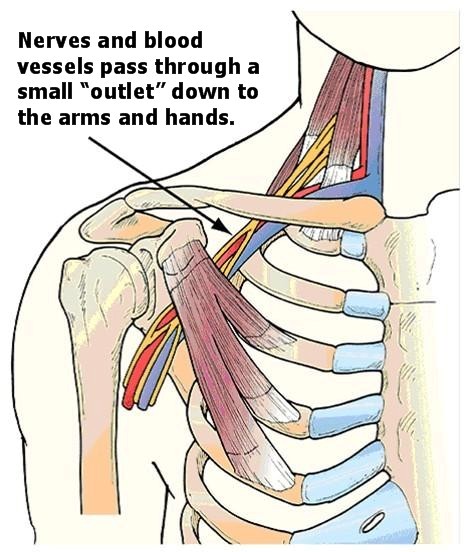

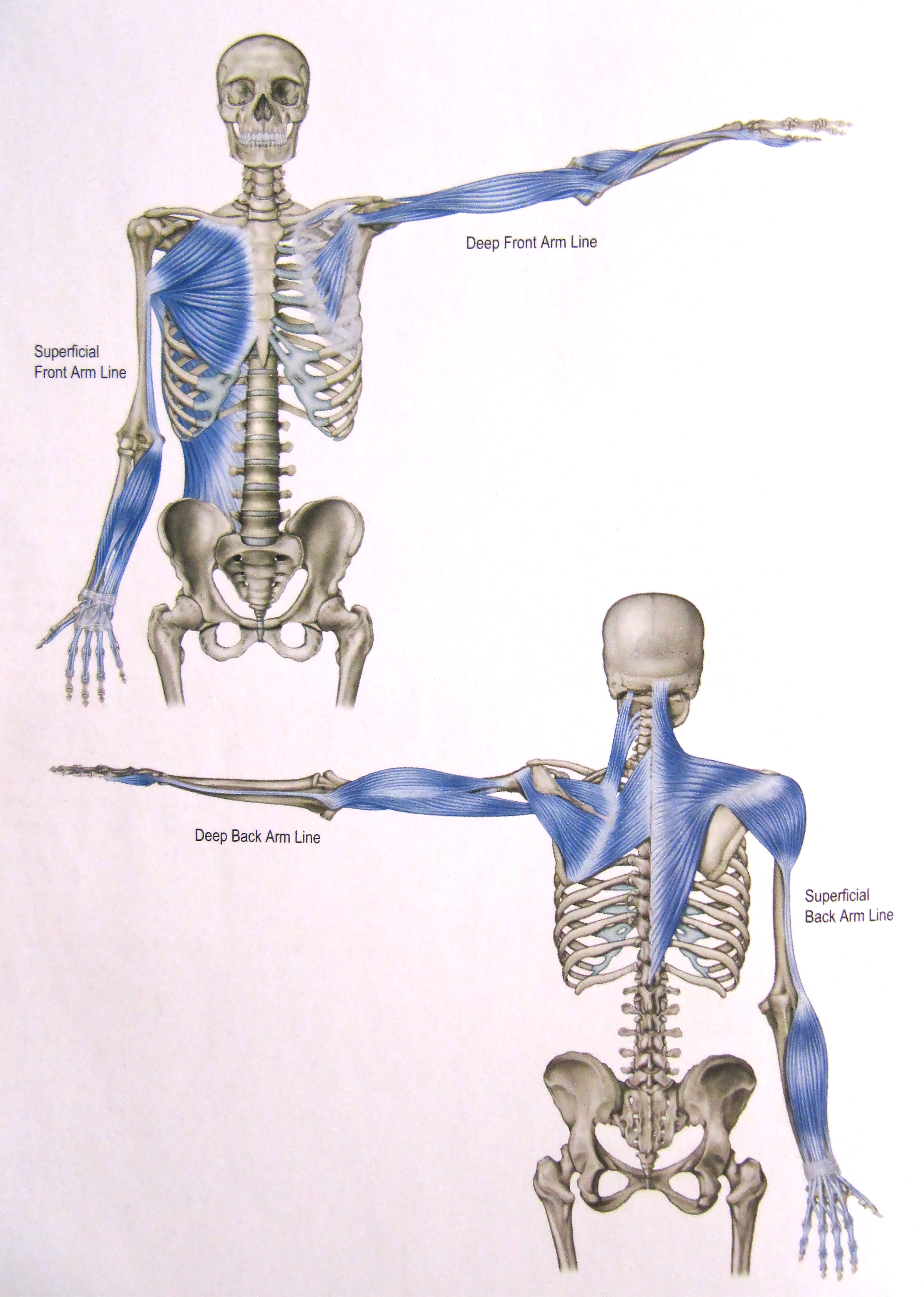

I define the core as the group of muscles that create a stable base for movement, allowing your limbs to accelerate, decelerate and transmit force through your body or an implement. In this way, the core becomes very relative to the activity or movement. It allows for an easier understanding of how the stabilizing area should be trained for maximal transfer to specific activities. Put simply, the muscles that define your core depend on the movement you're doing.

For Example: Watch above, you’ll notice the actual force generation comes from the hips and is transferred to the bat. You’ll also notice that the torso itself stays locked down as it’s rotated by the hips until his follow-through. The torso stays stable so that the force from the hips can be transferred effectively into the bat. This is the rotary stability (ability to stabilize rotation) function of the core. And for this movement, I’d broadly define the core muscles as the muscles that make the rotary stability for this movement possible: hip extensors/stabilizers, oblique slings, rectus abdominis, rotares/multifidi, scapular stabilizers and so on. By training these muscles to be active as a unit in rotary stability type movements, I should have the most carryover to his swing and a very effective core exercise.

Trying to work these muscles in isolated groupings would be akin to doing team building exercises by yourself. Isolation work has it’s time and place, but it rarely yields the results that most of us strive for. It misplaces much of your effort into one element, rewarding you with a false sense of satisfaction because you can, “feel the burn.” Just because you feel that muscle burning, does not mean you’re going to receive your desired training adaptation.

If you’re trying to look good naked, and you’re limiting your training stress to just one isolated muscle at a time, you might as well be doing HIIT with a shake weight. You need to put the stress over a large quantity of tissue to help elicit a much more potent metabolic stressor. The more fibers that are put under tension, the more calories that are burned and hormones that are released to elicit a training response. There's no better way to do this than through compound core movements.

If you’re trying to become harder to kill, training muscles in isolation has little carryover to movement, ESPECIALLY with core work. Your muscles don’t work in isolation when they are stabilizing your spine, allowing you to run, throw, punch, jump, kick or swing that bat. You need to focus on the sequencing of these muscles and their ability to stabilize and transmit forces effectively. This will allow you to run faster, punch harder, and protect that lower back better.

The main functions of the core can be grossly broken down into rotary stability, anti-extension and anti-flexion (lateral and linear) exercises as these strategies are usually how the muscles fight for stability. I have found that using my definition of the core, in cohesion with these functions, is extremely useful for being objective about what will carry over best for my athletes. It helps me pick the best variation of movement for particular sports and positions. I have also found that the variations that fit this bill, seem to be the most challenging and metabolically demanding exercises to hit your mid section. But, I’ll let you be the judge, here are my 12 favorites sorted from hardest to easiest and by category,

Anti Extension:

Dragon Flags

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Q7l07Pu0HA

My training partner once slapped me in the gut after I did a set of these, his hand is still in a cast. This is probably the most advanced and grueling anti-extension exercise I know other than the Front Lever series. Dragon flags are a great way to include eccentric loading (lengthening phase) of the anterior chain. Just make sure to do them nice and slooooow, while keeping your body straight from the bottoms of your ribs to your toes. Admittedly, this one mainly focuses on the abz and may look like a crunch's foreign cousin, but it's a popular variation for gymnastic style training and strengthens your anterior core very quickly.

Turtle Rolls

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E4y3dQSBCEA

Warning: Side effects of turtle rolling may include muscle soreness, strength gains, slight gas, shortness of breath and a sick feeling of satisfaction. This is another great anti-extension exercise that focuses on the anterior chain as a whole unit. Though the limbs do not move, there is still a transmission of force as your partner pulls you up and down. Maintaining this position at a slow tempo is extremely challenging, but can have huge mojo for any grapplers in the crowd.

Bodysaw Planks

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RE5xLOZqfMQ

Do you grow tired of normal planks? If you have sliders or a suspension trainer, give these babies a whirl. This is an anti-extension exercise that moves the vector of strain throughout the range of motion, causing different fibers of the anterior core to be stressed more than they would in other anti-extension exercises.

Rotary Stability

Landmine Rotations

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=upUKXfawkyo

This is a more advanced, standing, rotary stability exercise that will force you to create tension from the ground up. As you can tell from our intern, Mike, the goal is to keep your pelvis square with your hips and not allow any rotation from the spine as you move the barbell from side to side. A little weight can go a long way if you have longer limbs, so really focus on staying tight and increasing it slowly. I’m talking, “grind a pebble into a pearl with you butt cheeks,” tight.

Hard Rolls

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8jbQyoeO47k

There has never been a more straightforward name for an exercise. These are freaking hard when you first try them. You want to squeeze your opposite elbow and knee together while trying to touch the walls of the room with the other limbs. You’ll then pick your head up and look to the direction that you’re rolling. NO KICKING OR PUSHING OFF, USE ONLY YOUR INTERNAL TENSION FROM THE ELBOW AND KNEE! It helps to squeeze a basketball or something in between your elbow and knee when first starting out. This is what you see our athlete, Red, doing above. The decreased ROM will make it much easier to recruit the desired fibers. Once you can master this, dump the ball and go elbow-to-knee.

Wide Stance Pallof Press

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bA7hdjs-Tno

This one will help get those buns of steel while still hitting your abz and obliques. There are many different variations of the pallof exercise, I just really happen to like the wide-stance for limiting adductor recruitment (they like to help people cheat). Once it becomes easy, you can start moving on to the chop and lift version to help you kick more butt with your Bo staff.

Deadbug with Stability Ball Squeeze

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eakh9HKEtvQ

This exercise can be deceivingly brutal due to the constant tension placed into the ball. You’ll quickly feel it working and learn how to recruit the right fibers to resist rotary forces and lumbar extension. It’s a great place to begin as you progress to the harder variations listed above.

Anti-Flexion (Mainly laterally)

Overhead Pallof Press

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWjM-V7PstA

Rotary stability at the bottom with some nice lateral flexion-resistance at the top. Though you can load up the fireman carry way more, I would say this one is more difficult and more directly challenges the lateral system when paused at the top. People will literally go weak in the knees and start hiking through the hip on this, so be tight, stay stable, square and reach for the stars!... Then hold that reach for infinity!

Fireman Carry

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFZe5AgFaeg

Put something heavy on one shoulder and walk. It’s simple and a great way to resist lateral flexion while building up the muscles of your side. There’s a reason Firemen are strong.

2 Point Single Arm Bent-Over Row

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kY3H8RMrVlE

This is a great anti-forward-flexion exercise that also has a hint of rotary stability. It’s surprising the amount you will feel this in your anterior core when breathing correctly, despite being in a hinge dominant position. You’ll notice this is the only anti-forward-flexion exercise that I’ve really listed. I find that the back extension pattern is already worked enough in main movements like deadlift and squat variations and rarely needs to be targeted with extra work.

Suitcase Carry

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cNvc6_jieaw

There’s no exercise more applied to everyday life than picking up something heavy and carrying it. Doing one side at a time will help you to resist flexing to one side or falling over. Though this one is simpler than the others, don’t underestimate its usefulness in a training program.

My Favorite All Around:

Renegade Row

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q6LPtLxMuv8

This hits a little bit of each of the core functions. I consider these much more of a core exercise than an actual row. The limiting factor is never the rowing strength. It’s always the ability to stabilize on the 3 points of contact, so don’t be an egomaniac and use typical rowing weights. Also, for the love of all that is Holy, please don’t look like a hungry cow when you perform them. I see people attempt them all the time, letting their hips sag way too low while their head nears the ground, like they’re about to graze on some grass. It makes me want to bang my head against the wall until that form makes sense. Keep the hips level with the shoulders and square with the ground as you row. It’s that simple.

Try throwing a few of these variations into your next routine. Remember to progress yourself into them as many are harder than they look. After a few weeks, you'll be punching sharks and turning heads like never before!