Part 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum

Triathlete Strength Training PrimerPart 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum

Hello SAPT blog readers! I trust you all had a great week, and are eager to learn more about strength training and the myriad of benefits it has to offer. We talked about periodization in our last blog post, but how about a quick recap.

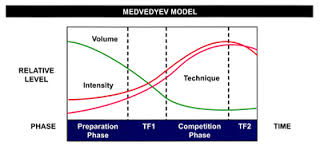

Periodization is the manipulation of exercise selection, intensity, and the set/rep scheme throughout the year in order to provide optimal results. We use periodization in order to avoid entering a state of overtraining, take a more intelligent approach to our training methods, and maintain long-term athletic development. The conventional model of periodization involves four distinct phases: the preparatory period, first transition period, competition period, and second transition period.

During each of these phases, we manipulate the intensity of our training loads, by either removing or adding weight to the bar, in order to stress different performance attributes. But, what types of performance attributes are there?

Well, we have strength, for one. Strength is usually thought of in terms of absolute strength, which would be the maximum amount of force a muscle or muscle group can produce. The main objective of a powerlifter is to increase their absolute strength as much as possible in order to lift enormous loads. We can also train for power, which is defined as the amount of work done per unit of time. Power is the rate at which work is being performed, and is especially relevant to athletes that are required to compete for shorts bursts of time. A hockey player or football lineman would be wise to spend a significant amount of time training to improve their power. Last, but not least, we can train for muscular endurance. Obviously, a marathon runner or triathlete aims to improve their endurance above all else. Success in these two sports demands a huge aerobic engine from the athlete.

This is where the repetition maximum continuum comes into play. The numbers on the figure to the right order <2 through 20. These refer to the amount of repetitions of a given exercise we are performing with a given weight.

Therefore, the 4 on the figure would refer to a weight that you can lift 4 times, and only 4 times. For example, Jim can perform a back squat with 225 pounds 4 times, but will not be able to lift it for a fifth rep. If he added weight to the bar, he would not be able to complete 4 repetitions. 225 pounds is Jim’s 4-rep max (4RM).

As you can see, these different performance attributes exist on a continuum. Strength is trained to a very high degree when training in the 2 to 5 rep range, but it is also trained slightly when we are lifting lighter weights for sets of 15. As a matter of fact, power follows a similar trend. The continuum tells us it’s important to lift heavy loads when we are focused on training to improve our strength or power, and lighter loads if we are attempting to improve our muscular endurance. We will still see improvements in strength and power when working with these lighter loads, but they won't be as dramatic as when we were working with heavy weights.

You may notice there is a “hypertrophy” range according to this continuum. Traditionally, research has led us to believe that working in the 8-12 rep range has been superior for building size. There is a recent study performed by Brad Schoenfield et al. that seems to dispute this theory.

The researchers took 20 participants who had been weight training for at least 1.5 years previously, and separated them into two groups. One group performed a bodybuilding style program, lifting lighter relative loads for more repetitions (3x10 reps per exercise), while the other group performed a traditional powerlifting style program lifting heavier loads for fewer reps (7x3 reps per exercise). The goal was to examine the effect lifting different relative intensities would have on muscle growth, so the researchers made sure the total amount of weight lifted (volume, or total tonnage) was equal between the groups.

After 8 weeks of weight training, the researchers found that both groups experienced a similar amount of muscle growth (the biceps brachii was measured and both groups achieved about a 13% increase in size), but that the powerlifting group experienced significantly greater improvements when it came to strength. This tells us that there may not be a magical “hypertrophy” range after all. The comparison of two different styles of lifting while accounting for volume implies that muscle growth is largely genetic, and will occur to similar extents if you are following a program based on the principle of progressive overload regardless of the exercise intensity.

One very important takeaway from the study was the physical toll each program had on its participants. The lifters who followed the bodybuilding protocol experienced far less fatigue and injury (2 powerlifters had to drop out due to joint injury), as well as spent much less time in the gym (17 min vs 70 min) then the powerlifting group.

What can we extrapolate from this? Performing a program that utilizes lighter relative loads and a higher rep range will allow us to build muscle size while limiting the amount of stress we are subjecting our joints to, however, we will never see optimal strength gains training this way. Therefore, it is imperative for triathletes to spend some time in the lower rep/higher weight side of the continuum in order to improve strength and power.

Also, we know that our bodies adapt to stress through the S.A.I.D. principle (Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands), and we experience diminished returns as a result of consistent training. This means we will adapt to whatever specific stress we are applying to our body in a specific manner, and, as time goes on, we will see less and less of an improvement if we continue to apply the same stimulus.

This is why periodizing our training is so important! We want to cycle the type of stress we are applying to our body in order to drive performance improvements. By rotating between heavy, moderately heavy, and moderate loads, we’re working to improve different performance elements dictated by the repetition maximum continuum. As triathletes, there will be certain times of the year that we want to focus on improving our muscular endurance, and certain times of the year when we really need to be focusing on strength or power production. The challenge is to determine when to focus on each, and as we continue through the series, I’m going to teach you how to do just that.

Stay tuned for next Thursday’s post, where we will begin to break down the preparatory period and what a triathlete should be focusing on during the off-season.

The Triathlete Strength Training Primer

Part 1: An Intro to Periodization - Seeing the Bigger Picture Part 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum Part 3: The Preparatory Period a.ka. the Off-Season Part 4: Off-Season Periodization Part 5: Off-Season Periodization, cont. Part 6: The First Transition Period Part 7: The First Transition Period, cont. Part 8: The Competition Period - In-Season Strength Training Part 9: In-Season Template Part 10: Post- Season Training

Go Navy, It's Your Birthday

In honor of the US Navy turning the big 239 on Monday today’s blog post will discuss ways to prepare one for the upcoming Navy Physical Readiness Test (PRT). Sailors perform the PRT which consists of a 1.5 mile run along with a 2 minute push up and curl up test twice each year. These sailors can also choose to do a 500 meter swim for time instead of the run. Like the civilian world some people really enjoy exercise and training while some prefer to join the 3 mile per year club and only run when forced to do so.

Regardless of these differences, listed below are a few simple tips to help you with the components that comprise the PRT along with many other military and public service readiness tests There is a bit of a crossover effect as certain military branches or agencies share test components such as a timed run. The Army requires a 2 mile run while Marines are required to run 3 miles.

The Run

Wear running shoes: Your Air Force Ones (The shoes) may give you a ton of support and jump height on the basketball court; however these or a set of worn out shoes from years ago are not only going to slow you down but they can also create extra stress and damage to your feet, knees, hips, and back.

Fix your form: A few simple fixes to your running form can make a big difference in how quickly you reach the finish line. Erratic (and weird) arm movements and excessively slapping or stomping of your feet into the ground every step is a waste of energy and tires you quickly. A good drill to correct “loco arms” is to do a few short runs with a focus on having your wrists lightly brush your ribs while keeping a 90 degree bend at your elbows.

Push Ups

Do more push ups: Yes, doing more push ups will make you better at push ups. Any easy way to increase your daily push up volume is to spread a few sets out throughout the day. Maybe during commercial breaks or in line at Chipotle.

Add variety to these push ups by varying your hand (wide or elevated) and foot (elevated or single leg) positions.

Shore up your core: Spend some time doing plank and push up position plank (PUPP) variations to increase endurance so that you have the stability to perform long sets of push ups.

Curl Ups

It would be foolish of me to say “go bang out curl ups all day”. The most important concept of training for this event is to focus on training the abdominal and low back regions equally via a variety of training methods to increase the stability and endurance of all of the surrounding musculature. Listed below are a few videos to help:

Take these words and set sail on your path to the upper echelon of physical readiness, no matter your branch or agency and have some cake for big Navy.

Early Sport Specialization: Why This Needs to Stop (with a capital "S")

I wrote this post a few months back, but I thought it tied in nicely with my prior two posts on overtraining (here and here). My hope is that if athletes, parents, and coaches read this information enough, the message of the necessity of REST will percolate through the athletic world. Perhaps then we'll see a decline in young athlete injuries instead of the worrisome increase occurring now. Here in northern Virginia, and in other hub-bub places too, it's not uncommon for an athlete to play a sport during the high school season, and then transition straight into the club season (which lasts f-o-r-e-v-e-r), leaving the athlete with maybe 2-3 weeks rest before try-outs for the next year's high school season start. Does this sound familiar? Does this sound healthy?

Today we're going to address a growing (alarmingly so) problem with youth athletics: early sport specialization. As a strength coach, I see some messed up kids when it comes to movements, joint integrity, and muscle tissue quality (all = poop) who play year-round sports at young ages (that is, under 16-17 years old). I see year-round volleyball players who can't do a simple medicine ball side throw.

Why? Because they spend ALL YEAR moving in the sagittal (forward/backward) plane with a little bit of the frontal plane (side to side shuffling, but even that is dominated by their inability to actually move sideways; they tend to fall forward and/or move as if they're running forward, just facing a little bit to the side. I wish I was exaggerating.) They have limited movement landscape (remember this?) and therefore are limited athletes.

I see young baseball players with chronic elbow or shoulder pain. Why? Because they throw a ball the same way ALL YEAR ROUND. And they're not strong enough to produce the force needed to throw it properly, (because, heaven forbid, they take some time off to actually weight train and grow bigger and stronger) so they rely on their passive restraints (ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules) to throw.

This topic gets me fired up because I see SO MANY injuries, nagging aches, and painful joints in kids who shouldn't feel (and move) like they're 85 years old. I see kids who can't move like a normal human being because they're locked up and, worse, don't even have the mind-body connection to create movements other than those directly related to their chosen sport.

There's this pervasive myth that if a kid doesn't play year round or get 10,000 hours of practice, then he/she will never be a good athlete. Parents get swept up in chasing scholarships and by golly, if Jonny doesn't play travel ball he'll fall behind, then he won't make varsity, then he won't get into a good college... and on and on. My friends, we need to take a step back and think about what's best for the athlete. Do the aforementioned afflictions sound good to you?

But enough of my opinion, let's look at some hard science to support the Stop-Early-Specialization-Theory.

Playing multiple sports and playing just for the sake of running around like a kid builds a rich, diverse motor landscape, especially during the years before late adolescence. Diversifying the motor landscape, or movement map, or the bag-o-skillz, or whatever you want to call it, is essential to human development and especially valuable to athletes. As Jarrett mentioned in his post (linked above), kids need a broad and varied map to:

1. Understand how to move their bodies through space

2. Create and learn new movements

3. Learn how to adapt to their environment

4. Develop better decision-making and pattern recognition skills based on their circumstances (i.e. being able to find the "open" players in a basketball game helps in finding one on the soccer field. )

Matter fact, this really smart fellow, Dr. John DeFirio MD, who is the President of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, Chief of the Division of Sports Medicine and Non-Operative Orthopaedics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Team Physician for the UCLA Department of Intercollegiate Athletics (that's quite the title, eh?) says this:

"With the exception of select sports such as gymnastics in which the elite competitors are very young, the best data we have would suggest that the odds of achieving elite levels with this method [early sport specialization] are exceedingly poor. In fact, some studies indicate that early specialization is less likely to result in success than participating in several sports as a youth, and then specializing at older ages"

And, Dr. DiFiori encourages youth attempt to a variety of sports and activities. He says this allows children to discover sports that they enjoy participating in, and offers them the opportunity to develop a broader array of motor skills. In addition, this may have the added benefit of limiting overuse injury and burnout.

You can read his full article here. The article also notes two studies in which NCAA Division 1 athletes and Olympic athletes were surveyed regarding what they did as children. Guess what? 88% of the NCAA athletes played 2-3 sports as kids, and 70% of them didn't specialize until after age 12. The Olympians also all averaged 2 sports as kids Are you picking up what he's putting down? Specialization doesn't make great athletes, diversification does!

Side bar: Check out Abby McCollum, who played 4 sports for a Division 1 school. The article says that she was recruited last minute... probably because she was such a great all-around athlete that she could play any sport.

Next up: injuries rates.

Dr. Neeru Jayanthi, a sports medicine physician, in conjunction with Loyola University published a few studies using a sample set of 1,026 athletes between ages 8-18 who came into the Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago for either sports physicals or treatment for sports-related injuries. The study ran from 2010 to 2013. Dr. Jayanthi and her collegues recorded 859 injuries, of which 564 of them were overuse injuries (that's well over HALF, people). Of those 564 injuries, 139 of them were serious injuries concerning stress fractures in the back or limbs, elbow ligaments or injuries to the cartilage. All of these injuries are debilitating and can side line and athlete for 6 months or more. The broad study is reviewed here and a more specific cohort (back injuries, which carry into later in life) is here. I highly recommend reading both as the data are eye opening.

To sum up Dr. Jayahthi and co.'s recommendations on preventing overuse injuries (I took it directly from one of the articles in case you don't have time to read them both):

• If there's pain in a high-risk area such as the lower back, elbow or shoulder, the athlete should take one day off. If pain persists, take one week off. (though I think it should be more)

• If symptoms last longer than two weeks, the athlete should be evaluated by a sports medicine physician. (and go get some strength training! There's a reason that pain is occurring; something is overworking for something else that's NOT working.)

• In racket sports, athletes should evaluate their form and strokes to limit extending their backs regularly by more than a small amount (20 degrees). (this should also apply to any overhead sport like volleyball, baseball, softball, etc.)

• Enroll in a structured injury-prevention program taught by qualified professionals. (hey, like SAPT? Lack of strength is a common denominator among injured athletes.)

• Do not spend more hours per week than your age playing sports. (Younger children are developmentally immature and may be less able to tolerate physical stress.) (10 year-olds don't need 12 hours or soccer! Also check out Dr. Jayahthi's injury prediction formula.)

• Do not spend more than twice as much time playing organized sports as you spend in gym and unorganized play. (Kids, go play tag, get on the playground, play capture the flag, anything; JUST PLAY!)

• Do not specialize in one sport before late adolescence.

• Do not play sports competitively year round. Take a break from competition for one-to-three months each year (not necessarily consecutively).

• Take at least one day off per week from training in sports.

The highlights and comments are mine. Do you see the RISK involved in specializing in a sport early in life?

Not only does the risk of injury skyrocket, and the ability to move fluidly and easily plummet, but there's a lot of external pressure on the athlete to perform. Stressed athletes don't perform well. I don't know how many times I've asked my year-round players what they're doing on the weekends, it's always "tournament" or "practice." They have NO LIFE outside of sports. To me, that seems unhealthy and frankly, a recipe for burn-out.

Parents, athletes, and coaches, in light of all this research, I urge you to strongly reconsider year-round playing time for kids under 16 or 17. I urge you to allow athletes time off, to play other sports besides they're favorite, and to just be a kid. I urge you to keep the long-term development of our athletes in mind; do you want to risk a permanent injury, hatred of sport (because of burn out), or development of weird compensations and movement patterns?

Let's build strong, robust athletes that can do well in the short- and long-term instead of pigeon-holing them into a particular sport and limiting their athletic potential.

Part 1: An Intro to Periodization - Seeing the Bigger Picture

Triathlete Strength Training PrimerPart 1: An Intro to Periodization – Seeing the Bigger Picture

Last week, I wrote about how strength training can benefit the endurance athlete and why you would be remiss to skip a lifting session. Fortunately for me, my readers were paying attention and have been thoroughly convinced that weight training will indeed make them better endurance athletes. Now that we’re ready to attack the weight room, let’s use the next couple of weeks to take a step back and see how we should approach our training and, more importantly, how it changes throughout the year. I will be focusing strictly on the triathlete for this series, but the concepts can be applied to any and all athletes.

Periodization. What is periodization? According to the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA), periodization is defined as preplanned, systematic variations in training specificity, intensity and volume, organized in periods or cycles within an overall program. In other words, we manipulate the exercises we’re training, the percentage of our 1RM that we are training with, and the set/rep scheme we are using based on the time of year when planning a comprehensive training plan. We organize training in this manner to ensure we’re doing all we can to create a program that encourages long-term athletic development and success, while minimizing the risk of injury and overtraining.

Leo Matveyev, a Russian physiologist, is recognized as one the father’s of periodization and his work has been modified throughout the years by various exercise scientists for different populations. The conventional periodization model that strength coaches use is a variation of Matveyev’s model, and it separates training into distinct periods: the preparatory period, first transition period, competition period, and second transition period. Each period presents an opportunity to train different performance qualities and will be briefly defined below.

1) The Preparatory Period: This phase is typically the longest, and occurs during the time of year when there are no scheduled competitive events and minimal sport-specific training sessions. The primary emphasis is on building a base level of conditioning and strength with general exercise selection in preparation for more intense training and the rigors of the competitive season. This can be referred to as the athlete’s “Off-Season.”

2) The First Transition Period: This phase occurs immediately following the end of the Preparatory Period, and emphasizes the switch from high-volume to high-intensity training. The exercises become increasingly sport-specific and technique becomes a major focus. This can be considered the athlete’s “Pre-Season.”

3) The Competition Period: This phase follows the First Transition Period, and our focus is solely on peaking the athlete’s strength, power, and performance for competition. Our athlete is “In-Season” during this time.

4) The Second Transition Period: This phase can be referred to as our “Active Rest” phase, and should last long enough to allow the athlete to completely recover from the competitive in-season. We want to encourage non-sport-specific recreational activities performed at low intensities during this time. It’s important to avoid intense training during this period to allow complete physical and mental recuperation.

Having this basic knowledge of periodization is incredibly important for maintaining long-term success. It’s critical to understand the bigger picture when it comes to our training, so that we can take a more intelligent approach to developing our athletic performance.

That’s all for today’s post, but stay tuned for Part 2 which will be up on the blog next Thursday (10/16). We'll be discussing the Repetition Maximum Continuum, and how we train to enhance performance attributes, not for subjective visual purposes (ex: to tone or lengthen muscle). This post will be absolutely vital in order to properly grasp training methods throughout the competitive year.

The Triathlete Strength Training Primer

Part 1: An Intro to Periodization - Seeing the Bigger Picture Part 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum Part 3: The Preparatory Period a.ka. the Off-Season Part 4: Off-Season Periodization Part 5: Off-Season Periodization, cont. Part 6: The First Transition Period Part 7: The First Transition Period, cont. Part 8: The Competition Period - In-Season Strength Training Part 9: In-Season Template Part 10: Post- Season Training

Strongman Training for Sports

Today’s blog post will focus on how strongman activities can be used to benefits athletes of a variety of sports. Surely, at some point you were channel surfing and found a giant man on ESPN pulling a dump truck or some other amazing feat of strength. You also probably watched for a few minutes in shock and awe but later realized that many of the activities performed in strongman are the same movement we perform in the gym with barbells.

The sport of Strongman requires strength, speed-strength, core stability, a high work capacity, grip strength, and dynamic flexibility. All of these are great skills to have in many mainstream sports like wrestling, basketball, or hockey. Below we will discuss a few strongman exercises that any athlete could benefit from.

Farmer’s Walk

This is the granddaddy of them all. There is nothing more “functional” than picking something heavy up and carrying it. Athletes and non-athletes alike have performed this exercise for as long as we been on earth, whether carrying groceries in from the car or hauling bags through Dulles. One of the purposes of the core muscles is to resist movement in the trunk and this is a great exercise to teach core stabilization while the legs are moving. To get creative with this exercise, you can modify the implement you use. For example, a kettlebell, barbell, or 4x4’s (the wooden kind) if you want to challenge your grip strength. Have fun and get innovative.

Tire Flip

The tire flip is another classic strongman exercise that is an athletic movement and physically taxing. Just a few flips of a moderately sized tire are sure to wake up all of your muscles. The hardest part of this exercise may be locating a tire but if you can get your hands on one, use it. It is crucial during this exercise to maintain proper technique and keep your spine out of risky positions. When performing the tire flip, it’s also helpful to think of this movement as an explosive lift off the ground followed by a violent push once the tire reaches its tread. When performed this way it is obvious to see how the movement could be helpful to offensive lineman who on each play must explode out a 3 point stance and take on a defender.

Sled Work

There are a multitude of variations for sled work and all of them train the body to work as a whole unit so this another great time to try out the many available alternatives. First, let’s look at forward pulling or towing. Strapping on a harness or belt and towing a weighted sled (or Volvo) is an excellent way to build strength and stability in the ankles, knees, and hips. This comes in handy for any athlete required to run or swimmers who need a strong push off the wall. Hand over hand rope pulling of a sled is a fantastic exercise to develop grip and bicep strength and pulling power for sports like wrestling and lacrosse.

If you are interested in full body strength, stability, explosiveness, power, balance, and overall toughness give some of the strongman movements or their variations a try and see how they help improve your performance. If those sound like horrible attributes (I’m surprised you read this far) stay weak and prosper.

Overtraining Part 2: Correct and Avoid It

In the last post, we went over some symptoms of overtraining. If you found yourself nodding along in agreement, then today’s post is certainly for you. If not, well, it’s still beneficial to read this to ensure you don’t end up nodding in agreement in the future.

To clarify, overtraining is, loosely, defined as an accumulation of stress (both training and non-training) that leads to decreases in performance as well as mental and physical symptoms that can take months to recover from. Read that last bit again: M.O.N.T.H.S. Just because you took a couple days off does NOT mean your body is ready to go again. The time it takes to recover from and return to normal performance will depend on how far into the realm of overtraining you’ve managed to push yourself.

Let's delve into recovery strategies. Of the many symptoms that can appear, chronic inflammation is a biggie. Whether that’s inflammation of the joints, ligaments, tendons, or muscles, it doesn’t matter; too much inflammation compromises their ability to function. (A little inflammation is ok as it jumpstarts the recovery process.) Just as you created a training plan, so to must you create a recovery plan for healing after overtraining.

Step 1: Seek to reduce inflammation.

How?

- Adequate sleep is imperative! As in, go to bed BEFORE 11 or 12 PM teenagers-that-must-awaken-at-6AM-for-school. (Subtleness is not my strong suit.) Conveniently for us, our bodies restores themselves during the night. They release anabolic hormones (building hormones) such as growth hormone (clever name) and sleep helps reduce the amount of catabolic (breaking down) hormones such as cortisol. Since increased levels of coritsol are part of the overtrained symptom list, it would be a good thing to get those levels under control!

- Eat whole foods. Particularly load up on vegetables (such as kale) and fruits (like berries) that are rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds. Apparently Gold Milk has those, too and, according to Jarrett, helps him sleep. Bonus! Lean protein sources like fatty fish, chicken breast, and leaner beef (grass-fed if you can get it) will not only help provide the much-needed protein for muscle rebuilding but also will supply healthy fats that also help reduce inflammation.

- Drink lots of water. Water helps the body flush toxins and damaged tissues/cells out and keeps the body’s systems running smoothly. Water also lubricates your joints, which if they’re beat up already, the extra hydration will help them feel better and repair more quickly. A good goal is half your body weight in ounces of water guzzled.

Step 2: Take a week off

You’re muscles are not going shrivel up, lose your skill/speed, nor will your body swell up with fat. Take 5-7 days and rejuvenate. Go for a couple walks, do mobility circuits, play a pick-up basketball game… do something that’s NOT your normal training routine and just let your body rest. Remember, the further you wade into the murky waters of overtraining, the longer it will take to slog your way out.

Step 3: Learn from your mistakes.

While you’re taking your break, examine what pushed you over the edge. Was it too high of a volume and/or intensity? Was it too many days without rest? Was your mileage too high? Are there external factors you’re missing? Were you were stressed out at work/school, not sleeping enough, or maybe you weren’t eating enough or the right foods to support your activity. I’ve learned that I need 2 days of rest per week, any less than that and my performance tanks.

Step 4: Recalculate and execute.

When you’re ready to come back, don’t be a ninny and do exactly what you were doing that got you into this mess in the first place. Hopefully, you learned from your mistake(s) and gained the wisdom to make the necessary changes to avoid overtraining in the first place. Here, let’s learn from my mistake:

I overtrained; and I mean, I really overtrained. I had all the symptoms (mental and physical) for months and months. I was a walking ball of inflammation, every joint hurt, I was exhausted mentally and physically (and, decided to make up for my exhaustion by pushing myself even harder.) I ignored all the warning signs. This intentional stupidity led to my now permanent injuries (torn labrums in both hips, one collapsed disc in my spine, and two bulging discs). The body is pretty resilient, but it can only take so much. I ended up taking four months off, completely, from any activity beyond long walks. (That was terrible by the way. I hated every minute but knew it was necessary.) When I did come back, I had to ease into it. Very. Very. Slowly. Even then, I think I pushed it a bit too much. It took me almost 2 years to return to my normal physical and mental state. (Well, outside of the permanent injuries. Those I just work around now.) Learn from my mistake.

So how can we avoid overtraining? Here are simple strategies:

1. Eat enough and the right foods to support your activities.

2. Take rest days. Listen to your body. If you need to rest, rest. If you need to scale back your workout, do so.

3. Keep workouts on the shorter side. Avoid marathon weight lifting sessions (trust me). Keep it to 1-1.5 hours. Max. Sprint sessions shouldn’t exceed 15-20 minutes.

4. Sleep. High quality sleep should be a priority in your life. If it isn’t, you need to change that.

5. Stay on top of your SMR and mobility work. I wrote about SMR here and here.

6. Train towards specific goals. You can’t be a marathon runner and a power lifter. Pick one to three goals (that don’t conflict with each other) and train towards them. You can’t do everything at once.

Armed with the knowledge of overtraining prevention, rest, recover, and continue in greatness!