Are you a runner? Do you play a sport that involves running? Then you may be at risk for a groin injury. Read this to understand if you're at risk and check out these simple injury prevention exercises.

Coaching the Forearm Wallslide

A deceptively simple exercise, the forearm wallslide delivers a huge ROI:

To Overhead Press or Not to Overhead Press

I received this question from a friend of mine who is currently in physical therapy school and thought I'd share my response here. Q. Had a question. I know that at [X clinic he worked at] some of the therapists told me that overhead press was bad to do due to some impingement of the supraspinatus. This is also something we've learned in school but im not sure if this is specifically for those who just aren't strong enough or those recovering from injuries and such. Do you do overhead shoulder press w/ dumbells or BB and what is your take on the subject?

A. As usual, this is a question of contraindicated exercises versus contraindicated people. To make a blanket statement such as "no one should overhead press" would be both remiss and short-sighted. For example, if this is the case, should I avoid taking down and putting up my 5lb container of protein powder on top of my kitchen cabinet each morning? But I digress.

Getting to your the center of your question: Is the overhead press a fantastic exercise? Absolutely! Can the majority of the population perform it safely? Eh, not so much. In fact, this is a very similar subject matter to the back squat. The squat is arguably the greatest exercise to add lean body mass and increase athletic prowess, but may not be the wisest exercise selection depending on the person/situation. Chris actually addressed this very question in THIS post as to why he doesn't back squat the Division 1 baseball players he works with over at George Mason.

First things first: Look, I LOVE the overhead press. In fact, nothing makes me feel more viking-like than pressing something heavy overhead.In my personal opinion, the barbell military press is one of the BEST exercises to develop the deltoids, traps, serratus, and triceps, along with (if performing it correctly) the abdominals, glutes, low back, and upper thighs. HOWEVER, a lot of "stuff" needs to be working correctly in order to safely overhead press:

- Soft Tissue Quality

- Thoracic Mobility (specifically in extension)

- A Strong (and Stable) Rotator Cuff

- Upward Rotation of the Shoulder Blades

- General Ninja-like Status

Improved thoracic extension will positively alter your shoulder kinematics as you press overhead, a strong and stable cuff will help keep the humeral head centered in the glenoid (the shoulder socket) in order to free up that subacromial space (decreasing risk of impingement) , upward rotators will keep the scapulae in proper positioning, and I don't think I need explain how obtaining ninja status will help you overhead press like a champ.

If you can get all the things above up to snuff (via specific drills/exercises), then you're in pretty darn good shape. In reality, this comes down to ensuring you lay down a sound foundation of movement before loading up that very pattern. If the movement patterns and necessary kinematics are there, then chances are you get the green light to overhead press.

However, it doesn't stop there. A few other things need to be taken in to consideration:

1. Training Economy. If you only have X number of hours in the gym and Y capacity to recover, then you need to choose the Z exercises that will give you the most bang for your buck without exceeding your (or your athlete's) capacity to recover. Considering that the "shoulders" already receive tons of work from horizontal pressing movements (on top of horizontal and vertical pulling exercises), I really don't feel that most trainees - especially those that are contraindicated - need to overhead press if the primary goal is to further hypertrophy the deltoids and/or elicit some sort of athletic performance improvement.

2. Injury History. Partial thickness cuff tear? Labral fraying? Congenital factors? All these (and more) will come into play with deciding if overhead pressing will set you up for longevity in the realm of shoulder health.

3. Population. Are you dealing with overhead athletes? They're at much greater risk for the traumas listed in #2, and, not to mention, they already spend a large majority of their day with their arms overhead so you need to consider how mechanically stable (or unstable) their shoulder is, along any symptomatic AND asymptomatic conditions they may possess. Conversely, if you're dealing with a competitive olympic lifter, or an average joe who moves marvelously, then the overhead press may be a fantastic (or even necessary) choice to elicit a desired outcome.

4. Type of Injury. Ex. Those with AC joint issues may actually be able to overhead press pain free due to the lack of humeral extension involved (whereas the extreme humeral extension you'd find in dips or even bench pressing could easily exacerbate AC joint symptoms). Using myself as example, I can actually military press pain free, whereas bench pressing quickly irritates my bum shoulder. I don't have an AC joint issue (as far as I know...), but I've still found that my pain flares up when my humerus goes into deep extension (past neutral) in any press such as a pushup, barbell press, dumbbell press, etc. so the military press actually feels pretty good for me PERSONALLY. With regards to pushups and dumbbell pressing, I can usually do it fine as long as I'm cognizant to avoid anterior humeral glide.

As for pressing overhead with dumbbells vs. barbells, I find that, frequently, it's best to start someone with dumbbell pressing with a NEUTRAL grip (palms facing each other) as this will give your shoulder more room to "breathe" by externally rotating the humerus and lowering risk of subacromial impingement. From there, you can progress to the barbell as long as the items listed in the beginning are in check.

In the end, this comes down to how well you move, your posture, and your individual situation. With technology currently PWNING our society's movement patterns via increased time in cars, sitting in front of our computers, gaming, and overall sedentary lifestyle, we have to fight much harder than our ancestors to turn that "red light" to a "green light" in the sphere of overhead pressing.

Note: to conclude, feel free to watch the video below by Martin Rooney. Hopefully, you can read the central message portrayed:

It's All About the Glutes

When Bret Contreras first wrote this article, I thought he was nuts - along with just about every other strength coach across America. After all, who spends over 10 years (that isn't a paid researcher) reading almost every study, article, or book ever written on the glutes, and hooks up electrodes to his own butt to measure which exercises elicit the greatest glute involvement?! Not to mention, very rarely had people ever trained the glutes the way that Bret suggested we should, and I am always skeptical when so called "new and improved" exercises hit the public. The basics have worked for centuries, and this isn't going to change anytime soon.

The point is that this series of experiments revolutionized the way that strength coaches train people's glutes today. Basically, we've had it all wrong for quite a while now. As Bret mentions in the article:

"Despite the fact that the gluteus maximus muscles are without a doubt the most important muscles in sports and the fact that strength coaches helped popularized "glute activation," none of them have a good understanding of glute training..."

"..And second, athletes' glutes are pathetically weak and underpotentialized. Even people who think they have strong glutes almost always have very weak glutes in comparison to how strong they can get through proper training."

The cool thing, too, is that there were real-world improvements in athlete's performance when coaches began to train the glutes the way Bret teaches in the article (I make a point of this because there are many things that occur in the "scientists labs" that don't actually pan out in real life scenarios).

It makes sense, too, as (noted in the article) the gluteus maximus muscles are heavily involved in some of the most important movements in sport: sprinting, leaping, cutting from side to side, and twisting (the "geeky" way to describe this is that the glutes function to produce hip extension, hip hyperextension, hip transverse abduction, hip abduction, and hip external rotation).

So, after reading (and scoffing at, initially) about the way we "should" be training the glutes, I gave it a shot. After all, if Bret was right, this would mean enormous advancements in improving people's athletic performance, low back health, physique enhancement, and quite a few other bonuses.

After spending about a year training my glutes with more focus than I ever had in the past, I was shocked with the results. Below are two staple exercises (after progressing appropriately) one can perform for stronger glutes: the Barbell Glute Bridge and the Barbell Hip Thrust.

Here's a 555lb Glute Bridge:

You can then increase the range of motion the glutes have to work through (thus having to lower the weight). Here's a 435lb Hip Thrust:

Now, it is imperative that one knows how to properly use his or her glutes to do these exercises. Otherwise, the low back will take over the force production, which is a recipe for injury. I often joke on bodybuilders for their touting of the "mind-muscle" connection in lifting, but I actually have to say that this is of extreme importance in glute training. Weighted glute movements are phenomenal tools, but you need to know how to actually use your glutes (trust me, you're probably worse than you think) before attempting these.

It's all about cracking walnuts The cue I give myself (and anyone I coach) during any bridge variation is to "Crack a Walnut" between the butt cheeks. I wish I could remember where I got this coaching cue from, because it is brilliant. For some reason, people don't know how to bridge correctly when I say "use your glutes," but as soon as I say "crack a walnut between your butt cheeks" they know exactly what to do! As funny as it is, it's actually key to do this to ensure you're not just hyperextending your low back to achieve the range of motion desired.

Progressions Below is a BRIEF listing of some of the bodyweight progressions you can use (for more exercises, as well as suggested sets and reps, go back and read the article linked above):

How do YOU benefit (regardless of your occupation)? So why should anyone really care about this stuff? Whether or not you're an athlete, effective glute training provides incredible benefits. Rather than reinvent the wheel, I'll quote "the Glute Guy" himself:

"Athletic performance • Strong glutes will help you jump higher and farther • Strong glutes will help you run faster and with more efficiency • Strong glutes will help you cut faster from side to side • Strong glutes will help you rotate faster, which means throwing faster and farther, swinging faster, and striking faster • Strong glutes will help you lift heavier loads in the gym

Physique enhancement • Possessing a nice butt separates you from the pack. It’s actually quite rare to find someone with an amazing butt, and both sexes will agree that when they’re in the presence of such a booty, it’s hard to look away! Our primal urges kick in and our hormones go into overdrive. • If you want to look “athletic,” then you need glutes. The Men’s Health and Women’s Health look is all the rage these days for the general public, and you can’t achieve this look by just jogging and doing push ups and sit ups. • Figure competitors typically lose their glutes when they diet down. They need extra glute mass to counteract this phenomenon.

General health and injury prevention • Strong glutes encourage good lifting mechanics and less low-back rounding, which spares the spine and decreases low back pain and injury • Strong glutes prevent knee caving (Valgus collapse) which decreases the likelihood of knee (patellofemoral) pain and knee injury such as ACL tears. Strong glutes also spare the knee joint by encouraging proper lifting form and having the hips share the load when lifting rather than having the knee joint take on the brunt of the load • Strong glutes are one of the keys to overall structural health, as they set the stage for proper mechanics. Failing to use the glutes results in postural distortions (Lower-cross syndrome) which goes hand in hand with upper cross syndrome and can lead to groin strains, shoulder issues, spinal issues, Sciatica, and hip pain (anterior femoral glide syndrome) • Sound lifting mechanics involves using the glutes, which is a large, active muscle group, and good form is actually more costly from a metabolic perspective in comparison to lifting in ways that don’t involve the glutes, so strong glutes burn more calories during everyday movement which will help get you leaner"

I would also like to add myself that glute strength aids in injury risk reduction of the hamstrings. How many of you know someone that has been through a hamstring pull/strain/tear? My guess is the great majority. One of the leading contributing factors to hamstring injuries is poor glute function!

Both the hamstrings and glutes function extend the hip in sprinting. However, when the glutes aren't doing their full job, the hamstrings will try to "take over" the movement and bear the brunt of the force production. The physiological term for this is "synergistic dominance." This usually results in some sort of hamstring injury and one point or another.

I'd say this is plenty reason to begin glute training! If you walk into SAPT, you're likely to see many athletes - as well as adults - performing some variation of glute bridging. Many of our high school guys are Barbell Bridging 300lbs+, and we've had quite a few females hit the 135lb mark.

Now (and I'll end with this), glute variations are no substitute for proper squatting, deadlift variations, and single-leg work when it comes to effective strength training. However, when combined with the staple lifts, this creates an outstanding synergistic effect in enhancing athletic performance.

Now go start training those glutes.

Torch Your Hammies with The Band-Assisted Sissy Ham

Confession: I have weak hamstrings. Very weak hamstrings. As such, I’ve needed to ensure that my training includes exercises that will bring up the strength of those stubborn muscles on the back of my legs. In the process of solving this dilemma, I came up with an exercise that will also help athletes improve their performance via stronger hamstrings. Now, one of the last exercises we would have one of our (healthy) athletes perform to increase their hamstring strength is the leg curl.

For most, they’re a terrible waste of time (yes, they certainly have a place in rehab settings and with older/deconditioned individuals, and bodybuilders could make an argument for them). While the majority of people understand that hamstrings function to flex the knee - which is what the leg curl trains - they often neglect that the hamstrings play a CRITICAL role in hip extension. The hamstrings are the body’s second most powerful hip extensor – just behind the glute max! (pun fully intended) For athletes, strong hamstrings can be invaluable as they play crucial role: resisting (eccentrically) knee flexion during sprinting. Take home point: stronger hamstrings make you faster!

As they say, necessity is the mother of invention. Enter the Band-Assisted Sissy Ham (or “Russian Leg Curl”). I came up with this exercise as I was helping some of our athletes perform pullups with band assistance. I had an “ah-ha” moment and decided to find a way to give myself (and others) band assistance during the sissy ham. In the video below, the first half will show me performing the sissy ham without the band. Then, I perform it with the aid of a band (attached above me). Notice there is now no arm push needed to help on the concentric (the “up”) portion of the lift.

(Note: Yes, upon looking at this video in retrospect, my pelvis is slightly tilted anteriorly and there's a bit of excessive low back arch. If I could travel back in time a year I'd go kick my own arse. Comon' Stevo! Get it right. Geez....)

This is such a fantastic exercise as it trains, simultaneously, both functions of the hamstrings: knee flexion and hip extension (which is how our hamstrings are utilized in athletics, anyway). It also makes for a more tangible progression than the regular sissy ham/russian leg curl. As you get stronger, you can lessen the band tension (as opposed to subjectively measuring "how fast you fall" during the regular sissy ham).

If you don't have a power rack that makes it easy to set up something like this, you could either just have someone manually hold your ankles, or latch your ankles under the pads of a lat pulldown apparatus (your knees would be resting where your butt normally goes). Then all you need is a sturdy 1/2" or 1/4" resistance band, which can be purchased through companies like Iron Woody, Perform Better, or EliteFTS.

As strength coaches, our mission (behind keeping people healthy) is to improve movement quality, performance, and strength and power. We also have only, roughly, 150 minutes a week to do this. This being the case, you won't find us filling 10 of those 150 minutes wasting time on an isolated leg curl. I could think of a million things athletes would be better off spending their time doing (placing their hand on a heated frying pan being one of them). Even if you're not an athlete, this exercise will still be wayy more beneficial for developing your hamstrings than the leg curl. It will also work well for the long-distance runners in the crowd!

This exercise isn't appropriate for everyone, as it's EXTREMELY difficult, even though it may not appear so if you haven't tried it. I definitely recommend a healthy dose of glute walks, slider hamstring curl eccentrics, and hip thrusts before attempting something like this.

How Low Should You Squat?

I was hanging out with some good friends of mine over the weekend, and one of them asked me about a hip issue he was experiencing while squatting. Apparently, there was a "clicking/rubbing sensation" in his inner groin while at the bottom of his squat. I asked him to show me when this occurred (i.e. at what point in his squat), and he demoed by showing me that it was when he reached a couple inches below parallel. Now, I did give him some thoughts/suggestions re: the rubbing sensation, but that isn"t the point of this post. However, the entire conversation got me thinking about the whole debate of whether or not one should squat below parallel (for the record, "parallel," in this case means that the top of your thigh at the HIP crease is below parallel) and that"s what I"d like to briefly touch on.

Should you squat below parallel? The answer is: It depends. (Surprising, huh?)

The cliff notes version is that yes in a perfect world everyone would be back squatting "to depth," but the fact of the matter is that not everyone is ready to safely do this yet. I feel that stopping the squat an inch or two shy of depth can be the difference between becoming stronger and becoming injured.

To perform a correct back squat, you need to have a lot of "stuff" working correctly. Just scratching the surface, you need adequate mobility at the glenohumeral joint, thoracic spine, hips, and ankles, along with possessing good glute function and a fair amount of stability throughout the entire trunk. Not to mention spending plenty of time grooving technique and ensuring you appropriately sequence the movement.

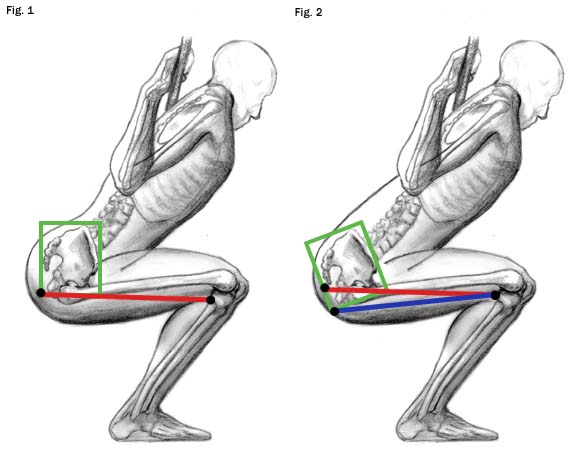

Many times, you"ll see someone make it almost to depth perfectly fine, but when they shove their butt down just two inches further you"ll notice their lumbar spine flex (round out), and/or their hips tuck under, otherwise known as the Hyena Butt which Chris recently discussed.

If you can"t squat quite to depth without something looking like crap, I honestly wouldn"t fret it. Take your squat to exactly parallel, or maybe even slightly above, and you can potentially save yourself a crippling injury down the road. It amazes me how a difference of mere inches can pose a much greater threat to the integrity of one"s hips or lumbar spine. The risk to reward ratio is simply not worth it.

The cool thing is, you can still utilize plenty of single-leg work to train your legs (and muscles neglected from stopping a squat shy of depth) through a full ROM with a much decreased risk of injury. In the meantime, hammer your mobility, technique, and low back strength to eventually get below parallel if this is a goal of yours.

Not to mention, many people can front squat to depth safely because the change in bar placement automatically forces you to engage your entire trunk region and stabilize the body. You also don"t casino online have to worry about glenohumeral ROM which sometimes alone is enough to prevent someone from back squatting free of pain.

Also, please keep in mind that when I suggest you stop your squats shy of depth I"m not referring to performing some sort of max effort knee-break ankle mob and then gloating that you can squat 405. I implore you to avoid looking like this guy and actually calling it a squat:

(Side note: It"s funny as that kind of squat may actually pose a greater threat to the knee joint than a full range squat....there are numerous studies in current research showing that patellofemoral joint reaction force and stress may be INCREASED by stopping your squats at 1/4 or 1/2 of depth)

It should also be noted that my thoughts are primary directed at the athletes and general lifters in the crowd. If you are a powerlifter competing in a graded event, then you obviously need to train to below parallel as this is how you will be judged. It is your sport of choice and thus find it worth it to take the necessary risks of competition.

There"s no denying that the squat is a fundamental movement pattern and will help ANYONE in their goals, whether it is to lose body fat, rehab during physical therapy, become a better athlete, or increase one"s general ninja-like status.

Unfortunately, due to the current nature of our society (sitting for 8 hours a day and a more sedentary life style in general), not many people can safely back squat. At least not initially. If I were to go back in time 500 years I guarantee that I could have any given person back squatting safely in much less time that it takes the average person today.