Why Train In-Season?: Strength and Power Gains

Hopefully by now, you've read about the signs and reversal of overtraining. Now let's look at why and how to train intelligently in-season. A well-designed in-season program should a) prevent overtraining and b) improve strength and power (for younger/inexperienced athletes) or maintain strength and power (older/more experienced lifters).

First off, why even bother training during the season?

1. Athletes will be stronger at the end of the season (arguably the most important part) than they were at the beginning (and stronger than their non-training competition).

2. Off-season training gains will be much easier to acquire. The first 4 weeks or so of off-season training won't be "playing catch-up" from all the strength lost during a long season bereft of iron.

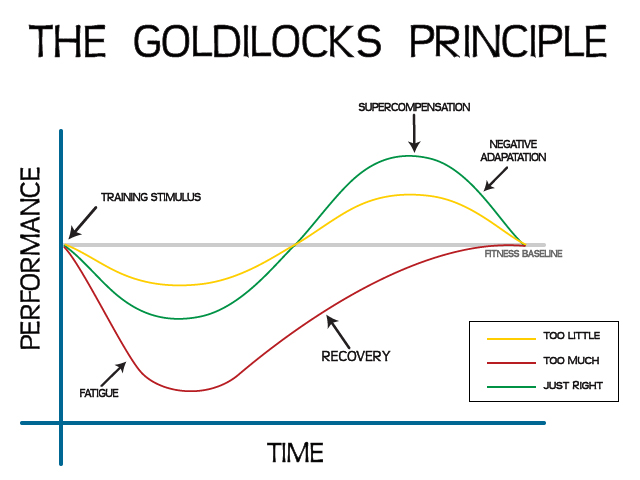

I know that most high school (at least in the uber-competitive Northern VA region) teams require in-season training for their athletes. Excellent! However, many coaches miss the mark with the goal of the in-season training program. (Remember that whole "over training" thing?) Coaches need to keep in mind the stress of practice, games, and conditioning sessions when designing their team's training in the weight room. 2x/week with 40-60 minute lifts should be about right for most sports. Coaches have to hit the "sweet spot" of just enough intensity to illicit strength gains, but not TOO much that it inhibits recovery and negatively affects performance.

The weight training portion of the in-season program should not take away from the technical practices and sport specific. Here are a couple of things to keep in mind about the program, it should:

1. Lower volume, higher intensity-- this looks like working up to 1-2 top sets of the big lifts (squat or deadlift or Olympic lift), while maintaining 3-4 sets of accessory work. The rep range for the big lifts should be between 3-5 reps, varied throughout the season. The total reps for accessory work will vary depending on the exercise, but staying within 18-25 total reps (for harder work) is a stellar range. Burn outs aren't necessary.

2. Focused on compound lifts and total body workouts-- Compound lifts offer more bang-for-your buck with limited time in the weight room. Total body workouts ensure that the big muscles are hit frequently enough to create an adaptive response, but spread out the stress enough to allow for recovery. Note: the volume for the compound lifts must be low seeing as they are the most neurally intensive. If an athlete can't recover neurally, that can lead to decreased performance at best, injuries at worst.

3. Minimize soreness/injury-- Negatives are cool, but they also cause a lot of soreness. If the players are expected to improve on the technical side of their sport (aka, in practice) being too sore to perform well defeats the purpose doesn't it? Another aspect is changing exercises or progressing too quickly throughout the program. The athletes should have time to learn and improve on exercises before changing them just for the sake of changing them. Usually new exercises leave behind the present of soreness too, so allowing for adaptation minimizes that.

4. Realizing the different demands and stresses based on position -- For example, quarterbacks and linemen have very different stresses/demands. Catchers and pitches, midfields and goalies, sprinters and throwers; each sport has specific metabolic and strength demands and within each sport, the various positions have their unique needs too. A coach must take into account both sides for each of their positional players.

5. Must be adaptable --- This is more for the experienced and older athletes who's strength "tank" is more full than the younger kids. The program must be adaptable for the days when the athlete(s) is just beat down and needs to recover. Taking down the weight or omitting an exercise or two is a good way to allow for recovery without missing a training session.

A lot to think about huh? As a coach, I encourage you to ask yourself if you're keeping these in mind as you take your players through their training. Athletes: I encourage you to examine what your coach is doing; does it seem safe, logical, and beneficial based on the criteria listed above? If not, talk to your coach about your concerns or (shameless plug here, sorry), come see us.

Overtraining Part 2: Correcting and Avoiding Future Poopiness

In the last post, we went over some symptoms of overtraining. If you found yourself nodding along in agreement (ESPECIALLY, coaches, if you noticed those symptoms in your athletes!), then today’s post is certainly for you. If you didn’t, well, it’s still beneficial to read this to ensure you, or your athletes, don’t end up nodding in agreement in the future.

Just so we’re clear, overtraining is, loosely defined, as an accumulation of stress (both training and non-training) that leads to decreases in performance as well as mental and physical symptoms that can take months to recover from. Read that last bit again, M.O.N.T.H.S. Just because you take a couple days off does NOT mean the body is ready to go again. The time it takes to recover from and return to normal performance will depend on how far into the realm of overtraining you’ve managed to push yourself.

Let’s talk about recovery strategies. Of the many symptoms that can appear, chronic inflammation seems to be a biggie. Whether that’s inflammation of your joints, ligaments, tendons, or muscles, doesn’t matter; too much inflammation compromises your ability to function. (A little inflammation is ok as it jumpstarts the recovery process.) Just as you create a training plan, healing after overtraining requires a recovery plan.

Step 1: Seek to reduce inflammation. How?

- Get plenty of sleep. Your body restores itself during the night. It releases anabolic hormones (building hormones) such as growth hormone (clever name) and the reduction of catabolic (breaking down) hormones such as cortisol. Since increased levels of coritsol are part of the overtrained symptom list, it would be a good thing to get those levels under control! Teenagers: I know it's cool to stay up late, but seriously, get your butts in bed! Not only are you growing (which requires sleep) but the sport season entails enough physical stress that if you don't sleep enough (8-10 solid hours), your body will be pissed off pretty darn quick.

- Eat whole foods. Particularly load up on vegetables (such as dark greens) and fruits (like berries) that are rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds. Solid protein sources like fatty fish, chicken breast, and lean beef (grass-fed if you can get it) will not only help provide the much-needed protein for muscle rebuilding but also will supply healthy fats that also help reduce inflammation. Speaking of fats, adding coconut milk/oil to smoothies as an excellent way to ingest some delightful anti-inflammatory fats.

- Drink lots of water. (not Gatorade or powerade or any other -ade.) Water helps the body flush toxins, damaged tissues/cells, and keeps the body’s systems running smoothly. Water also lubricates your joints, which if they’re beat up already, the extra hydration will help them feel better and repair more quickly. A good goal is half your body weight in ounces.

Step 2: Take a week off

You’re muscles are not going shrivel up, lose your skill/speed, nor will your body swell up with fat. Take 5-7 days and just rejuvenate. Go for a couple walks, do mobility circuits, play a pick-up basketball game… do something that’s NOT your normal training routine and just let your body rest. Remember, the further you wade into the murky waters of overtraining, the longer it will take to slog your way out. During the sports season, this isn't always an option. In that case, coaches, give your players a couple of "easy" practices/workouts with the goal of getting the blood flowing, but not destroying the athletes. They should walk away feeling better than when they started. Building in an "easy" practice each week would go a long way in preventing overtraining.

Step 3: Learn from your mistakes.

While you’re taking your break, examine what pushed you over the edge. Was it the volume or intensity too high (or both?), too many days without rest? Was your mileage too high? Were you were stressed out at work/school, not sleeping enough, or maybe you weren’t eating enough or the right foods to support your activity. Are there external factors you’re missing? For instance, I’ve learned that I cannot train too hard (outdoors especially) during allergy season. Even if I'm inside, I just can’t get enough oxygen in my system to support intense training (lifting or sprinting). Therefore, I limit my outdoor sprints, ensure I take longer rest breaks between sets, and make sure I take medication during the peak of the spring and summer.

Step 4: Recalculate and execute

When you’re ready to come back, don’t be a ninny and do exactly what you were doing that got you into this mess in the first place. Hopefully, you learned from your mistake and you’ll make the necessary changes to avoid overtraining in the first place. Here, let’s learn from my mistake:

I overtrained; and I mean, I really overtrained. I had all the symptoms (mental and physical) for months and months. I was a walking ball of inflammation, every joint hurt, I was exhausted mentally and physically (and, decided to make up for my exhaustion by pushing myself even harder.) I ignored all the warning signs. This intentional stupidity led to my now permanent injuries (torn labrums in both hips, one collapsed disc in my spine, and two bulging discs). The body is pretty resilient, but it can only take so much. I ended up taking four months off, completely, from any activity beyond long walks. (that sucked by the way). When I did come back, I had to ease into it. Very. Very. Slowly. Even then, I think I pushed it a bit too much. It took me almost 2 years to return to my normal physical and mental state. (Well, outside of the permanent injuries. Those I just work around now.) Learn from my mistake. Overtraining is not something to poo-poo as "weakness" or "just being tired." It's real and can have damaging, lasting effects.

So how can we avoid overtraining? Here are simple strategies:

1. Eat enough and the right foods to support your activities.

2. Take rest days. Listen to your body. If you need to rest, rest. If you need to scale back your workout, do so.

3. Keep workouts on the shorter side. Don’t do marathon weight lifting sessions. Keep it to 1-1.5 hours. Max. Sprint sessions shouldn’t exceed 15-20 minutes. (if you're in-season, weight lifting sessions should be 45 min-1 hour MAX, with lower volume than out-of-season)

4. Sleep. High quality sleep should be a priority in your life. If it isn’t, you need to change that.

5. Stay on top of your SMR and mobility work. I wrote about SMR here and here.

6. Train towards specific goals. You can’t be a marathon runner and a power lifter. Pick one to three goals (that don’t conflict with each other) and train towards them. You can’t do everything at once.

Armed with the knowledge of overtraining prevention, rest, recover, and continue in greatness!

Overtraining Part 1: Symptoms

This month's theme is in-season training since the spring sports are starting up. All the practices, games, and tournaments start to add up to over time, not to mention any weight room sessions the coachs' require of their athletes. Lack of proper awareness and management of physical stressors can lead, very quickly in some cases, to overtraining... which leads to poor performance, lost games, increase risk of injury, and a rather unpleasant season.

The subject of overtraining is a vast one and we won't be able to cover all the aspects that contribute, but by the end of this two part series, you should have a decent grasp on what overtraining is and how to avoid it. Today's post will be about recognizing the symptoms of overtraining while next post will offer techniques and training advice to avoid the dreaded state of overtrained-ness. (Yes, I made that word up.) Li'l food for thought: quite often the strength and conditioning aspect of in-season training is the cornerstone of maintaing the health of the athlete. Too much, and the athlete breaks, but administered intelligently, a strength program can restore an athlete's body and enhance overall performance. Right, let's dive in!

Who doesn’t like a good work out? Who doesn’t like to train hard, pwn some weight (or mileage if you’re a distance person), and accomplish the physical goals you’ve set for yourself? Every work out leave you gasping, dead-tired, and wiped out, otherwise it doesn't count, right? (read the truth to that fallacy here)

We all want a to feel like you've conquered something, I know I do!

However, sadly, there can be too much of a good thing. We may be superheroes in our minds, but sometimes our bodies see it differently. Outside of the genetic freaks out there who can hit their training hard day after day (I’m a bit envious…), most of us will reach a point where we enter the realm of overtraining. I should note, that for many competitive athletes (college, elite, and professional levels) there is a constant state of overtraining, but it’s closely monitored. But, this post is designed for the rest of us.

Now, everyone is different and not everyone will experience every symptom or perhaps experience it in varying degrees depending on training age, other life factors, and type of training. These are merely general symptoms that both athletes and coaches should keep a sharp eye out for.

Symptoms:

1. Repeated failure to complete/recover in a normal workout- I’m not talking about a failed rep attempt or performing an exercise to failure. This is a routine training session that you’re dragging through and you either can’t finish it or your recovery time between sets is way longer than usual. For distance trainees, this may manifest as slower pace, your normal milage seems way harder than usual, or your heart rate is higher than usual during your workout. Coaches: are you players dragging, taking longer breaks, or just looking sluggish? Especially if this is unusual behavior, they're not being lazy; it might be they've reached stress levels that exceed their abilities to recover.

2. Lifters/power athletes (baseball, football, soccer, non-distance track, and nearly all field sports): inability to relax or sleep well at night- Overtraining in power athletes or lifters results in an overactive sympathetic nervous response (the “fight or flight” system). If you’re restless (when you’re supposed to be resting), unable to sleep well, have an elevated resting heart rate, or have an inability to focus (even during training or practice), those are signs that your sympathetic nervous system is on overdrive. It’s your body’s response to being in a constantly stressful situation, like training, that it just stays in the sympathetic state.

3. Endurance athletes (distance runners, swimmers, and bikers): fatigue, sluggish, and weak feeling- Endurance athletes experience parasympathetic overdrive (the “rest and digest” system). Symptoms include elevated cortisol (a stress hormone that isn’t bad, but shouldn’t be at chronically high levels), decreased testosterone levels (more noticeable in males), increase fat storage or inability to lose fat, or chronic fatigue (mental and physical).

4. Body composition shifts away from leanness- Despite training hard and eating well, you’re either not able to lose body fat, or worse, you start to gain what you previously lost. Overtrained individuals typically have elevated cortisol levels (for both kinds of athletes). Cortisol, among other things, increases insulin resistance which, when this is the chronic metabolic state, promotes fat storage and inhibits fat loss.

5. Sore/painful joints, bones, or limbs- Does the thought of walking up stairs make you groan with the anticipated creaky achy-ness you’re about to experience? If so, you’re probably over training. Whether it be with weights or endurance training, you’re body is taking a beating and if it doesn’t have adequate recovery time, that’s when tendiosis, tendoitis, bursitis, and all the other -itis-es start to set in. The joints, muscles, tendons, and ligaments are chronicallyinflamed and that equals pain. Maybe it’s not pain (yet) but your muscles feel heavy and achy. It might be a good time to rethink you’re training routine…

6. Getting sick more often- Maybe not the flu, but perhaps the sniffles, a sore throat, or a fever here and there; these are signs your immune system is depressed. This can be a sneaky one especially if you eat right (as in lots of kale), sleep enough, and drink plenty of water (I’m doing all the right things! Why am I sick??). Training is a stress on the system and any hard training session will depress the immune system for a bit afterwards. Not a big deal if you’re able to recover after each training session… but if you’re overtraining, the body never gets it's much-needed recovery time. Hence, a chronically depressed immune system… and that’s why you have a cold for the 8th time in two months.

7. You feel like garbage- You know the feeling: run down, sluggish, not excited to train… NOOOOO!!!!! Training regularly, along with eating well and sleeping enough, should make you feel great. However, if you feel like crap… something is wrong.

Those are some of the basic signs of overtraining. There are more, especially as an athlete drifts further and further down the path of fatigue, but these are the initial warning signs the body gives to tell you to stop what you’re doing or bad things will happen.

Next time, we’ll discuss ways to prevent and treat overtraining.

March Madness: In-Season Training

Ah, the spring! (well, it would be if it wasn't snowing so much here in D.C.!) This means that the spring sports are ramping up. Schedules get tighter, days get longer, and the body takes a beating.

This month SAPT is going to provide stellar reasons why every athlete should continue their strength training in-season. Some of these include (but are not limited to):

- Prevention of strength and power decreases (both of which are rather important, especially during the end of the season during the play-offs. No good to be weak and slow!)

- Increase strength and power (see above reason)

- Prevention of over-use injuries. (How many times did you throw that ball today?)

- Mental breaks (ah, brain can relax.)

All that plus a super special guest post JUST for coaches.

Check back later this week as we get rolling into a healthy, strong, and successful season!

Guest Post: Speed and Agility Development by Goose

So you want to run like this guy!

But you feel like this guy?

No need to freak out, here are a couple of tips to get you running lightning fast!

1. Conditioning

If you slack on your conditioning it doesn’t matter how fast you can run. You’ll be pooped out after one play and rock the bench for the rest of the game! Here are some suggestions, as well as a link, to get your conditioning game on par:

-Sled Workouts

-Track Workouts

Any conditioning work you do should be focused on maintaining a fast speed for a 15-30 seconds time span. A strong conditioning base is imperative as the game comprises of repeated quick all out bursts of speed for a long time. Keep this in mind when designing your workouts and the role rest plays in said workout.

2. Acceleration

Once your conditioning and strength training needs are met, now it’s time for the fun! Acceleration work should focus on improving your ability to reach your top speed as fast as possible. If you’re a running back, wide receiver, linebacker, or safety you’ll be more efficient at your job if you can reach top speed within 15-20 yards rather than 25-30 yards. Here are some suggestions on how to improve acceleration:

-Downhill Running (Use a slight downhill)

All three of these drills force quicker turn over (how fast your feet hit the ground) and/or exert high amounts of force on the ground. Both are the components needed to accelerate proficiently.

3. Believe in the process!

A lot of young athletes are really eager and fired up to improve but then get discouraged when it doesn’t come fast and easy. Improving your abilities is an everyday, 24/7, 365 day grind. If you are putting in the work on the field and in the weight room, plus staying diligent with flexibility and mobility work, then result will come. (Note from Kelsey: and EAT REAL FOOD!!!) Be patient, allow your body to do its thing, and trust in your coach’s plan!

Breathing Mechanics: Why Football Players Should Care

Breathing? Really? How could something as simple and common as breathing possibly affect football performance? If you're willing to spend about eight minutes to read this, you won't be sorry! Proper breathing mechanics are an aspect of sports performance that is a) largely ignored by a decent chunk of the athletic community (but is growing in exposure thanks to the PRI, Eric Cressey, Chalrie Weingrof, Kevin Neeld, Mike Robertson and a host of other smart coaches.) and b) are the 6 Degrees to Kevin Bacon of athletic movement. Everything connects back to breathing mechanics. Note- this is going to barely scratch the surface of all the breathing literature out there, so fitness nerds, don't get uptight about missing information. The point of this article is to explain the importance if breathing mechanics and provide some practical applications for coaches and players. If this post sparks your interest and you want to learn more, I recommend a search on the Posture Restoration Institute (from which I derived most of the information); all their articles are a good starting point.

A brief anatomy lesson is needed before we proceed.

The diaphragm is an umbrella shaped muscle and when it contracts, it pushes your organs down. This creates a large space in your lungs thus lowering the pressure. The one thing I remember from physics is that air moves from high pressure to low pressure. So, when there’s a lower pressure in your lungs, air whooshes in. (ha! And you that you sucked it in. Nope, it forces itself in. This blew my mind when I first learned the secrets of inhalation.)

Diaphragms are cool and important (understatement!) but breathing requires accessory muscles too. Our intercostals (rib muscles) and scalenes and sternocleidomastoids (neck muscles) contribute to the life-giving act of breathing. We need to use ALL THREE areas.

You can test yourself to see what area you tend to rely on most often based on if you get a cramp during exercise. For example, my neck (scalenes and SCM) is hyperactive during exercise and I get neck cramps during sprint work. Got a stitch in your side? Probably relying more on intercostals than your diaphragm.

Think of it like this: Harry Potter is the diaphragm, Hermione is the intercostals, and Ron is the neck muscles (mainly because Ron is so temperamental and is easily irritated, much like the scalenes).

As a coach or player, here's a quick test of breathing mechanics. Lye supine with your knees bent at 90 degrees against a wall. Place your hands just beneath your rib cage (this helps determine if the abdomen is expanding 360 degrees during inhalation). Take a DEEEEEEEP breath and exhale.

If an athlete is breathing properly we should see three things:

1. Circumferential expansion of the the abdomen (front and back)

2. Rib expansion (front and back too)

3. Li'l bit of apical (upper ribs) elevation. Note: too often THIS is where you'll see the breathing take place. You can tell because the shoulders will rise up towards the ears.

It's when one of these areas is impaired that we see dysfunction (pain/injuries) occur. Harry Potter is awesome but he would never have defeated Voldemort if he didn’t have Ron and Hermione.

1. Breathing affects EVERYTHING. The average person takes roughly 20,000 breaths per day. That's a LOT of contractions of the diaphragm. Aberrant breathing patterns will not only alter the ability of the diaphragm to function efficiently but it creates hyperactivity and hypertonicity (high tone/tension in the muscle) of the accessory muscles AND of muscles down the line (believe it or not, it can affect hip mobility!).

2. Think about the accessory muscles (and their neighbors): scalenes, SCM, levator scapulae, pec minor, trapezius... if those guys are tight and irritated, that will wreck havoc on cervical posture and shoulder mobility and function. Why do you care about that? If the cervical posture is whacked out (aka, your neck) those muscles are not going to function properly, it'll be harder to strengthen them in the way they need it and that puts you at a greater risk for concussions. Shoulder function/mobility is especially important for quarterbacks. If the shoulder isn't moving properly, say hello to rips, tears, and strains of the rotator cuff, bicep tendons, and labrums. Hooray.

3. All that tension spreads to the rest of the body. It increases the sympathetic state (flight or fight response) and thus not allowing the body to fully recover after workouts/practices/ games. This will eventually run down the athletes. The increased sympathetic state will increase anxiety, mess with sleep patterns, and can even decrease pain threshhold; all of these equal poopy workouts and even worse recovery.

Hopefully, after all that, I've convinced you that breathing patterns, make that PROPER breathing patterns, are extremely important and integral to athletic success. Again, if you truly want to improve performance, you should see a professional and get assessed and trained. (that was a shameless plug, I know, but it's true!)

But, run through 4 quick and simple things coaches and players can add to/be cognizant of to create a better breathing environment.

1. Posture Re-education:

Why? Three words: Zone of Apposition.

"Achieving the optimal ZOA really depends on the shape/orientation of your ribcage. If your lower anterior (front) ribcage tends to be elevated (as in picture on the left), it can alter the length-tension relationship of your diaphragm resulting in aberrant breathing pattern, lumbopelvic instability (hips and spine...BAD place for instability) and a cascade of movement dysfunctions." - Bill Hartman

Read about the Zone of Apposition on PRI's website.

2. Breathing Re-Education

As mentioned above in the "what you should see" part, we need to teach our athletes (and ourselves) how to

a) Achieve circumferential expansion. This does not mean just the belly sticking out during inhalation, but we need lateral expansion too (out to the sides and back of the body). A lot of people will "hollow" that is, draw in the belly and elevate the ribs and shoulders. This needs to stop. A drill like this will help.

b) Breathe with the abdomen and chest moving at the SAME TIME. The accessory muscles (notably the neck muscles) should be relaxed. Here's a video from Bill Hartman that encompasses both points:

c) Learn to get our ribs down with a neutral spine! Too often athletes have the mega arch (lordosis) in the lower back. This needs to stop! Compare the two pictures above, see how the lower portion of the ribcage is down on the "correct" picture? This is how we need to inhale and exhale. Exhalation should be active: the abs should be involved to help pull the ribs down.

3. Coaching Breathing

We need to teach athletes how to get to a neutral spine with the ribs down. The picture of the supine breathing above is a perfect drill for that. The floor gives feedback so the athlete can feel their spine and whether or not it's neutral. It's a great way to teach a "packed neck" too (meaning, no cranking on that neck into extension). The left hand can help monitor rib position to teach the athlete what "ribs down" feels like. THIS MUST HAPPEN FIRST before we expect them to move well during more strenuous exercise. Have your athletes spend a few minutes before training breathing in proper position.

4. Breathing drills

Breathing "reps" should be 3-4 sec inhale through the nose, a 5-8 sec exhale through pursed lips with a 1-2 sec hold. A great drill is the supine 90/90 position from above. It's a low level drill that will help the athlete be successful. Here's another example:

And this one, especially for those who live in a more "extended" posture:

There are more advanced drills, but these should be enough to get your athletes rolling.

So to recap:

Breathing mechanics are important. It affects all aspects of athletic performance. Breath well.

Re-educate posture and patterns.

Breathing is important.