Breathing Drills

The foundation of our work with close to 100% of the population we work with begins with correcting breathing patterns. In a nutshell, here is why…

The foundation of our work with close to 100% of the population we work with begins with correcting breathing patterns. In a nutshell, here is why:

- Dramatic improvement in movement patterns

- Fewer injuries

- Better recovery (between intense bouts and sessions)

- More bulletproof and awesome

- Sets the stage for building to athletic potential

When you or your child begin a training program at Strength & Performance Training, the first step is going through our advanced, unique, and cutting-edge evaluation. From the results of that evaluation, we begin the program design process.

As with any evaluation process, the results impact the pathways that come thereafter. In the case of SAPT, their are varying levels of pathways. Each with their own sub-paths. Over our many years of working with athletes at every level and from every walk of life, we have been able to determine the pathways that lead to the greatest progress in the most efficient possible route.

Our first pathway, the one that is always prioritized as both foundational and necessary in all programs, is that of breathing patterns and drills.

Life Support

The human body really is a marvel. When given the proper conditions, it is capable of high-performance, the likes of which we have yet to see fully realized. While on the other end of the spectrum, given the “proper” conditions, the body is capable of adjusting and functioning in extremely unfavorable conditions. Great athletes can even thrive when everything about their lifestyle and training would indicate otherwise.

The body can adjust to anything that does not actually kill it. We somehow manage to eat completely manufactured food-like products and still manage to think, write, walk. Humans have adapted to a lifestyle of sitting, when we were clearly designed for low-level ambulatory activity at most times. The examples can go on endlessly.

As these adjustments occur, we generally tend to think everything is on the up-and-up in our bodies. Why walk, run, or bike from place to place when we can sit, relatively relaxed, in a motorized vehicle that quickly zips us from A to B? Sure, it is comfortable. But, when that sitting is complimented by another 8+ hours of sitting at school or work with an extra 3 hours reclined on the couch it starts to accumulate and effect your body negatively. The results - that you may only notice over time - include: poor circulation, atrophied gluteal muscles, low back pain, sciatica, rounded shoulders, forward head posture. All of which result in big time postural problems, predisposition to injury, and a myriad of physical and psychological problems.

While it has become more generally accepted by the public that sitting = bad and moving = good, there is a lot more to this. The science of human performance is just that: Science. The research coming out every year is staggering and the knowledge that has developed just in the last 5-years is unbelievable.

At SAPT, we only have human performance specialists on staff. Not hobbyists. Professionals. As such, our charge is to ensure that the programs and, ultimately, value we deliver to our clients must stand at the forefront of the industry.

Since we’re diving right into science, let’s take a look back at the simple example of sitting = bad and moving = good. Okay, I agree. But, let’s take that deeper. Let’s be a little smarter about this and ask some more questions:

We know that the common mal-alignments in the body ultimately stem from poor pelvic balance and that is, in fact, causing the postural asymmetries.

But what causes this poor pelvic balance in the first place? Traditionally, we’ve chalked it up to an increasingly sedentary environment - too much sitting, not enough moving. Even for children. In fact this problem first develops in children, all children.

Let’s go deeper still. There is actually something else going on besides our chair bound, screen driven environment. It just so happens that if you look very deep, like inside your body, you will discover that the muscle responsible for respiration, the diaphragm, is actually itself asymmetrical! In fact, the thorax is packed with asymmetrical situations: the heart sets on one side, the liver on the other to adjust the diaphragm is divided into two domes (on the right and left sides) one dome is smaller and weaker than the other. This sets off a precipitation of events. All of which ultimately influence our athletic performance, efficiency, injury patterns and more.

Posture

Let’s break this down a bit further. It’s important to grasp this point. If you can grasp this, then you will understand our methods: All kinds of important parts of the body attach and interact with the diaphragm. Since, by our bodies’ design, one side of the diaphragm is stronger than the other and that means that certain compensatory patterns always develop. Always. If you are a human you have these patterns.

The diaphragm is stronger on the right side, this ultimately means that we favor (and overwork) the right side of the body. While the left side becomes weakened and inefficient. Similar to having a dominant hand, the right side of the diaphragm is everyone’s dominant side.

After understanding this as fact, we can see the commonplace asymmetries develop: one shoulder higher than the other, the rib cage set at predictable angles from right to left and front to back, the pelvis rotated predictably.

Injury Potential and Predictability

Alright, we’re getting back on solid footing. The by-design asymmetry of our diaphragm causes the postural asymmetries that cause, over time, injury. This is another fact.

How many times has a well meaning coach had an athlete statically stretch chronically tight hamstrings? Do they ever regain the proper ROM? Nope. But, those tight hamstrings are actually indicative of a risk for injury that points to pelvic misalignment and, you guessed it, points then towards diaphragm and thorax corrections that MUST occur before high performance can ever be achieved.

Another common example: How many times has a pitching coach focused their injury prevention program to address only the throwing side? Their thought being that they need to strengthen and protect the side of the body that gets worked all the time. WRONG. Good gracious that’s just layering on the problems. The body needs to be balanced out for high performance.

Sub-Optimal Performance

Let’s continue to talk about the pitching coach who runs a one sided arm care program. Hey, it kind of makes sense. You throw with one arm, why wouldn’t focus on strengthening the musculature on just that side?

Because over time you create many layers of dysfunction. These layers can be very hard to peel back in older, trained athletes. These layers will inevitably limit the lengths of their careers (from a physical standpoint).

Never, ever layer strength on top of dysfunction. The potential for injury skyrockets (that’s my opinion) and it becomes very difficult to make the foundational corrections (to backtrack).

The result? The athlete has now gotten “stronger” and tighter and more imbalanced in the pursuit of increased performance.

What should the approach have been? Fix the imbalances first, prioritize this as essential to performance, then and only then, begin to strengthen.

Respiration

When respiration isn’t occurring efficiently, an athlete’s ability to recover between bouts of training (or plays in a game) will be suboptimal. Potentially leading to injury, compromised decision making (think ability to read a developing play), lost points, or a Loss.

Gait

We’ve established that the diaphragm will cause poor pelvic balance. But what does that mean for gait?

“Walking and breathing are the foundations of movement and prerequisites for efficient, forceful, non-compensatory squatting, lunging, running, sprinting, leaping, hopping, or jumping ONLY WHEN three influential inputs are engaged: proprioception, referencing, and grounding.” [PRI coursework]

Pulled muscles, ligament tears, rolled ankles can all be traced back to a pelvis, and thus, breathing problems.

Turns out, that tilted and rotated pelvis can be a real problem!

How many great (or on their way to great) athletic careers have been stopped in their tracks by an injury?

How to fix: Zone of Apposition

Moving forward with the understanding that breathing really is the key to life, we have to ask: how do you fix this?

There is something called the Zone of Apposition (ZOA) and this is the area where the diaphragm and ribcage overlap each other. We want to maximize this overlap through proper ribcage positioning.

Here’s the good news: train the ribcage to be in the proper position and now those imbalances start to clear up. The benefits include:

- Better ROM at all joints

- Better recovery for bouts of work

- Less compensatory patterns throughout the body

Now we can work on performance!

How we use/integrate breathing drills to achieve performance improvements

Ground based:

Against gravity —> Static

Against gravity —> dynamic & sub-max: These drills are any movement in which we can take the opportunity to work on proper alignment of the ZOA and respiration while moving our bodies with or without load. A standing dumbbell shoulder press is an excellent example of a sub-maximal exercise that can be executed with consideration to breathing (or not).

Against gravity —> dynamic & max: again examples include actual lifts but this time at maximal effort or maximal speed. The deadlift is a good example. Taking the opportunity to set the ZOA is what ultimately will fire the core, protect the spine, and make for a more productive lift. And, YES, it IS possible to be very strong and execute max effort with perfect form!

What the athlete gets as a result:

- Better movement patterns (without forcing it)

- Fewer injuries

- Better recovery (between intense bouts and sessions)

- More bulletproof and awesome

It seems that to truly get what we want from our bodies, we need to first take care of some of the deepest considerations: diet, breath, mindset pop out to me.

Deadlift Fine Tuning: The Setup

Here is a little before and after troubleshooting I did on an athlete's deadlift this evening. Check it out:

Common Beginner Mistakes - Part 3

Part 3 of the "Common Beginner Mistakes" series is underway! Like all the great series' out there (Game of Thrones, Breaking Bad, Star Wars...), it's important that you check out each and every single one. Take a look back at Part 1 and Part 2. I'm sure you'll find a hidden gem or two in there that will help you make better progress in the weight room. As you may know, I'm a creature of habit. I tend to order the same meal from Taco Bell (6 crunch tacos), dry my body off in the same sequence after taking a shower (I know... I'm weird), and I always choose the color blue while playing Settlers of Catan. With that, let's check out a couple of videos of incredible feats of strength.

Mistake #7 - Program Hopping

"Programs Hoppers" are a severe annoyance to all experienced strength and conditioning coaches out. They typically suffer from a mild case of ADD, commitment issues, and a severe lack of gains. These individuals can often be seen at your local Crossfit gym, never performing the same workout twice. These people need a lesson in the mechanisms of musculoskeletal adaptation. Mentioned in part 2, a major principle behind strength training is called the SAID principle. This states that you body will form Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands. In other words, your body will adapt to the stimulus that you apply to it, HOWEVER, it's critically important that you apply the stimulus for a sufficient period of time. If you're constantly changing the stimulus, the training effect will be negligible, and your body won't experience enough of the same stress to adapt and grow stronger.

This is why most of the established training programs are designed in blocks. The exercise selection inside of a single block is typically static, and each block typically lasts 3-4 weeks. This way your body has enough time to experience and adapt to the method of training. Now, I'm not advocating doing the same exact thing for 3 weeks straight. Another important principle of strength training is termed the Repeated Bout Effect. This principle states that as you apply a stimulus and your body recovers and adapts to it, the same stimulus will not elicit an equal amount of adaptation. Your body experiences a point of diminishing returns, and this is the reason we apply progressive overload and increase the weight on the bar over time. In this way, we're applying a slightly greater stimulus, but maintaining the movement and allowing our body to adapt to greater and greater amounts of the same stress, and grow stronger because of it. Here at SAPT, we program our clients in 4 week blocks, increasing volume over time, which in turn elicits progressive and consistent adaptation.

Mistake #8 - Sticking to the Same Program Too Long

Now, this may seem a bit contradictory to our previous point, but hear me out. I touched briefly on the Repeated Bout Effect above, and this point of diminishing returns applies to whole strength programs/methods of training as well. Eventually, if you continue to do the same thing over and over and over again, you'll reach a point where you just aren't making measurable amounts of progress. Once this occurs, you need to change the stimulus that you're applying to your body. This doesn't mean do 1 week of 5/3/1, 2 weeks of the Cube Method, and follow it us with another week of Starting Strength. You need to stick to a program to actually elicit the adaptation you are trying to achieve, and then mix it up and change the program once you've gotten all that you can from it.

This is a tricky concept, but in reality, you should be grateful for these training principles! They allow you to gain valuable training experience. All these programs are created using different training philosophies. They utilize different methods of manipulating volume over time to elicit strength gains. We're all unique human beings, and, because of this, we respond to stimuli in different ways and to different degrees. Some people respond better to high frequency training with low to moderate intensity loads, while others adapt more efficiently to lower volume, high intensity training plans. You may not respond to a training program in the same exact manner as your best friend, and you also may not adapt as well the second time you perform a program. As you become more and more experience in strength training, you'll discover what works best for you. You'll discover the style of training that meshes with your personality, lifestyle, and preferences, and, with a little bit of patience, you'll develop a system of eliciting strength gains progressively.

Powerlifting Training for Sports

You must clearly understand the difference between basic training and special physical preparation. [SPP] is different for everybody; one beats up on a tire with a sledgehammer, another does figure eights with a kettlebell, and someone incline presses. Basic training is roughly the same in all sports and aims to increase general strength and muscle mass. Powerlifting was born as a competition in exercises everybody does.

— Nikolay Vitkevich

Don't you want to know more?

I wrote a guest post over at Concentric Brain you can read it HERE.

Rate of Force Development: What It Is and Why You Should Care

No, sorry, this is not a post on how to become a Jedi by increasing your rate of using the Force. Shucks.

The Rate of Force Development (RFD) we're going to talk about is that of muscles and is *kinda* important (read: essential to athletic performance). Today's post will enlighten you as to what RFD is and why one should pay attention to it. Next post will be how to train to increase RFD. So grab something delightful to munch on (preferably something that enhances brain function, like berries.) Caveat: There is a lot of information and other stuff that I’m not putting into this post, sorry, this is just a basic overview of why RFD is important for everyone.

What is RFD?

It is a measurement of how quickly one can reach peak levels of force output. Or to put it another way, it’s the time it takes a muscle(s) to produce maximum amount of force.

For example, a successful shot put throw results when the shot putter can exert the most force, preferably maximal, upon the shot in order to launch it as far as humanly possible. She has a window of less than a second to produce that high force from when she initiates the push to when it's released from her hand. Therefore, it is imperative that the shot putter possess a high rate of force development.

Where does RFD come from?

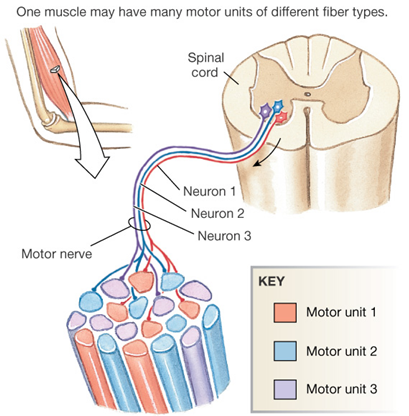

Well, let me introduce you to a little somethin’ called a motor unit. Motor units (MU) are a motor neuron (the nerve from your brain) and all the muscle fibers it enervates. It can be anywhere from a 1:10 (neuron:fiber) ratio for say eyeball muscles, which have to produce very fine, accurate movements. Or 1:100 ratio of say a quad muscle which produce large, global movements.

There are two main types of MUs: low threshold and high threshold. The low threshold units produce less force per stimulus than the high units. For example, a low unit would be found in the postural muscles as they are always “on” producing low levels of force to maintain posture. A high unit would be in the glutes, to produce enough force to swing a heavy bell or a baseball bat (even though the bat is light, the batter has to move that thing supa fast in order to smack a home run).

Also note the different stimuli required for the different units: small posture adjustments vs. a powerful hip movement. A low stimulus activates low threshold units and a high stimulus activates the high units.

Now, MUs are not exclusively low or high; MUs throughout the body are more like a ladder, low MUS at the bottom, with each successive rung being a higher threshold MU than the one below. And, like a ladder, you can just all of the sudden find yourself at the top of the ladder without having to climb the lower rungs. Unless of course, you’re a cat:

High MUs rarely (if ever) activate without the lower MUs activating first. So, the rate of force development is dependent upon how quickly the lower rungs of the MU ladder can be turned on to reach the highest threshold units (which produce the most force per contraction)… Not only that, but all those units working together produce more force than just the higher ones by themselves, so it's a good thing that the lower ones must activate too. The muscular force produced is the sum of all the motor units.

Why Care About RFD?

Since those higher threshold units won’t be active until the lower ones are on, force production will remain low until the higher ones can get their rears in gear, therefore, going up the MU ladder faster will result in more force produced sooner in any sort of movement.

Let’s take the example of two lifters, A and B. Both are capable of producing enough force to deadlift 400lbs. However, lifter A has a higher RFD than lifter B. Lifter A can produce enough force to get the bar off the ground in about 2 seconds and lock out (complete the lift) in about 3-4 seconds. Lifter B takes 3 seconds to get the bar off the floor and another 5 to get it near his knees. For those who don't know, a deadlift should be roughly 4-5 seconds TOTAL (typically, most people's muscles give out around then if the lift hasn't been completed). B-Man is going to fail the lift before he gets that bar to lock out and will hate deadlifting forever. Bummer.

Or, utilizing a Harry Potter for my analogy for this post, it is analogous to the rate of spell development; how quickly and how powerfully a wizard's spell is performed. In a duel, the faster and more forceful wizard will win. For example, when Professor Snape totally pwns Gilderoy Lockhart:

Hence, if one wants to get stronger, increasing the rate of force development is essential! Moving heavy weights is good (and high RFD helps with that as we saw with Lifters A and B from above); moving heavy weights FAST is even better when it comes to stimulating protein synthesis aka: muscle building. Possessing a high RFD is vital in order to move those bad boys quickly.

Next post, we’ll delve into training methods that can help increase the RFD so you won’t be these guys and skip deadlifting because your rate of force development is less than stellar…

Why Train In-Season?: Strength and Power Gains

Hopefully by now, you've read about the signs and reversal of overtraining. Now let's look at why and how to train intelligently in-season. A well-designed in-season program should a) prevent overtraining and b) improve strength and power (for younger/inexperienced athletes) or maintain strength and power (older/more experienced lifters).

First off, why even bother training during the season?

1. Athletes will be stronger at the end of the season (arguably the most important part) than they were at the beginning (and stronger than their non-training competition).

2. Off-season training gains will be much easier to acquire. The first 4 weeks or so of off-season training won't be "playing catch-up" from all the strength lost during a long season bereft of iron.

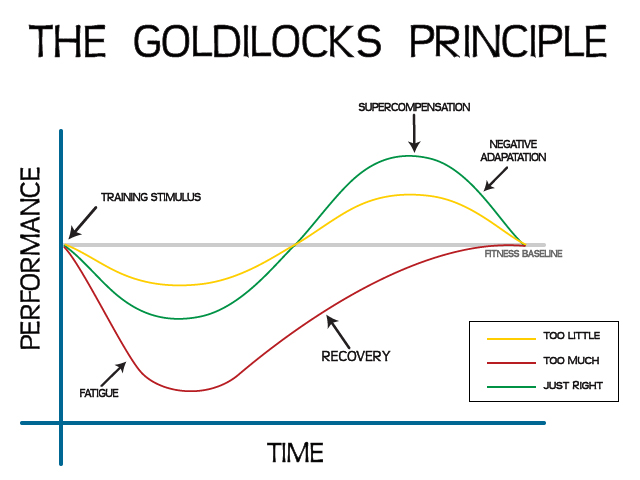

I know that most high school (at least in the uber-competitive Northern VA region) teams require in-season training for their athletes. Excellent! However, many coaches miss the mark with the goal of the in-season training program. (Remember that whole "over training" thing?) Coaches need to keep in mind the stress of practice, games, and conditioning sessions when designing their team's training in the weight room. 2x/week with 40-60 minute lifts should be about right for most sports. Coaches have to hit the "sweet spot" of just enough intensity to illicit strength gains, but not TOO much that it inhibits recovery and negatively affects performance.

The weight training portion of the in-season program should not take away from the technical practices and sport specific. Here are a couple of things to keep in mind about the program, it should:

1. Lower volume, higher intensity-- this looks like working up to 1-2 top sets of the big lifts (squat or deadlift or Olympic lift), while maintaining 3-4 sets of accessory work. The rep range for the big lifts should be between 3-5 reps, varied throughout the season. The total reps for accessory work will vary depending on the exercise, but staying within 18-25 total reps (for harder work) is a stellar range. Burn outs aren't necessary.

2. Focused on compound lifts and total body workouts-- Compound lifts offer more bang-for-your buck with limited time in the weight room. Total body workouts ensure that the big muscles are hit frequently enough to create an adaptive response, but spread out the stress enough to allow for recovery. Note: the volume for the compound lifts must be low seeing as they are the most neurally intensive. If an athlete can't recover neurally, that can lead to decreased performance at best, injuries at worst.

3. Minimize soreness/injury-- Negatives are cool, but they also cause a lot of soreness. If the players are expected to improve on the technical side of their sport (aka, in practice) being too sore to perform well defeats the purpose doesn't it? Another aspect is changing exercises or progressing too quickly throughout the program. The athletes should have time to learn and improve on exercises before changing them just for the sake of changing them. Usually new exercises leave behind the present of soreness too, so allowing for adaptation minimizes that.

4. Realizing the different demands and stresses based on position -- For example, quarterbacks and linemen have very different stresses/demands. Catchers and pitches, midfields and goalies, sprinters and throwers; each sport has specific metabolic and strength demands and within each sport, the various positions have their unique needs too. A coach must take into account both sides for each of their positional players.

5. Must be adaptable --- This is more for the experienced and older athletes who's strength "tank" is more full than the younger kids. The program must be adaptable for the days when the athlete(s) is just beat down and needs to recover. Taking down the weight or omitting an exercise or two is a good way to allow for recovery without missing a training session.

A lot to think about huh? As a coach, I encourage you to ask yourself if you're keeping these in mind as you take your players through their training. Athletes: I encourage you to examine what your coach is doing; does it seem safe, logical, and beneficial based on the criteria listed above? If not, talk to your coach about your concerns or (shameless plug here, sorry), come see us.