4 Drills to Clean Up a Hinge Pattern

Drills are an awesome and totally underutilized tool within most exercise programs. It's not hard to fall into the mindset of always needing to get stronger within a movement rather than just getting better at it through practice. This is CRUCIAL for people just beginning their strength training program as their initial gains are all based off of just learning how to do things, and thus can be expedited through the extra practice.

Hearing the term, "drill" also changes the mindset of the client. When you address a simple movement as an exercise, often times the client will be more aggressive in execution as they try to, "feel the burn" or fight you to let them go heavier. But when introducing a drill, it's often understood that the purpose is to learn the finer points of the movements and focus on technique. It then becomes immensely easier to progress the movement, blow through the noob gains or even clean up technique in more advanced lifters.

I personally find that the general population has the hardest time getting down their hinge pattern. This is most likely attuned to picking up things the wrong way on a daily basis combined with the whole factor of glute amnesia. It's for this reason that I've started using hinge drill variations in almost everyone's programs to help with their deadlift without having to worry about fatiguing the movement. I find that it helps with clients of all levels and experience.

The following are some of the most common drills you'll see us use at SAPT in the order of less to more advanced. Keep in mind that for people starting off, they are best paired with glute activation drills to help build stability in the posterior chain during the pattern.

Knees Against Bench Dowel Rod Hinge Drill

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2lHamIPidrc

This drill is awesome for all levels of lifters. To perform it, set up with your knees about an inch or two(everyone will be different) from a bench and hold a dowel rod against the back of your head, thoracic spine, and sacrum. Once set, push your hips back as you allow your knees to touch the bench. Go as far back as you can without letting you knees come off the bench or letting the dowel rod come off your head, point on your t-spine or sacrum. Come back out of the hinge and do not let your knees leave the bench until you are almost to lockout. Keep your feet relaxed and planted the entire time. Ideally one hand will be in the space of your lordotic curve to help give better feedback of if your back starts to round. If the knees come off the bench, you've sacrificed hip extension for knee extension. If the dowel rod leaves you, then you've lost your neutral spine. ONLY GO AS FAR AS YOU CAN WHILE MEETING THESE REQUIREMENTS.

This drill has become a staple for beginners at SAPT and I have found it to reinforce a correct hinge pattern faster than any other corrective. As previously stated, I often like to combine it with floor-based glute activation exercises to help give the client more posterior chain stability and allow them to hinge further back. Also, for more quad-dominant individuals, I will abuse this exercise during their rest periods. It's not uncommon for you to see 10 sets of 10 to be performed throughout the session.

This is an(especially) appropriate drill for anyone who has the following issues:

- Locks out knees before hips

- Has trouble keeping a neutral spine

- Has a poopy ASLR and is not yet ready for deadlifts(especially when combined with the next on the list)

- Poor posterior weight shift ability

Band Resisted Quadruped Rock

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VrRzZypg-cM

This drill looks odd at first(especially when performed by Waldo), but it can be pretty powerful when used correctly. Due to the knees being unable to translate during the movement, it shifts the entire focus to the hip extension and using the hips as drivers for propulsion. It's also one of the easiest movements to coach considering it's built off of a developmental pattern.

You can use several different types of harness, I chose this one for the video as it's the most popular among gyms. Just make sure for this types that the chain goes through your legs rather than behind. With it set up as shown, it'll give fairly personal feedback for when the pelvis starts to tuck or if spinal flexion starts to appear(especially for guys).

To perform, start as shown in quadruped position with a band hooked to your harness. Keep a tall posture and imagine you're pushing the ground behind you as you rock forward. The rock back. Done. due to it's simplicity and easiness, I like to program sets of 10-20.

This is an(especially) appropriate drill for anyone who has the following issues:

- Locks out knees before hips

- Loads the back rather than the hips

- Has a poopy ASLR and is unready for deadlifts(especially when combined with the previous drill)

- Poor body awareness

- Has lower-leg dysfunction that is affecting traditional hinge movements

Band-Resisted Hinge ISO

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZPnyLULK9Cg

This drill is a little more advanced than the previous ones. We tend to introduce this to individuals who have already been exposed to kettlebell deadlifts, but may be having some trouble with them. Or we may just want a tension exercise and to get the glutes more involved. The reasons can span on since it's been found to be such an effective movement for progressing deadlifts.

Due to your body reflexively tightening your posterior chain to protect you from falling back, you'll be hard pressed to find an exercise that causes a more effective glute contraction. Because of that, the uses for this drill are vast. But what it also does: teaches correct load/tension in the bottom of a deadlift, reinforces position, gives an opportunity to teach proper bracing mechanics, gives a safe variation for introducing isometric work into deadlifting.

To perform this, you need to have already established competency in the first drill. If someone has trouble keeping a neutral spine or cannot physically get into a proper hinge position, this IS NOT for them. To set up attach band or cable from the ground a few feet behind you, to your hip crease. With a kettlebell either in deadlift position OR a bit in front of you, grab on to it and set your back as if you're about to lift. Then hinge back into the band. It will try to pull you further back, causing your glutes to automatically turn on to prevent you from falling. Between the added weight of the bell and the tension you've created, you will feel your strong and stable position. You will know a client has reached the appropriate spot once their shoulder are over their feet.

Again, I want to reiterate that the bell can be in front of you rather than in deadlift position. Most people starting off will need it to be in front and that's ok. I've yet to see a correlation between the position of the bell for this drill and poor carryover to deadlifting. The main component is the main position of the hips and torso. You can even see my toes start to elevate, meaning that I probably should've had it a little further in front.

This can be tricky to coach, but it's been extremely effective. Just make sure that: the arms are long, the back is flat, the shoulders end up over the feet in a hinge position and the client stays tight. I like to use the cue, "attach yourself to the bell then pry your hips into position so that the band can't move you." I also make them hold a brace in this position to help prep them for once they lift heavy.

This drill is appropriate for anyone who has the following issues:

- Poor set up

- Looses tension on initiating the pull

- Has trouble loading the hips

- Poor bracing

Band Resisted KB Deadlift

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0uHFeR55Su0

This drill is just a dynamic variation of the previous one. I find that many clients will have a great first rep, then will get, "quaddy" when lowering the weight, putting them in poor position at the bottom and killing the smooth transition to the next rep. This drill helps to keep them honest and remind them to load the hips through both portions of the lift.

You'll notice that I start the movement from the top and allow the band to assist in pulling me into position. This is because some people may have trouble finding the initial pull position at the bottom with the band constantly pulling them back(the same reason why I said some people will want the KB in front of them for the ISO). Starting from the top diminishes that issue so long as the 5lb plate is there. to guide them where to put the bell. The band helps to establish a RNT(reflexive neuromuscular training) effect which will keep the glutes involved through the entirety of the lift.

This drill is appropriate for anyone who has the following issues:

- sagital knee translation during lift

- poor eccentric phase

- hamstring dominance

Part 4: Off-Season Periodization

The Triathlete Strength Training PrimerPart 4: Off-Season Periodization

Last week we identified a couple of areas that most triathlete’s should work on improving during their off-season strength training programs. Let’s take a minute to recap what we learned in last week’s blog.

Potential Areas of Improvement

We want to use weight training as a means to…

- Fix muscle imbalances or postural issues caused by high-volume endurance training.

- Develop power and strength.

- Develop dynamic core strength and stability.

- Improve joint stability, muscle coordination, and total body awareness (proprioception).

Now let me preface this article by saying that there are many different ways to go about structuring a weight training program. Different coaches utilize different methods to achieve similar goals. The important thing to remember is that the method you choose should be based on sound logic and proven training principles. There is no right or wrong way, however, the coach or athlete who will improve the most is the one who pays careful attention to the results their current method produces. A successful coach or athlete will note the strengths and the shortcomings of a particular program, and find a way to improve upon it in the next cycle.

To add to the confusion, an Ironman-distance racer needs to spend more time developing his aerobic capacity (endurance) then someone who races sprint-distance races. The sprint-distance athlete will need to possess a strong aerobic base, but the shorter race times (sub 60-min for faster triathletes) allow for a faster pace to be held. Because of this, they would be advised to spend additional time developing other performance measures, such as their anaerobic power, capacity, muscular strength, and rate of force development. Let’s take a quick second to define these performance measures.

- Anaerobic Power: The ability to generate as much force as you can as fast as possible. This has a lot to do with your rate of force production.

- Anaerobic Capacity: The ability to sustain a high rate of force over a period of time

- Muscular Strength: The maximum amount of force a muscle or muscle group can produce in one burst.

- Rate of Force Development (RFD): A measurement of how quickly one can reach peak levels of force output. (Read all about RFD here!)

Now on to the meat…

Joe Friel recommends splitting the preparatory period into two halves. The first half can be referred to as the “General Preparation Phase” to be followed up by the “Specific Preparation Phase.” It’s a tried and true method used by triathletes all over the world, and one we can adapt to our strength training program.

The General Preparation Phase

This would be the time to implement training blocks specifically designed to increase muscular strength and anaerobic power. The sprint-distance triathlete will spend more time focusing on these parameters and will be able to implement a more comprehensive strength/power-block into their training plan. Multi-joint, compound movements will need to be a staple of your program during this time of year. The focus should be on gradually increasing the weights used over time when we’re working to improve max strength, and moving moderate to heavy weights very quickly when our focus is on achieving improvements in power.

At SAPT we’ll have our athletes squat, deadlift, row, as well as perform push-up and pull-up variations to increase their strength. Kettlebells, jumping variations and medicine balls are useful for improving anaerobic power and rate of force production. We’ll program swings, throws, and slams to increase these performance measures, as well as use the prowler and crawl variations for conditioning purposes.

A Half-Iron and Full-Ironman athlete would be well advised to dedicate time to strength and power training. Your in-season training has turned you into an endurance workhorse, but it's difficult to keep the same levels of strength you had before you turned to higher volume running. Decreased strength can lead to minor joint issues that result from a lack of stability. Implementing a strength base can reverse this process. The higher intensities (heavier weights) will provide a stimulus your body is not used to, and stimulate increases in bone density, joint stability, and strength. Of course, these athletes rely almost entirely on their aerobic endurance and at the end of the day, increasing their maximum strength will only pay off up to a certain point. These athletes will want to spend more time utilizing exercises that will improve their postural dysfunctions. Single-Leg RDLs, Turkish get-ups, and rolls variations should all be part of your repertoire.

The Specific Preparation Phase

The Specific Preparation Phase would occur next. A properly implemented Gen. Prep. phase will have improved the development of our nervous system, increased our hormone production, bone density, connective tissue strength, and fast-twitch fiber size. This next phase will focus on further improving our rate of force production and stuffing our now-massive fast-twitch fibers with mitochondria (energy-producing organelles). This way we're capitalizing on our increased anaerobic power from last phase by shifting our focus towards increasing their capacity. Methods that achieve this cause an increase in the anaerobic enzyme content in the fibers and they become more efficient. We can now use our fast-twitch fibers for longer periods of time, and push higher intensities as a result. Think how fast you could be if you truly harnessed the ability of your fast-twitch fibers.

We’ll use different methods to achieve these goals. When we’re working on aerobic and anaerobic capacity, we’ll use methods such as the HICT Method (read about it here) or Lactic Capacity Intervals. Lactic Capacity Intervals can take many forms, but the important thing is that we’re training our body to buffer the mechanisms of fatigue and increase our ability to prolong ATP production through anaerobic means. We’re teaching our body to prolong the use of our fast-twitch fibers and increasing the amount of time we can large forces (which leads to faster, more ballistic running, and an improved ability to tackle a big hill.) Near the end of this phase, when we’re getting as specific to our competitive event as possible, is when we’ll shift our focus to developing our aerobic endurance and slow-twitch fiber performance. We’ll shift to Tempo-style training for our main lifts (think barbell work), and higher rep sets that focus more on improving local muscular endurance.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vSejY4Cl47M

Wrapping Up

As I mentioned previously, this is only one way to approach off-season strength training for the triathlete. However, this method can be very effective at increasing your performance and is based off of solid training principles such as progressive overload and specificity, and is set up in a way to maximize performance benefits and build off of the previous block. In next week’s post, I will detail out a small sample program that follows this method. See you then!

The Triathlete Strength Training Primer

Part 1: An Intro to Periodization - Seeing the Bigger Picture Part 2: The Repetition Maximum Continuum Part 3: The Preparatory Period a.ka. the Off-Season Part 4: Off-Season Periodization Part 5: Off-Season Periodization, cont. Part 6: The First Transition Period Part 7: The First Transition Period, cont. Part 8: The Competition Period - In-Season Strength Training Part 9: In-Season Template Part 10: Post- Season Training

Go Catch Your Z's

By now it’s likely that the importance of getting enough sleephas been beaten into your brain. This is obviously not up for debate as you can more than likely recall a few sleep deprived afternoons in a vivid fashion. Let’s take a look at the world of napping and how they can benefit our lives and training. But not just any nap . . . . . The Power Nap. Babies and elderly people are great at napping but might this skill be beneficial to all age groups?

These days most people divide their 24 hours into the “sleeping portion” and the “awake portion” and this has worked great for a very long time. The problem is many are increasing their awake portion of the day and have tipped the balance towards sleep deprivation. Taking a nap won’t make up for low quality night-time sleeping, but a 20-30 minute nap can help improve your mood, alertness, and performance. Shorter naps work best for reaping these benefits as any longer will usually leave you feeling groggy and sluggish.

Aside from time, another key factor for optimal naps will be your environment: a room with a comfortable climate and minimal lighting will do wonderfully. You also want to reduce the amount of external noise. Napping is also a fantastic way to save your hard earned money. Instead of buying expensive drink at Starbucks or Red Bulls why not get some energy the old fashioned way?

On the research end of things, NASA performed a study looking at the effects that a 40 minute nap had on pilots and astronauts and found that performance went up by 34% while alertness rose by 100%. You may not need to navigate a shuttle around the solar system but why not use a nap to prosper in your office or next competition? D Wade loves naps.

Awesome Athlete Updates

A few cool updates: 1. Huge congratulations to Soolmaz Abooali!

We posted last week on our Facebook page that she competed in 17th World Traditional Karate-Do Championship in Geneva. She dominated and took 4th! She is 4th in the WORLD. That's pretty stinkin' awesome and we're super proud of her and are looking forward to when she conquers the 18th World Championship!

2. Victoria nailed her first bodyweight chin-up two weeks ago and I thought I'd share it.

Victoria worked hard all summer and has improved in more ways that just the chin-up department. It's always a huge encouragement to me when our female athletes rock it in the weight room and attack their workouts with vigor.

3. 2 of our baseball boys committed to colleges recently. Mitch Blackstone committed to Cornell, and Shane Russell to Lynchburg. Great job guys!

4. There is a powerlifting meet in mid-December. We have multiple people from SAPT competing: Conrad Mann, Ron Reed, Matt Gerald, Mike Snowden (SAPT's own coach), and Amanda Santiago (who is killin' her meet prep and destroying her old maxes.) Come out and support us!

That's all for now, though I'm sure we'll have more in the next month!

Rate of Force Development: What It Is and Why You Should Care

No, sorry, this is not a post on how to become a Jedi by increasing your rate of using the Force. Shucks.

The Rate of Force Development (RFD) we're going to talk about is that of muscles and is *kinda* important (read: essential to athletic performance). Today's post will enlighten you as to what RFD is and why one should pay attention to it. Next post will be how to train to increase RFD. So grab something delightful to munch on (preferably something that enhances brain function, like berries.) Caveat: There is a lot of information and other stuff that I’m not putting into this post, sorry, this is just a basic overview of why RFD is important for everyone.

What is RFD?

It is a measurement of how quickly one can reach peak levels of force output. Or to put it another way, it’s the time it takes a muscle(s) to produce maximum amount of force.

For example, a successful shot put throw results when the shot putter can exert the most force, preferably maximal, upon the shot in order to launch it as far as humanly possible. She has a window of less than a second to produce that high force from when she initiates the push to when it's released from her hand. Therefore, it is imperative that the shot putter possess a high rate of force development.

Where does RFD come from?

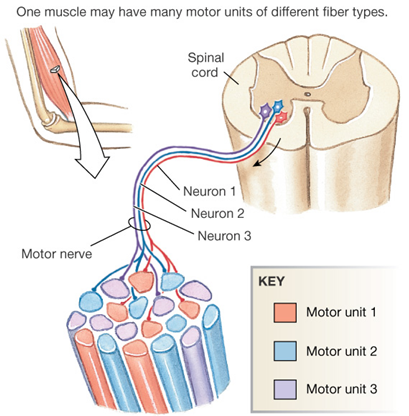

Well, let me introduce you to a little somethin’ called a motor unit. Motor units (MU) are a motor neuron (the nerve from your brain) and all the muscle fibers it enervates. It can be anywhere from a 1:10 (neuron:fiber) ratio for say eyeball muscles, which have to produce very fine, accurate movements. Or 1:100 ratio of say a quad muscle which produce large, global movements.

There are two main types of MUs: low threshold and high threshold. The low threshold units produce less force per stimulus than the high units. For example, a low unit would be found in the postural muscles as they are always “on” producing low levels of force to maintain posture. A high unit would be in the glutes, to produce enough force to swing a heavy bell or a baseball bat (even though the bat is light, the batter has to move that thing supa fast in order to smack a home run).

Also note the different stimuli required for the different units: small posture adjustments vs. a powerful hip movement. A low stimulus activates low threshold units and a high stimulus activates the high units.

Now, MUs are not exclusively low or high; MUs throughout the body are more like a ladder, low MUS at the bottom, with each successive rung being a higher threshold MU than the one below. And, like a ladder, you can just all of the sudden find yourself at the top of the ladder without having to climb the lower rungs. Unless of course, you’re a cat:

High MUs rarely (if ever) activate without the lower MUs activating first. So, the rate of force development is dependent upon how quickly the lower rungs of the MU ladder can be turned on to reach the highest threshold units (which produce the most force per contraction)… Not only that, but all those units working together produce more force than just the higher ones by themselves, so it's a good thing that the lower ones must activate too. The muscular force produced is the sum of all the motor units.

Why Care About RFD?

Since those higher threshold units won’t be active until the lower ones are on, force production will remain low until the higher ones can get their rears in gear, therefore, going up the MU ladder faster will result in more force produced sooner in any sort of movement.

Let’s take the example of two lifters, A and B. Both are capable of producing enough force to deadlift 400lbs. However, lifter A has a higher RFD than lifter B. Lifter A can produce enough force to get the bar off the ground in about 2 seconds and lock out (complete the lift) in about 3-4 seconds. Lifter B takes 3 seconds to get the bar off the floor and another 5 to get it near his knees. For those who don't know, a deadlift should be roughly 4-5 seconds TOTAL (typically, most people's muscles give out around then if the lift hasn't been completed). B-Man is going to fail the lift before he gets that bar to lock out and will hate deadlifting forever. Bummer.

Or, utilizing a Harry Potter for my analogy for this post, it is analogous to the rate of spell development; how quickly and how powerfully a wizard's spell is performed. In a duel, the faster and more forceful wizard will win. For example, when Professor Snape totally pwns Gilderoy Lockhart:

Hence, if one wants to get stronger, increasing the rate of force development is essential! Moving heavy weights is good (and high RFD helps with that as we saw with Lifters A and B from above); moving heavy weights FAST is even better when it comes to stimulating protein synthesis aka: muscle building. Possessing a high RFD is vital in order to move those bad boys quickly.

Next post, we’ll delve into training methods that can help increase the RFD so you won’t be these guys and skip deadlifting because your rate of force development is less than stellar…

The “Toes Up” Cue for Squatting and Hinging: Why I give it a thumbs down.

It’s not unusual to hear some coaches or trainers cue their clients to lift their toes when squatting. I actually used to use it fairly frequently if I had someone who couldn’t get their weight back. That is until I started looking a little more closely at what was going on with this cue. First to really understand the mechanisms at play, I want you to stand up with your shoes off. Now shift your weight back without using your hips. Did you feel your toes leave the ground? You just compensated. You pushed your weight back without using your posterior chain. So what is it that is happening when you squat toes to the sky? You are building an exercise off a compensation, and here are several reasons that you shouldn’t do that.

**Quick Disclaimer**

I do know some VERY strong people who can squat some impressive loads and their big toes do not touch the floor. It it a compensation? Yes. Do they make it work? Yes, but squatting and deadlifting are their sport. It may have been drilled into them long ago and they make it work FOR THEIR SPORT. Most of the athletes at SAPT are not training to get better at powerlifting. They are training to get bigger, stronger and faster in their area(s) of competition. It's for that reason that we must look at the bigger picture of what is going on in the exercises that we coach and their carryover to the athlete's movements.

Movement Carryover:

When deciding what movement to train in a program, you should always keep in mind the exercise's carryover to your goal. This is why squatting and deadlifting are so highly used in a strength and conditioning program. They carry over to almost everything; that is, unless they are performed incorrectly.

If you must lift your toes in order to complete a perfect squat or hinge, then there is something wrong. If you watch someone move who has trained with their toes up, what you’ll see is that everything falls apart the second those toes are cued to stay on the ground for the movement. They become less balanced, their joint positions change, and they get a bewildered look on their face as their once-thought perfect form tanks like Kevin Costner’s career after WaterWorld.

If the movement is totally dependent upon the toe extensors being engaged to function, then what movements can it possibly carryover to? Only ones where the toes are extended. Which is RARE in the athletic realm. Even worse is if the movement starts to transfer to propulsion patterns and the toes flare excessively at inopportune times. This would (and has) decrease ground contact of the foot and could hinder ankle stability.

Affects on Heel Strike:

Building off of what I said about movement carry over, deadlifting with your toes up could potentially negatively impact your gait. As we all know, a deadlift trains hip extension. If we deadlift heavy (as we should) then the movement becomes more engrained. Once it’s been engrained enough, it will start to be replicated in other activities that may require hip extension. If your toe extensors are dominant in your deadlift pattern, then it could possibly become a relationship with your heel strike.

When we heel strike in gait, there is a specific system of muscles that are supposed to fire in sequence to help with the force absorption up the chain. These muscles are the peroneals, bicep femoris, external rotators of the femur, glutes, contralateral erector spinae and contralateral rhomboids. To put it simply, muscles of the outer calf, hamstring, hip extensors and back all fire at once to help the heel strike and lead into hip extension of that leg. You can even see how the foot absorbs the force of this phase below.

Observe how the force has a drastic increase when the heel lands, but then actually decreases as the foot pronates (job of the peroneals) and then reaches a steady, controlled arc through the contact phase. Also notice how the foot whips into position after the initial heel contact and the toes reactively hug the ground.

Now imagine that there is an excess in toe extension due to compensation of the posterior chain in hip extension. This is going to cause more dorsiflexion which would in turn cause the heel to strike the ground in more acute angle, making the force sharper. Not only that, but if it is the big toe extensor (extensor hallucis longus) that becomes one of the drivers for this movement, then it can reciprocally inhibit (turn off) the peroneals, which as I said before, are crucial in the force absorption of this particular phase of gait.

Does this sound far fetched just from one small cue? It’s not. In fact many people may already have this relationship from the get-go due to a weak posterior chain and you’ve probably seen it before. Or maybe I should say that you’ve probably heard it before. Think about people who you can hear pounding the floor as they jog. Watch them walk barefoot, you will see the toes do some funky things. Watch them shift their weight back, you’ll see it again. This relationship can have huge effects on the force closure of many different joints and can be a large player in shin splints or even S.I. Joint dysfunction. This is why we, as movement professionals, must do our best to keep these systems functioning and NOT give them means to create compensation.

So instead of taking the easy route and cueing, "toes up," try the effective route and progress your clients through proper hip mechanics via activation and weight shift drills. It may take longer, but the pay off will be worth it.