Summer = Off Season = TRAINING!!!

Summer is nearly upon us, spring sports are over (or nearly so), school is winding down, and the sun is waking us all up quite a bit earlier. **DEEEEEP BREATH*** I love summer.

Not only is it fantastically warm and I finally sweat profusely during my workouts (contrast that to the winter to where I'm lucky to break a sweat, in my sweat pants...I get cold pretty easily) but it's the off-season for high school sports. I know some of you play your sport year-round in clubs and stuff (see my thoughts on that HERE), but seriously, the summer is a perfect time to start training and getting stronger for next year's season.

So, it's time to hit the weight room, right? Start smashing PRs and moving heavy iron bars around, right? Not so fast, cowboy.

A huge flub athletes commit in the beginning of the off-season is training too hard, too fast. Think about it, you just spent 3, 4, even 5 months in-season with practice after practice, games, and no-so-much lifting. Your body is probably weaker (even if you trained during the in-season, it still isn't PR shattering material) and you've been performing the same, repetitive motions to the point where you've probably developed at least one sort of wacky asymmetry. For overhead athletes, they've been throwing or hitting on the same side, soccer players kick with the same leg, track athletes have been running in the same curve (to the left), and lacrosse players have been whipping their upper bodies around the same direction. Show me an athlete coming out of the season that isn't crooked somewhere (that's the technical term) and I'll show you a One Direction fan that isn't a female teenager. Oh wait, they don't exist. (if you don't know who they are, keep it that way, it isn't worth your time.)

To keep it pretty general, as the two subsequent posts will deal more with specific sport recommendations, here are some thoughts on the first 3-4 weeks of off-season training:

1. Keep the volume down- You've pounded your body all season, high volume work will only stress it out more. Stick to 15-20 reps total of your main lifts (squat, deadlift, bench, etc.) and 24-30 reps of accessory work, total. There should only be 2-4 accessory lifts and 1 main lift per workout.

2. Keep the intensity reasonable-- I'm not advocating lifting 5 lb dumbbells for everything, but again, you've pounded your body for several months, starting at 60-75% of your maxes is not a dumb thing to do. Get some quality, speedy reps in of the main lifts. For you accessory work, move weight that will get your blood flowing, but leaves some gas in the tank (a lot of gas in the tank). If you really want to burn, adding negative reps or isometric holds can increase the intensity without overloading your joints. For example, we like Bulgarian split squats with a :06 negative, or pushups with a :05 isometric hold at the bottom.

3. Take a week away for the barbell-- It's just a week, calm down, but replacing barbell squats with some goblet squats or deadlifts with some swings are excellent ways to give your body a break and still train those movements.

4. Work on tissue quality- Foam roll, use a lacrosse ball, or better yet, go see a manual therapist to dig out the nasty, knotted tissue that resides in your body. Mobility drills for the tight bits and stability drills for the loose bits should be prevalent in your workout. For example: soccer player's hips will be pretty tight and gunky, so that requires some attention to tissue quality of the glutes, quads, and TFL and mobility work. Contrast that to a baseball player's anterior shoulder (front side) of his throwing arm, that this is probably much looser than it should be, so he'll need some stability work to pull his humerus into a more neutral position.

5. Sleep a lot and eat quality food-- I bet both of these have been in short supply over the course of the season, huh? Yes, these two are SUPER important for recovery purposes as well as muscle growth. Shoot for 7-9 hours of sleep per night and load up on the vegetables!

The sole goal of the first couple weeks after the season is to restore the poor, asymmetrical, beaten-up body and allow for some recovery time. Keep the volume and intensity low to moderate, work on tissue quality and mobility as needed, and sleep! Then, and only then, mind you, can you attack the rest of your off-season like the Hulk.

Early Sport Specialization: Why This Needs to Stop (with a capital "S")

Here in northern Virginia, and in other hub-bub places too, it's not uncommon for an athlete to play a sport during the high school season, and then transition straight into the club season (which lasts f-o-r-e-v-e-r), leaving the athlete with maybe 2-3 weeks rest before try-outs for the next year's high school season start. Does this sound familiar? Does this sound healthy? Today we're going to address a growing (alarmingly so) problem with youth athletics: early sport specialization. As a strength coach, I see some messed up kids when it comes to movements, joint integrity, and muscle tissue quality (all = poop) who play year-round sports at young ages (that is, under 16-17 years old). I see year-round volleyball players who can't do a simple medicine ball side throw. Why? Because they spend ALL YEAR moving in the saggital (forward/backward) plane with a little bit of the frontal plane (side to side shuffling, but even that is dominated by their inability to actually move sideways; they tend to fall forward and/or move as if they're running forward, just facing a little bit to the side.) They have limited movement landscape (remember this?) and therefore are limited athletes.

I see young baseball players with chronic elbow or shoulder pain. Why? Because they throw a ball the same way ALL YEAR ROUND. And they're not strong enough to produce the force needed to throw it properly, (because, heaven forbid, they take some time off to actually weight train and get stronger) so they rely on their passive restraints (ligaments, tendons, and joint capsules) to throw.

This topic gets me fired up because I see SO MANY injuries and painful joints in kids who shouldn't have injuries or painful joints. I see kids who can't move like a normal human being because they're locked up and, worse, don't even have the mind-body connection to create movements other than those directly related to their chosen sport.

There's this pervasive myth that if a kid doesn't play year round or get 10,000 hours of practice, then he/she will never be a good athlete. Parents get caught up in chasing scholarships and by golly, if Jonny doesn't play travel ball he'll fall behind, then he won't make varsity, then he won't get into a good college... and on and on. My friends, we need to take a step back and think about what's best for the athlete. Do the aforementioned afflictions sound good to you?

But enough of my opinion, let's look at some hard science to support the Stop-Early-Specialization-Theory.

Playing multiple sports and playing just for the sake of running around like a kid builds a rich, diverse motor landscape, especially during the years before late adolescence. Diversifying the motor landscape, or movement map, or the bag-o-skillz, or whatever you want to call it, is essential to human development and especially valuable to athletes. I'm going to sound like a broken record, but kids need a broad and varied map to:

1. Understand how to move their bodies through space

2. Create and learn new movements

3. Learn how to adapt to their environment

4. Develop better decision making and pattern recognition based on their circumstances (i.e. being able to find the "open" players in a basketball game helps in finding one on the soccer field. )

Matter fact, this really smart fellow, Dr. John DeFirio MD, who is the President of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, Chief of the Division of Sports Medicine and Non-Operative Orthopaedics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Team Physician for the UCLA Department of Intercollegiate Athletics (that's quite the title, eh?) says this:

"With the exception of select sports such as gymnastics in which the elite competitors are very young, the best data we have would suggest that the odds of achieving elite levels with this method [early sport specialization] are exceedingly poor. In fact, some studies indicate that early specialization is less likely to result in success than participating in several sports as a youth, and then specializing at older ages"

And, Dr. DiFiori encourages youth attempt to a variety of sports and activities. He says this allows children to discover sports that they enjoy participating in, and offers them the opportunity to develop a broader array of motor skills. In addition, this may have the added benefit of limiting overuse injury and burnout.

You can read his full article here. The article also notes two studies in which NCAA Division 1 athletes and Olympic athletes were surveyed regarding what they did as children. Guess what? 88% of the NCAA athletes played 2-3 sports as kids, and 70% of them didn't specialize until after age 12. The Olympians also all averaged 2 sports as kids Are you picking up what he's putting down? Specialization doesn't make great athletes, diversification does!

Side bar: Check out Abby McCollum, who played 4 sports for a Division 1 school. The article says that she was recruited last minute... probably because she was such a great all-around athlete that she could play any sport.

Next up: injuries rates.

Dr. Neeru Jayanthi, a sports medicine physician, in conjunction with Loyola University published a few studies using a sample set of 1,026 athletes between ages 8-18 who came into the Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago for either sports physicals or treatment for sports-related injuries. The study ran from 2010 to 2013. Dr. Jayanthi and her collegues recorded 859 injuries, of which 564 of them were overuse injuries (that's well over HALF). Of those 564 injuries, 139 of them were serious injuries concerning stress fractures in the back or limbs, elbow ligaments or injuries to the cartilage. All of these injuries are debilitating and can side line and athlete for 6 months or more. The broad study is reviewed here and a more specific cohort (back injuries, which carry into later in life) is here. I highly recommend reading both as the data are eye opening.

To sum up Dr. Jayahthi and co.'s recommendations on preventing overuse injuries (I took it directly from one of the articles in case you don't have time to read them both):

• If there's pain in a high-risk area such as the lower back, elbow or shoulder, the athlete should take one day off. If pain persists, take one week off. (though I think it should be more)

• If symptoms last longer than two weeks, the athlete should be evaluated by a sports medicine physician. (and go get some strength training! There's a reason that pain is occurring; something is overworking for something else that's NOT working.)

• In racket sports, athletes should evaluate their form and strokes to limit extending their backs regularly by more than a small amount (20 degrees). (this should also apply to any overhead sport like volleyball, baseball, softball, etc.)

• Enroll in a structured injury-prevention program taught by qualified professionals. (hey, like SAPT? Lack of strength is a common denominator among injured athletes.)

• Do not spend more hours per week than your age playing sports. (Younger children are developmentally immature and may be less able to tolerate physical stress.) (10 year-olds don't need 12 hours or soccer! Also check out Dr. Jayahthi's injury prediction formula.)

• Do not spend more than twice as much time playing organized sports as you spend in gym and unorganized play. (Kids, go play tag, get on the playground, play capture the flag, anything; JUST PLAY!)

• Do not specialize in one sport before late adolescence.

• Do not play sports competitively year round. Take a break from competition for one-to-three months each year (not necessarily consecutively).

• Take at least one day off per week from training in sports.

The highlights and comments are mine. Do you see the RISK involved in specializing in a sport early in life? Not only does the risk of injury skyrocket, and the ability to move fluidly and easily plummet, but there's a lot of external pressure on the athlete to perform. Stressed athletes don't perform well. I don't know how many times I've asked my year-round players what they're doing on the weekends, it's always "tournament" or "practice." They have NO LIFE outside of sports. To me, that seems unhealthy and frankly, a recipe for burn-out.

Parents, athletes, and coaches, in light of all this research, I urge you to strongly reconsider year-round playing time for kids under 16 or 17. I urge you to allow athletes time off, to play other sports besides they're favorite, and to just be a kid. I urge you to keep the long-term development of our athletes in mind; do you want to risk a permanent injury, hatred of sport (because of burn out), or development of weird compensations and movement patterns?

Let's build strong, robust athletes that can do well in the short- and long-term instead of pigeon-holing them into a particular sport and limiting their athletic potential.

An Intro to Vision Training

Today’s Post is part 1 of a 3 part series as we tackle vision training. In this first installment, I’m going to try to explain the importance and reasoning for vision training as well as some affects that it can have on just about any task. Make sure you check back later to see the second installment that will deal with more specific scenarios for sports and the third one that will give you some drill and programming scenarios that you can use yourself. Enjoy!

For every action, there is an equal or opposite reaction. In the world of sports, this stays true between competitors. The accuracy and level of this reaction is determined by the perception, strategy and physical ability of the athlete. There are thousands upon thousands of articles written about the later two, but very few on the topic of perception and its role in the way we move and perform.

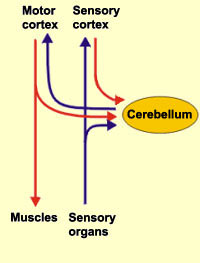

First, let’s define perception and it’s affect on the way we move. Your perceptions consist of the sensory input that your brain collects from your internal and external senses. Essentially, every movement that you have ever performed has been based off of these perceptions. Your brain collects all the different factors of your environmentthrough your sight, hearing, taste, feel, proprioception, smell, vestibular feedback(think balance) and relates them to past experiences. Based on the combination of past experience, current conditions and the task at hand, a movement is chosen and performed. An example of this would be running on wet grass. You seldom consciously think, “I better brace my movements so I don’t frickin’ eat it when I change direction.” You naturally change the length of your stride and adjust the angles appropriately. This is because your brain processed the sensory information: the feel of dampness, the sight of the glistening grass, the proprioceptive feedback of where your legs moving, the vestibular feedback of your body leaning, and the sound of feet skidding on the grass, then reflected on a past experience (probably of biting it on wet grass). It then pieced together a motor program in the cerebellum to be carried out by the body and caused you to run more carefully on the grass.

The outcome of this motor program will be more or less, “recorded” for future reference when you need to complete a similar task. Whether the task is successfully completed or not and how it made you feel, determines if the program will be closely replicated next time.

All of this is relevant to keep in mind when it comes to any type of training, but it encapsulates the whole premise of perceptual training. Perceptual training consists of helping the athlete to identify key elements in their environment to cue them on how to react with the appropriate movement.

Now you can get pretty deep in sport-specific factors that may be important in perception, but for the purpose of this installment, we are only going to look into the visual elements of general sport. For starters, a few key visual factors that will influence all sports are eye dominance, spotting and the vestibular system.

Eye Dominance

Eye dominance plays a key role in how your brain handles site. Just as you have a hand that you prefer to use, you also have an eye that prefer to see from and they may not be the same side. Because both eyes send slightly different portraits of the world, the brain chooses one that is trusts more. In this eye, images may appear clearer, more stable, larger and it has even been suggested to have perceptual processing priority. Some have even hypothesized that it can actually inhibit the sensory information from the non-dominant eye.

There are several types of dominance and honestly, it can all get pretty thick, but the key point to hold onto is that the information gathered through the dominant eye is going to be more credible, processed more quickly and may potentially affect the action taken as compared to if processed primarily through the non-dominant eye. Now there are studies that look into if cross-dominant individuals(right-handed and left-eyed) have an advantages in side-stanced skills like batting due to the closer position of the dominant eye, but they have found no relationship. This is because the stimulus is still well within the focal system of vision, just as it would be with a non-cross-dominant individual.

Now here’s where the shizz-nit gets cool for coaches. Though the athlete may not have an advantage to the dominant side of focal vision, they should theoretically have an advantage in that side’s peripheral vision. This is because the peripheral vision is dependent on the ipsilateral eye, as noted on the above diagram. If we know that one side’s ambient/peripheral vision will have a decreased response time, we can play it to our advantage This could be a game changer in where we position certain athletes.

Another important note to make is that the ambient system is largely controlled by subconscious function. So to take it a step further, you could start performing reaction-type drills within the athlete’s dominant peripheral vision so that the desired response is autonomous(done without thinking). This would help to ensure not only the decreased response time, but more desired responses. This may include drills such as setting a volleyball to a player from their dominant side just within their peripheral vision.

Spotting

No I do not mean the action of helping your bro with his bench press. The spotting I mean is the action of fixating on a particular point during a rotational movement to help reduce dizziness and keep the athlete oriented. You see this when a dancer spins, they will look to one point and keep their eyes set on that point until they are forced to reset. This serves as more of an internal cuing for the vestibular system, but it can be very important in skill acquisition and perception.

As many coaches can note, vision drives movement and wherever the eyes go, the body will follow. This is why appropriate spotting is key in a variety of movements. If the athlete fixates in the wrong position or the wrong time, they could easily throw off their movement, timing and overall performance. An athlete that seems to be over-spotting could be compensating for a vestibular issue. If that’s the case, no amount of technique work will bring that skill to fruition until their vestibular input is restored.

Just the same, there are several cases where the spotting point should be coached to help drive a skill. Think about the individuals who adjust their vision as soon as they hit a golf ball and how it affects their follow through. Or how some baseball players may prematurely look into the field when they hit and negatively affect their swing. You want them to stay fixated on a spot so that the movement can be completed smoothly without alteration of perception.

Vestibular Input

As I mentioned when reviewing spotting, the vestibular system is going to play a vital role in an athlete’s perception. The vestibular system is an internal sensory system that controls the sense of movement and balance, soooo it’s kind of a big deal. It’s largely overlooked in many training programs, especially considering it is the system that will influence EVERYTHING we do. In fact, it is so important the first sensory system to fully develop(at 5 months post conception).

The reason I am including this system in an article on visual training is that the vestibular system will rely heavily on sight for reassurance. It’s always trying to find equilibrium to keep you from falling on your face. Whereas most of the informationused for equilibrium comes from balance organs in the inner ear, it’s estimated that 20% comes from your vision. Consider the fact that most people do not regularly challenge the sensory organs in their ears(rolling around, tumbling, etc.) and yet they are almost ALWAYS using their eyes for feedback, you can see how a compensatory relationship can form.

If an athlete does have a dysfunctional vestibular system, you may see several signs: a loss of mobility when the head is no longer neutral, constant spotting, poor overall balance, etc. The easiest way to rule this out as an issue is to have them stand on one leg with their eyes closed. If they truly suck at this, THEN IT NEEDS TO BE ADDRESSED. Motor control cannot be progressed without the athlete first being able to figure out where they are at in space.

** Fun fact: Regularly working the vestibular system through activities that will work the inner ear organs will help to keep an active brain and grow new nerve cells.

Putting it together

With these factors in mind, I coach can easily address vision training on the field or in the weight room. Knowing an athlete’s eye dominance, when they should be spotting and when their vestibular system is the limiting factor are all HUGE factors of performance. Being able to incorporate the appropriate drills and strategies to match these needs can easily take your athletes to the next level. My next installment will include more sport-specific and task-oriented elements that will help you to take your drills a step further and have your athletes a step ahead of the game.

Movement + Young Kids = Successful Athletes

Today"s guest post is SAPT"s Mike Snowden, Intern Extraordinaire!

Today’s post carries on this month’s idea of training for youngsters. In previous posts we’ve seen how strength training can benefit this population and now we will discuss how movement plays a critical role in a child’s development. Brain development research has shown that humans possess a “window of opportunity” where sensory and movement experiences are necessary. These experiences play a unique part in the social, emotional, spatial awareness, sensory-motor, language, and cognitive skill progress of a child. For the development of skills, this “window of opportunity” is open from before birth to around age 7 and it begins to narrow with age. Experiences during this period are vital in laying the foundation of a person’s motor control skills.

So how can you help a youngster, you might ask?

- Give children lots of sensory-motor experiences, especially of the visual-motor variety.

- Example: Having kids strike, kick, throw, bounce, and catch balls or soft objects of different sizes and shapes with both sides of their body.

- Have your child perform an assortment of gross motor activities involving locomotion, postural regulation, and coordination.

- Example: Crawling, rolling, tumbling, jumping, running, balancing games

- Combine these movement activities with music

- Musical chairs AKA The Best Game Ever!!

- Encourage children to draw and scribble with markers or pencils (on paper not walls) to develop fine motor skills.

- Allow kids to play

- Experiences with outdoor playground equipment stimulate movement exploration (problem solving) and creative play (critical thinking)

The Science

The importance of movement and sensory experiences was found during studies (find a related article here) that compared brain structures of animals raised in environmentally normal, deprived, and enriched settings. The animals that experienced the enriched settings were given the opportunity to interact with toys, treadmills, and obstacle courses (animal playgrounds). This research led to the conclusion that stimulation is a significant factor in overall brain development. Animals placed in enriched environments had brains that were larger and contained more synaptic connections.

What does this have to do with kids?

"Though animal stand-ins don’t exactly represent the biology of the human brain, their brains have many of the same basic structures and functions," - Dr. Sharon Juliano Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Thus, we can cobble together reasonable theories that can be applied to humans. More information on it can be found here.

(Note: the following is not scientifically verified, but based on our experience over the years with our athletes.) As coaches, we can see the difference in kids who were not active as young children compared to those who were. Kids who were physically active generally have more body awareness, greater overall motor control and strength, and learn new movements relatively easily. At SAPT, let"s say we have an athlete who struggles with the aforementioned skills. We program rolls, crawls, jumps, tumbling drills, and toss-and-catch drills. Guess what? That usually produces vast improvements in their global movement patterns (like the squat or lunge pattern, for example). Not only that, but as their confidence increases as they improve, which only leads to even more improvements as they tackle new exercises and movements. Win!

What that all boils down to is: MOVEMENT! Young kids, (infants, toddlers, etc) need to move. Movement is how they explore and learn about their bodies and how to respond to their environment. Those first 7 years are critical when it comes to developing their motor map. Play on!

Strength Training for Youths: Post-Puberty

Last post delved into training strategies for kids pre-puberty. Today we'll discuss weight training suggestions for kids after they've hit puberty. As I stated before, the American Pediatric Association states that puberty starts around 8-13 (girls) and 10-14 (boys). While a 10 year-old girl might be at the same sexual maturity as a 16 year-old girl, physically, mentally, and emotionally, they're vastly different. Therefore, I'm not going to train a 10 year-old the same as I do a 16 year-old.

So what's different?

To be perfectly honest: not much.The same principles of training youths apply across the age span.

1. Address and improve movement quality

2. Improve body awareness, muscular control, and coordination

3. Progressively overload (add weight or increase the difficulty of exercises) movements to produce positive adaptations appropriate to the athlete's physiological status. (Lotta big words for saying challenge the athlete to grow stronger in ways that will not hurt them.)

Coaches and trainers should always address movement above all. If the athlete moves like poop, adding weight is only going to ingrain the dysfunction that could, ultimately, lead to injury.

That being said, there are a few differences between the two age groups. Older athletes will, typically*, learn movements faster. They've been around longer, played more sports (hopefully), and have a fairly rich movement map. Thus, as they learn proper mechanics quickly, they can handle heavier loads sooner. Does this mean max effort? NO! (stop it, stop that nonsense right now!) It means they can SLOWLY add weights over the course of several months/years to their movements. Strength gains are a marathon, not a sprint.

Older athletes are ususally better at maintaining focus during their workouts (though not always...). This allows room for exercises that require more concentration. For example, an older teenager might front squat with a barbell-

-whereas a younger athlete will squat with a light kettlebell. The barbell squat requires (strength, duh) a greater amount of focus as the athlete has to remain tight to stabilize the bar as well as move in a correct squat pattern. Does this mean a 16 year-old moves straight to the barbell? Nope! They have to prove that a) they have the ability to move in a safe squat pattern (hips back, chest up, knees out) and b) they have the strength (core, upper back, legs). At SAPT we will NOT progress an athlete beyond what we think they're capable of just for the sake of using a barbell.

Older athletes can generally handle more complex movements. For example, a heiden to a med ball throw:

Versus our younger athletes who will work on those two movements independently (jumping and landing, and throwing a ball correctly).

Again, and I can't say this enough, progression should be tailored to the athlete's skill and ability. Throwing a barbell on the back of a teenager just because he's 17 doesn't mean he's able or ready to squat with that barbell. Being 17 does mean that, if he's demonstrated good movement and strength, we can probably progress him to the barbell (we wouldn't do that for a younger kid. They would just continue with kettlebell variations until they've grown a bit more).

The basic principles of training youths across the age-range are the same:

1. Address and improve movement quality

2. Improve body awareness, muscular control, and coordination

3. Progressively overload (add weight or increase the difficulty of exercises) movements to produce positive adaptations appropriate to the athlete's physiological status.

Older athletes will generally be able to:

1. Learn and load movements more quickly than younger athletes

2. Perform exercises that require more concentration

3. Perform more complex exercises

Overall, training youths is like vanilla ice cream: same flavor, different sprinkles.

*I say "typically" because we've seen older kids who have such poor motor control that we have to start them out as we would a 9 year-old and progress them accordingly. What a child does during their infant and toddler years matters! (oooo, teaser for next week!)

Strength Training for Youths: Pre-Puberty

Last week's post listed persuasive (I think so anyway) reasons why kids should enroll in a strength training program. In that post is also a definition of a smart, sound training program. If you can't remember, here's the refresher; it involves none of the max effort, grunting/screaming/shouting version that, unfortunately, is the stereotype of our industry. Parents: NOT ALL TRAINING PROGRAMS ARE CREATED EQUAL!!!

Matter of fact, if you find your 9 year-old doing the same workout as your 16 year-old, something is dreadfully amiss. This post and the next will shed light on the differences that you should see between age groups, broadly, pre-puberty and post-puberty. Now, one thing to keep in mind as you read, these are general guidelines that apply to most of the population. There will be some puberty-stricken kids that are not prepared to train like their peers (meaning, they will be regressed considerably) and there will be some young kiddos who's physical development far exceeds their peers (though it does NOT mean they're ready for large loads; instead they'll have more advanced bodyweight and tempo variations.).

Right, let's hop in.

According to the American Pediatric Association, puberty starts between 8-13 for girls, and 10-14 for boys. For today's discussion, let's assume 15 years is the game changer in physical development. In my experience, kids under 15 still are pretty goofy and often don't have the muscular development that a 15 or 16 year old will (boy or girl). Between 8-15 a LOT of growth happens (and beyond for most boys, but we'll ignore that for now). That segues nicely into my first point:

Strength to weight ratio is a key factor to keep in mind while programming for younger kids. As I mentioned in the prior post, kids grow rapidly and without strength training, their muscle power will be left in the dust. Inadequate muscular strength will force kids to rely on their passive restraints during athletic movement. For example: a baseball pitch (or throw) will require strength in the lower body to produce rotation power, strength in the upper back and rotator cuff to maintain scapular and humeral (shoulder blade and upper arm bone) stability, and a strong core to transfer the power from lower to upper body.

This means, Jonny's shoulder and elbow ligaments are going to take a beating if he's throwing with weak muscles.

Another example: changing direction on a soccer field. The athlete must be strong enough to decelerate herself and then accelerate in a new direction. What happens if her hamstrings, glutes, quads, and core aren't strong enough to stop the motion, stabilize her joints, and reapply force in a new direction? (and this just her body weight, mind you, no external load) Strained (at best) knee ligaments, which typically manifests as the nefarious "knee pain," or, at worst, torn ligaments (good-bye ACL...).

A strength training program for a young athlete that uses heavy weights will only continue to teach the athlete to rely on passive restraints. Why? The athlete is already at a disadvantage by way of rapid growth (the strength:weight ratio is already out-of-whack). Therefore, exercises that utilize body weight or very low weights will avoid overloading the muscles and teach the athlete how to actually use their muscle mass.

The next point is tandem- teaching motor control and body awareness to younger athletes will improve their performance quickly. Kids need to understand MOVEMENTS before they can be expected to load those movements. Focusing on technique is crucial during this growing stage as their adjusting to their new bodies. Teaching kids how to use their hips (instead of their knees or lower back) in a squatting, deadlifting, and rotational pattern will benefit them immensely. Drills that include cross body movements (such as rolls and crawls, meaning left and right side have to coordinate) build "movement" bridges across the two hemispheres of the brain. A coordinated brain means a coordinated body.

Balance drills, such as standing on one foot while performing a medicine ball toss, are excellent in training the vestibular systems (inner ear) as well as teaching the brain to understand the feedback being sent by the foot.

The third point, is key. It must be FUN! Older kids often have the maturity to focus. Younger kids... it's debatable. Some kids are rock stars and can focus better than most adults, however, those athletes are few and far between. Most kids between 8-13 have shorter attention spans and lower stamina than their teenage counterparts. Therefore, we try to make the drills as fun as possible, while still teaching them technique and increasing strength. It's like hiding cauliflower in mac-n-cheese. Hide the good stuff with the delicious stuff. Un-fun sessions lead to unmotivated and easily-distracted athletes... which we all know will not advance their potential at all.

To sum it all up:

1. Focus on increasing strength:weight ratio utilizing body weight/light weight variations to teach young athletes to use their muscles.

2. Incorporate coordination and body awareness drills to TEACH MOVEMENT!

3. Keep the program fun!