Would you have considered this?

I was asked today by the GA at the university I work at why I haven’t backed squatted the baseball or softball teams since they’ve been under my watch. My feelings are as follows: When you do the cost to benefit ratio of the movement (back squat), as any strength coach should do when programming, in my opinion there just isn’t enough benefit to outweigh the potential risk or cost I could potentially incur by selecting it. Understand that properly positioning the hands during a back squat requires a significant amount of shoulder external rotation (especially with close grips), and abduction of the humerus (especially with wide grips). Because either positioning pose a unique risk to the shoulder, the first anterior instability and the latter cranky rotator cuffs and biceps, I’m not about to roll the dice. Also consider that most overhead athletes possess some degree of labral damage, are at a higher risk for impingement, and possess less than stellar scapular upward rotation and thoracic mobility, and you’d have to be feeling pretty sassy to program the back squat. Note that I am working diligently to improve their structural shortcomings because I do intend for them to back squat at some point in their yearly preparation as, in my opinion, the back squat is king when trying to develop strong, powerful badunka-dunks and pork chords.

I think it’s important for those reading this post, whether you’re a young strength coach, or parent shopping around for the best training facility to send you’re little leaguer, to take note that there really is no such thing as an “insignificant detail” when attempting to develop the safest, most effective training program possible.

That's a picture of me hitting the pill a long way...or maybe I swang through it...at least I looked good...

Chris

How Low Should You Squat?

I was hanging out with some good friends of mine over the weekend, and one of them asked me about a hip issue he was experiencing while squatting. Apparently, there was a "clicking/rubbing sensation" in his inner groin while at the bottom of his squat. I asked him to show me when this occurred (i.e. at what point in his squat), and he demoed by showing me that it was when he reached a couple inches below parallel. Now, I did give him some thoughts/suggestions re: the rubbing sensation, but that isn"t the point of this post. However, the entire conversation got me thinking about the whole debate of whether or not one should squat below parallel (for the record, "parallel," in this case means that the top of your thigh at the HIP crease is below parallel) and that"s what I"d like to briefly touch on.

Should you squat below parallel? The answer is: It depends. (Surprising, huh?)

The cliff notes version is that yes in a perfect world everyone would be back squatting "to depth," but the fact of the matter is that not everyone is ready to safely do this yet. I feel that stopping the squat an inch or two shy of depth can be the difference between becoming stronger and becoming injured.

To perform a correct back squat, you need to have a lot of "stuff" working correctly. Just scratching the surface, you need adequate mobility at the glenohumeral joint, thoracic spine, hips, and ankles, along with possessing good glute function and a fair amount of stability throughout the entire trunk. Not to mention spending plenty of time grooving technique and ensuring you appropriately sequence the movement.

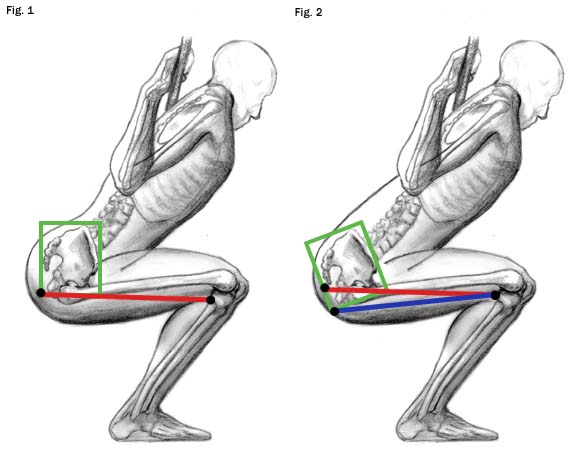

Many times, you"ll see someone make it almost to depth perfectly fine, but when they shove their butt down just two inches further you"ll notice their lumbar spine flex (round out), and/or their hips tuck under, otherwise known as the Hyena Butt which Chris recently discussed.

If you can"t squat quite to depth without something looking like crap, I honestly wouldn"t fret it. Take your squat to exactly parallel, or maybe even slightly above, and you can potentially save yourself a crippling injury down the road. It amazes me how a difference of mere inches can pose a much greater threat to the integrity of one"s hips or lumbar spine. The risk to reward ratio is simply not worth it.

The cool thing is, you can still utilize plenty of single-leg work to train your legs (and muscles neglected from stopping a squat shy of depth) through a full ROM with a much decreased risk of injury. In the meantime, hammer your mobility, technique, and low back strength to eventually get below parallel if this is a goal of yours.

Not to mention, many people can front squat to depth safely because the change in bar placement automatically forces you to engage your entire trunk region and stabilize the body. You also don"t casino online have to worry about glenohumeral ROM which sometimes alone is enough to prevent someone from back squatting free of pain.

Also, please keep in mind that when I suggest you stop your squats shy of depth I"m not referring to performing some sort of max effort knee-break ankle mob and then gloating that you can squat 405. I implore you to avoid looking like this guy and actually calling it a squat:

(Side note: It"s funny as that kind of squat may actually pose a greater threat to the knee joint than a full range squat....there are numerous studies in current research showing that patellofemoral joint reaction force and stress may be INCREASED by stopping your squats at 1/4 or 1/2 of depth)

It should also be noted that my thoughts are primary directed at the athletes and general lifters in the crowd. If you are a powerlifter competing in a graded event, then you obviously need to train to below parallel as this is how you will be judged. It is your sport of choice and thus find it worth it to take the necessary risks of competition.

There"s no denying that the squat is a fundamental movement pattern and will help ANYONE in their goals, whether it is to lose body fat, rehab during physical therapy, become a better athlete, or increase one"s general ninja-like status.

Unfortunately, due to the current nature of our society (sitting for 8 hours a day and a more sedentary life style in general), not many people can safely back squat. At least not initially. If I were to go back in time 500 years I guarantee that I could have any given person back squatting safely in much less time that it takes the average person today.

A good way to improve your deadlift lockout…tear your calluses…and old skool video footage to prove it!!!

Today, from the vault I share with you deadlifting against bands. Staring myself, and two of my old training partners, with musical contributions by the great Earl Simmons aka DMX, the most prominent members of all the Ruff Ryders.

Applications for, and what I like about, pulling against bands:

-Great for improving lockout, or “crushing the walnut” as we say at SAPT. In retrospect, I’d program these in more of a speed, or dynamic, fashion as opposed to max effort (as seen in the video). I feel training the speed in which the hip extension occurs will ultimately have a greater carryover.

-You can really overload lockout without having to perform the movement in a shortened ROM (i.e. rack pull). Additionally, the overload at the top absolutely slams your grip, and promotes the adaptations necessary to handle your 9th max effort attempt of the day (in the case of a powerlifting competition which we were training for at the time).

-They are a great way to rip the calluses right-off your hand! You’ll notice at the 1:12 mark I do a dainty little skip at the end of my set; ya, that’s where I partially tear the callus, and then at the 1:45 mark is where I finish it off. Great, thanks for sharing, Chris.

***Note, a great way to keep your calluses at bay is while in the shower gently shave over them with your standard razor. This removes most of the dead skin while not removing the callus all together. Thanks, Todd Hamer!***

What I don’t like about pulling against bands:

-Kind-of a pain to set-up.

-They put the bar in a fixed plane which may be detrimental for some trying to find their groove.

-From a programming standpoint I feel that they are more of an advanced progression and therefore aren't appliciable to most.

-They’ll rip the calluses right-off your hand!

Yes, it should be noted that the lifting form exhibited in the video, by one individual in particular (crappy, fragmented footage used to protect the innocent), should not be used as reference for a “how to” deadlift manual. Might I suggest you focus on the swarthy young-man in the green t-shirt…

Good times…hard to believe it’s been three years…

Chris AKA Romo

Teaching Triple Extension

Want to work on improving everything from linear sprint speed, power, change of direction, force production, vertical jump, and deceleration strength? I know, who doesn’t, right? These qualities should be included in the very definition of athletic success.

The triple extension is a huge key aspect to unlocking all of these qualities in concert. It is also the component that is common through virtually all the movements that come to mind when thinking about the ideal strong, fast, and powerful athlete. Some good examples are a wrestler shooting, a sprinter coming off the blocks, throwers at the point of release, the vertical jump in a volleyball attack, etc.

What is Triple Extension?

Triple extension is the simultaneous extension of three joints: ankle, knee, and hip. Getting all of these areas to extend powerfully at the perfect moment is a beautiful and natural occurrence. Mess it up and, well, it looks really bad…

Why should Triple Extension be taught, developed, and progressed?

Again, if you’re looking to unlock and develop the athletic potential in yourself or an athlete under your guidance, then triple extension work is a must. Perfection of this movement during training will result in a faster, more powerful athlete on the court, field, or mat. And if you’re faster and more powerful, you WILL be more successful and less injury prone.

Teaching Progressions:

- Basic Bodyweight Strength Exercises – pushups, pull-ups, body weight squats, body weight lunges, etc. should all be considered foundational portions of any athletic development program and should NEVER be skipped. Trust me, no one is “too advanced” for this type of work. These movements have their place in any program whether they appear in the warm-up or the body of the training session.

- Medicine Ball Overhead Throw – this particular exercise allows triple extension to occur. However, I like using other MB variations to teach a powerful hip extension like a Scoop Throw. I suggest 2-3 sets of 4-6 repetitions for beginners and 3 sets of 2-5 repetitions for more advanced athletes.

- Broad Jump and Vertical Jump Variations – these are fantastic because you can add subtle variations almost endlessly to increase or decrease intensity/difficulty for every athlete’s needs. Plus, this is a great opportunity to teach takeoff and landing technique to avoid the dreaded and dangerous knee collapse. Common variations I use regularly include: broad jump, burpee to broad jump, single leg broad jump, vertical jump, hot ground to vertical jump, vertical jump to single leg landing, etc, etc, etc… Sets and reps are the same as med balls at 2-3 sets of 4-6 repetitions for beginners and 3 sets of 2-5 repetitions for more advanced athletes.

- Sprint Variations – Numbers 1-3 are progressed over the course of at least 12-weeks for beginners (less for more advanced athletes), sprinting variations can be added to encourage exceptional high quality triple extension repetitions. Generally for this application of sprints the distance should be kept quite short. I find 5-20 yards hits the right spot. At this point we should be dealing with an athlete that can, minimally, be considered “intermediate” in level and with that qualification I suggest 6-20 sets of 1-3 repetitions at a distance of 5-20 yards. The higher the number of sets, the shorter the distance and the lower the number of reps should be. Oh, and be sure to allow for full recovery for achieving power and speed development.

- Speed Squats – Hands down my favorite style of lower body exercise. This movement type teaches athletes how to produce force by pushing hard into the ground and accelerating up as fast as possible. These variations include the traditional Speed Squat, Wave Squat, and Jump Squat. Speed squat variations should ONLY be used with ADVANCED athletes. I suggest 6-10 sets of 2-3 reps with about 45-seconds rest between sets. Weight should be kept at 55-65% of the athlete’s 1RM squat.

- Olympic Lifting Variations – Please take note that this is the absolute last suggestion of my list of progressions for teaching the Triple Extension, but it is the variation that inexperienced (and in my opinion misguided) coaches frequently jump to first. Olympic lift variations have their place with highly advanced and elite level athletes. However, I rarely use them. Why? Because through my experience I have found that one can elicit faster and greater gains via cycling through numbers 1-5. However, I do use them sparingly with some athletes. I have to admit the athleticism required for Oly lifts can make executing them a lot of fun, but there is a requirement of athleticism!! It makes me sick to my stomach how many coaches are on some kind of auto-inclusion of each and every Olympic variation for each and every athlete. What a mistake! Including these in a program too soon leads to poor form and execution which means you’re not getting that much bang-for your-buck with the movements (i.e., wasting time) and would be better off regressing to something more straightforward. Anyway, some great variations include the jump shrug, high pull, hang clean, etc. Keep the sets moderate and reps LOW.

You really can’t make a mistake if you cool your jets and follow this progression slowly. Remember, untrained athletes will get stronger and faster with very little stimulus. So take your time and learn to enjoy and respect the process!

7 Days of Insanity

Over the past 7 days I’ve had multiple experiences every day that I think most Strength & Conditioning Coaches would kill to experience with NCAA Division 1 athletes. Last week was one of those special weeks when I’ve got a couple of my teams in-season, a couple teams in pre-season, and several teams just getting started for the semester with testing. The last week was extremely rich with everything from recovery sessions for soccer, 1RM squat testing, conditioning for two teams, and working out the details of a new research project. I even saw an ACL completely tear and another one we thought tore, but – thankfully – did not. My point in this post is to give you a weeklong peek into the life of a college strength coach… and let me tell you, it is WAY different than the private sector.

Tuesday, September 6:

- 8:30a – women’s soccer in weight room for a light total body lift, capped on either end of the session with active & static stretching and SMR (foam rolling).

- 10:30a – women’s basketball in weight room for an upper body lift. We then go over to the Patriot Center to begin conditioning by 11:15a. Post players ran routes on the court and guards ran stairs.

- 2:00p – on the field with women’s soccer to run their warm-up and conditioning routes.

- 3:30p – female sprinters and jumpers in weight room for power clean 1RM testing.

- 3:45p – throwers testing 3 vertical jump variations: counter-movement, static start, depth jump (from low box).

- 4:30p – male sprinters and jumpers in weight room for power clean 1RM testing.

Wednesday, September 7:

- 8:45a – women’s volleyball in weight room to lift. The start and finish of the lift involved active & static stretching and SMR.

- 2:00p – on the field to warm-up women’s soccer.

- 2:30p – women’s lacrosse testing on single leg broad jump, vertical jump, and 3RM front squat to BELOW parallel depth (we had a freshmen hit 170 x 3 – yikes!)

- 3:30p – female sprinters and jumpers in weight room to test 1RM bench press.

- 4:30p – male sprinters and jumpers in weight room to test 1RM bench press (one guy pressed 305lbs)

Thursday, September 8:

- 10:30a – women’s basketball in weight room for a lower body lift. We then go over to the Patriot Center to begin conditioning by 11:15a. Guards ran routes on the court and posts ran a low impact total body conditioning circuit.

- 2:00p – lead an on-field body weight only training session for women’s soccer (technically it wasn’t “on-field” due to the monsoon outside… we were in the Field House).

- 3:00p – rowing team in weight room for first day of training – big team with 15 new athletes means lots of instruction.

- 3:30p – female sprinters and jumpers in weight room to test ½ Squat 1RM

- 3:45p – throwers in weight room to test bench press 1RM and review lifts for following week.

- 4:30p – male sprinters and jumpers in weight room to test ½ Squat 1RM.

Friday, September 9:

- 10:30a - women’s basketball in weight room for an upper body lift. We then go over to the Patriot Center to begin conditioning by 11:15a. Post players ran routes on the court and guards ran stair sprints with full recovery.

- 2:30p – women’s lacrosse testing for seated MB Toss, Perfect Pushup Assessment for 1 set of 10, Yo-Yo Intermittent Beep test.

- 3:45p – throwers in weight room for 1RM back squat test with introduction of following week’s lower body lifts.

Saturday, September 10:

- 10:00a – on-field with women’s soccer for practice.

Sunday, September 11:

- 1:00p – women’s soccer game. Witnessed a member of the opposing team destroy her ACL during a contact situation. I’ve seen this before and I’ll see it again, many times I’m sure. It’s always terrible to see this type of season ending injury that, because of my background and experience, I know will affect her for the rest of her life.

Monday, September 12:

- 8:45a – women’s volleyball in the weight room for lifting. The start and finish of the lift involved active & static stretching and SMR.

- 10:30a - women’s basketball in weight room for a lower body lift. We then go over to the Patriot Center to begin conditioning by 11:15a. Guards ran routes on the court and Posts ran stairs for speed work with full recovery.

- 1:30p – Single lacrosse player in to lift.

- 2:30p – women’s lacrosse in for first lifting session. Lots of teaching.

- 3:45p – throwers in for first lifting session. We did some serious volume with some serious low rest periods. No one threw-up, amazing! They must have been ready for it!

- 4:30p – female sprinters and jumpers in for first lifting session.

- 5:30p – male sprinters in for first lifting session.

Congratulations, you made it to the end of my 7 days!!! I don’t have the time or the patience to convey the details that were left out of this recap, but trust me when I tell you I think I garnered an additional year’s worth of experience in just 7 days.

As I’ve seen many very talented strength coaches completely leave the field over my 7-years of experience, I have learned that being a college strength coach is not everyone’s cup of tea. But for some sick reason it seems to be mine. I thrive on the stress and intensity. If you’re thinking of stepping into the college environment, reread my week above one more time and factor in having a life (and in my case a business, too) on top of all that – can you handle it?

Fall Your Way to Faster Sprint Times: The Falling Start

Who doesn't want to sprint faster? Whether you're a competitive athlete, a weekend warrior, or simply someone who wants to win the next random "tough guy" challenge at a BBQ, the ability to sprint quickly certainly can't be a negative addition to your toolbox.

It's tough to find a better means of true plyometric training than sprinting, and, on top of that, there are few human movements that simply feel more "freeing" than sprinting. There's no denying that it's just plain fun.

However, most of us find ourselves in a devilish conundrum here: Sprinting faster - and safely - isn't just about going out and sprinting. Why, you ask?

- Most people simply lack the strength to efficiently decelerate (and subsequently accelerate) during each stride. The remedy to this lies in ensuring your involvement in a sound strength training regimen. I discussed the "why" behind the importance of strength for increased speed in the Improving My Son's 60-Yard Dash Q & A I wrote last year (see the third point), so I'm not going to bore you here.

- The majority of us move like crap. As such, heading out to the track for 100yd repeats for our first "sprint" session is a recipe for pulled adductors, hamstrings, and hip flexors (admittedly, this happened to me in college so I'm allowed to make fun of those that currently do it). Given that most people sit the majority of the day, possess glaring flexibility deficits, and haven't sprinted in a while, going balls-to-the-wall right off the bat is about as intelligent as thinking you can win a cage match against Wolverine.**

This being said, I prefer to ease people into sprinting, utilizing short bouts of 80% intensity to begin with. These will typically be completed at 20-yards OR LESS. This way, the person won't be able to reach full acceleration and reduce the risk of incurring an "ouchie." Not to mention, nearly everyone's sprint times can be lower by working on the first ten yards alone, due to the fact that the start of the sprint is where you lose most of your time.

Here's a drill I like to use to ease into sprinting, on top of helping teach someone how to produce large amounts of force into the ground:

Falling Start

Some of the key points:

- Fall. Seriously, fall forward as far as possible. You want to lean so far that you would literally fall on your face if your feet don't catch up to you. This is critical to creating the momentum we're looking for in acceleration, as well as nearly (but not completely) approximating the body angle required for acceleration one would experience out of the blocks. This is where Matthew (the one demonstrating) is better at this drill than the majority of people I've seen do it, as most tend to think they've leaned further forward than they actually have.

- As you lean forward onto the balls of your feet, be sure to keep the hips forward (i.e. body should be stiff as board, like you're a falling plank...no bending at the waist).

- As you drive out of the fall, maintain that forward lean and be vigorous with your arm action. Drive those elbows "front to back" and keep the palms open/relaxed (again, Matthew does a pretty good job with this).

- Try your best to keep the chin tucked throughout the acceleration, too. The only main critique I have for Matthew's demo is that he looked up - hyperextending his neck - as he drove out of the start.

- Keep your sprint distance to 10-20 yards, especially in the early stages of training. In the video, Matthew only accelerates through the eight yard mark before slowing down.

There you have it. While there are countless drills you can use to "improve that first step," I really like this one for people just starting out with their sprint work, as well as mixing in the programs of those toward the "advanced" side of the spectrum, too.

**unless your name is Magneto.