Would you have considered this?

I was asked today by the GA at the university I work at why I haven’t backed squatted the baseball or softball teams since they’ve been under my watch. My feelings are as follows: When you do the cost to benefit ratio of the movement (back squat), as any strength coach should do when programming, in my opinion there just isn’t enough benefit to outweigh the potential risk or cost I could potentially incur by selecting it. Understand that properly positioning the hands during a back squat requires a significant amount of shoulder external rotation (especially with close grips), and abduction of the humerus (especially with wide grips). Because either positioning pose a unique risk to the shoulder, the first anterior instability and the latter cranky rotator cuffs and biceps, I’m not about to roll the dice. Also consider that most overhead athletes possess some degree of labral damage, are at a higher risk for impingement, and possess less than stellar scapular upward rotation and thoracic mobility, and you’d have to be feeling pretty sassy to program the back squat. Note that I am working diligently to improve their structural shortcomings because I do intend for them to back squat at some point in their yearly preparation as, in my opinion, the back squat is king when trying to develop strong, powerful badunka-dunks and pork chords.

I think it’s important for those reading this post, whether you’re a young strength coach, or parent shopping around for the best training facility to send you’re little leaguer, to take note that there really is no such thing as an “insignificant detail” when attempting to develop the safest, most effective training program possible.

That's a picture of me hitting the pill a long way...or maybe I swang through it...at least I looked good...

Chris

Intensity: Get Some.

This post is written by the legendary Steve Reed You know what's interesting? Let's pretend I'm writing a program for two people that are nearly identical in EVERY WAY. They are of the same gender, carry the same body fat %, have the exact same metabolic rate, same poundage of lean body mass, are of the same biological and chronological age, are equivalent in neural efficiency, possess the same number of high threshold motor units, etc., you get the idea.

The program I write for both of them could be a perfect blueprint for fat loss, mass building, athletic performance enhancement, you name it. Yet, one of them will walk away, sixteen weeks later, looking and moving like a completely different person, while the other will move and look the exact same as they did when they started.

How could this be?

Well, I said that the two people are nearly equivalent. They are the same in every way, except for one key element. This critical difference is in their mindset. Namely, the former follows the plan with INTENSITY. Focus. Passion. Conviction.

The latter, however, follows the plan with the enthusiasm of a gravedigger. There's no light in their eyes as they move the weights around, and it's as if they're performing a chore for their parents before they get to what they really want to do. As Tony Gentilcore put it, their approach to squatting and deadlifting resembles a butterfly kissing a rainbow.

I was thinking about this the other day as I was observing the eclectic training mentalities I see on a weekly basis at my local commercial gym, and even sometimes at SAPT with people who walk through our doors for the first time. Especially when it comes to the accessory work (i.e. the movements after the squat/bench/deadlift portion of the session), you tend to really see a drop-off in focus.

Sometimes, when I show something like a band pullthrough, glute bridge, or face pull, it's obvious the person doesn't care too much, and/or is worried what others may think:

"Man, this looks awkward" "This movement can't really be of any importance" "I wish he'd stop giving me this stupid exercise"

Let's take the band pullthrough and the face pull. This is what it may resemble:

If you go through the motions like this, how do you expect anything to happen?

Now, take Carson, one of our student-athletes. This kid gets down to business on everything. And I mean EVERYTHING. Bulldog hip mobility drills, walking knee hugs, broad jumps, band pullaparts, assistance work, and God help you if you get in his way while he's deadlifting.

I saw him training the other day and knew I had to film a few of his exercises. See the video below, and keep in mind he is not acting. This is how he actually lifts:

I mean, look at that face!!! He's thinking about NOTHING ELSE outside the immediate task at hand. He's snapping his hips HARD on those pullthroughs, and even during the sledge leveraging he's eying that hammer like he wants to kill it.

And, is it a surprise that Carson hit a 55lb deadlift personal record in a mere 12-week cycle with us?

Of course not. I wouldn't expect anything less with mindset like his.

It's time to train with some freakin' conviction and purpose when you enter the weight room. In fact, I'd even say become BARBARIC as you approach the iron. Even with your assistance work, take it on like you mean it. Then watch the results pour in.

Look, I do understand that many times there are external circumstances that may tempt to affect your mentality, both in and out of the weight room. And that not all of you feel very comfortable in the weight room, as it may be a fairly alien environment to you. Even if you're new to the gym and initially feel comfortable with just a few goblet squats and then getting on the treadmill, still attack it like you mean it! The faster you learn to "leave it all at the front door," the better off you'll be, and that's a promise.

The weight room has helped me through some of the most difficult times of my life. Sometimes it seems that iron seems like the only thing in the world that remains consistent to us. Two hundred pounds sitting there on the barbell is always going to be two hundred pounds.

So get in there and train like you mean it. Don't make me light some fire under those haunches!

Long-Term Development of Athletes

Let’s suppose you are putting together a team composed of 18-22 year old athletes – any sport will do, pick your favorite – you have already filled out the roster with the exception of one remaining spot. Thus far you have a balanced player profile: everyone has better than average levels of physical and psychological attributes. For that last open spot you’ve got the decision down between two players – Athlete A is clearly a physical specimen (i.e., they look dominant and are extremely fast/powerful), but has very little formal training in the sport or organized physical preparation. Athlete A can best be described as a good project, a blank canvas, or a risky bet with potentially a huge upside. This player will need much formalized physical training and sport specific technical instruction/drilling to become a team asset.

Athlete B will fit in well physically with the team and this athlete has excellent decision making abilities. You know this athlete has been involved in a long-term development program that has covered both sport specific and physical preparation. This player will provide consistent practice and game efforts and be solid foundation for the rest of the team by being an example of superior work ethic, positive attitude, and maturity from which the rest of the team can learn. However, Athlete B does not have the “star power” of A.

Which one do you choose to round out your team?

Before I come out with MY answer, I’ll give you more detailed background information on the long-term development model and answer the following questions:

How does the long-term model look? When does it begin and why?

To achieve what is TRULY high performance, six to eight years of preparation is required (here I am referring to both general physical and sport specific preparation). So, this process will actually start as early as age 10. And, believe it or not (well, you should believe it), the DETAILS of the planning day-by-day, week-by-week, and year-by-year make THE difference in seeing an individual achieve their true potential or falling a little short by the time they are 18 years of age.

Training can be divided into four main sections during the six to eight years of preparation:

| Training Classification | Age Range | Goals |

| Basic Training (3 yrs)

|

Ages 10-12 | A general, non-specific approach with all-round balance. Variety is the key as children are developing multiple motor coordinative abilities along with strength, speed, and mobility. Technique MUST be precisely learned and part of the program must include developing sprint mechanics. |

| Build-Up Training (3 yrs) | Ages 13-15 | Aims to develop a large catalogue of techniques and general motor-coordination skills. Other goals include development of endurance, speed, reactive ability, all-round strength, mobility/flexibility, and a high standard of performance in a mult-event test (Heptathlon). |

| Connecting Training (3 yrs) | Ages 16-18 | At this point the athlete has decided about his/her specialty (the sport). The main goal at this point is to extract sport specific performance abilities utilizing NON-SPECIFIC training means and increasing the proportion of maximum strength training methods. |

| High Performance Training (2-3 Olympic Cycles) | Age 19 and older | Having developed to this point, the athlete is now prepared for high level performance training that can involve numerous means, methods, and theories to extract the needed performance. |

Hopefully, you can see from this table how involved the athlete development process should be. Europe has had an amazing talent development process in place for decades, unfortunately the same cannot be said for the United States. I regularly encounter parents, athletes, and coaches with little respect for the power, importance, and impact that an appropriately developed strength training and conditioning program can have on a developing athlete (and, more importantly, a quality person). Why is there a difference? Well, it is simply a by-product of how physical education programs are run in schools and how the club sports model has developed.

But, back to my question: between Athlete A and Athlete B, which one would you choose to fill out your roster?

In this scenario, I would choose Athlete B every single time. Athlete B has a solid skill set with a great deal of experience in formal training to complement that experience. Additionally, by understanding their long-term physical preparation approach, I would also feel comfortable in knowing that there is little chance this athlete would incur overuse or non-contact injuries at a higher level of competition.

In my opinion Athlete A is too far behind in the development process to see a big upside with only a few short years of development. A’s motor patterns are already completely set and it is unlikely A could make the changes in faulty motor patterns that are essential for technical execution in sport. In addition, there is a high likelihood that their mental toughness and attitude will not be up to the rigors of all the challenges to be encountered in a fast-tracked development program. It could be like trying to stuff 10 pounds of sand into a 5 pound bag… it just ain’t gonna happen.

Before I wrap up, I do want to note that if your child does not start this process at age 10 or even by age 12, all is not lost! You can fast track the process just a bit. The real key is to try to get children into this type of formalized training before all of their motor patterns are established and “set in stone” – this happens around age 15 or 16. In this case, the “ideal” model above will be adjusted to the following:

| Training Classification | Age Range | Goals |

| Basic Training & Build-Up Training Combined (2 yrs)

|

Ages 16 and 17 | Although the athlete may already be specialized in their sport, time must still be spent on very general physical preparedness and learning exact technique. |

| Connecting Training (2 yrs) | Ages 18 and 19 | The main goal at this point is to extract sport specific performance abilities utilizing NON-SPECIFIC training means and increasing the proportion of maximum strength training methods. |

| High Performance Training (2-3 Olympic Cycles) | Age 20 and older | Having developed to this point, the athlete is now prepared for high level performance training that can involve numerous means, methods, and theories to extract the needed performance. |

We regularly begin formal general physical preparation for our athletes around age 14-16 and see phenomenal performance results over time. But, if you have the means or your own knowledge base, you should strive to get your kids started between ages 10-12.

In the end, the physical performance is rewarding, but short-term. The personal development and increased confidence a young person gains from this process is the real benefit that will last a lifetime.

How Low Should You Squat?

I was hanging out with some good friends of mine over the weekend, and one of them asked me about a hip issue he was experiencing while squatting. Apparently, there was a "clicking/rubbing sensation" in his inner groin while at the bottom of his squat. I asked him to show me when this occurred (i.e. at what point in his squat), and he demoed by showing me that it was when he reached a couple inches below parallel. Now, I did give him some thoughts/suggestions re: the rubbing sensation, but that isn"t the point of this post. However, the entire conversation got me thinking about the whole debate of whether or not one should squat below parallel (for the record, "parallel," in this case means that the top of your thigh at the HIP crease is below parallel) and that"s what I"d like to briefly touch on.

Should you squat below parallel? The answer is: It depends. (Surprising, huh?)

The cliff notes version is that yes in a perfect world everyone would be back squatting "to depth," but the fact of the matter is that not everyone is ready to safely do this yet. I feel that stopping the squat an inch or two shy of depth can be the difference between becoming stronger and becoming injured.

To perform a correct back squat, you need to have a lot of "stuff" working correctly. Just scratching the surface, you need adequate mobility at the glenohumeral joint, thoracic spine, hips, and ankles, along with possessing good glute function and a fair amount of stability throughout the entire trunk. Not to mention spending plenty of time grooving technique and ensuring you appropriately sequence the movement.

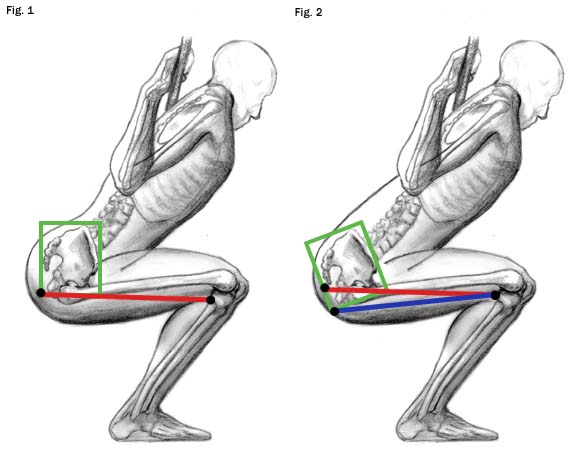

Many times, you"ll see someone make it almost to depth perfectly fine, but when they shove their butt down just two inches further you"ll notice their lumbar spine flex (round out), and/or their hips tuck under, otherwise known as the Hyena Butt which Chris recently discussed.

If you can"t squat quite to depth without something looking like crap, I honestly wouldn"t fret it. Take your squat to exactly parallel, or maybe even slightly above, and you can potentially save yourself a crippling injury down the road. It amazes me how a difference of mere inches can pose a much greater threat to the integrity of one"s hips or lumbar spine. The risk to reward ratio is simply not worth it.

The cool thing is, you can still utilize plenty of single-leg work to train your legs (and muscles neglected from stopping a squat shy of depth) through a full ROM with a much decreased risk of injury. In the meantime, hammer your mobility, technique, and low back strength to eventually get below parallel if this is a goal of yours.

Not to mention, many people can front squat to depth safely because the change in bar placement automatically forces you to engage your entire trunk region and stabilize the body. You also don"t casino online have to worry about glenohumeral ROM which sometimes alone is enough to prevent someone from back squatting free of pain.

Also, please keep in mind that when I suggest you stop your squats shy of depth I"m not referring to performing some sort of max effort knee-break ankle mob and then gloating that you can squat 405. I implore you to avoid looking like this guy and actually calling it a squat:

(Side note: It"s funny as that kind of squat may actually pose a greater threat to the knee joint than a full range squat....there are numerous studies in current research showing that patellofemoral joint reaction force and stress may be INCREASED by stopping your squats at 1/4 or 1/2 of depth)

It should also be noted that my thoughts are primary directed at the athletes and general lifters in the crowd. If you are a powerlifter competing in a graded event, then you obviously need to train to below parallel as this is how you will be judged. It is your sport of choice and thus find it worth it to take the necessary risks of competition.

There"s no denying that the squat is a fundamental movement pattern and will help ANYONE in their goals, whether it is to lose body fat, rehab during physical therapy, become a better athlete, or increase one"s general ninja-like status.

Unfortunately, due to the current nature of our society (sitting for 8 hours a day and a more sedentary life style in general), not many people can safely back squat. At least not initially. If I were to go back in time 500 years I guarantee that I could have any given person back squatting safely in much less time that it takes the average person today.

Breaking Down the Split Squat ISO Hold

The split squat ISO hold is extremely versatile, no matter if we're dealing with a new trainee, an advanced athlete, or someone looking to spice up their routine. It's the traditional split squat, but performed with an isometric (ISO) hold in the bottom of the movement. See the video below:

Why do I like it?

1. It's great for in-season athletes, or during a period leading up to competition. As a strength coach, it's critical to be able to provide the in-season athlete with a training effect, while simultaneously reducing the risk of muscle soreness. What athlete can optimally perform while he/she can hardly move his or her legs because they feel like jell-o?

The split squat ISO hold reduces the risk of soreness because it minimizes the eccentric portion of the lift, where the most muscle damage takes place (and thus contributes to that delayed-onset muscle soreness you typically feel 24-48 hours after a workout).

So, you can still receive a training effect (become stronger and improve neuromuscular control) while simultaneously reducing the soreness commonly felt after a lift. Sounds like a no brainer to me!

2. It's a great teaching tool for beginners. Many people nearly topple over (and sometimes actually do) when first learning the split squat. This shouldn't come as a surprise, as it's always going to require sound motor control when you move the base of support from two feet (as in the traditional squat) to one foot.

For the average person entering SAPT, I'll use the split squat isometric hold to help them learn the position. Depending on the person, I may have them start on the ground (in the bottom position), and then just elevate a couple inches off the ground and hold. This way, they're not constantly having to move through the full range of motion, where the most strength and neural control is required.

3. Like most single-leg variations, it trains the body to work as one flawless unit. As noted in the Resistance Training for Runners series I wrote earlier this year, lunge variations teach the body to work as a unit, as opposed to segmented parts. Specifically: the trunk stabilizers, glutes, hamstrings, quads, TFL (tensor fascia latae), adductors, and QL (quadratus lomborum) will all have to work synergistically to efficiently execute the movement.

4. To use as a change of pace. Yup...

Key Coaching Cues

- Get in a wide stance with the feet parallel to each other (as you'll see when I face the camera).

- Lower straight down. What we're looking for here a vertical shin angle (shin perpendicular to the floor). It's very easy to let the knee drift forward if you're not paying attention.

- Keep a rigid torso (upright). Imagine as if you're struttin' your stuff at the beach.

- Don't let the front knee drift inward (valgus stress). Keep the knee right in line with the middle-to-outside toes. I even cue "knee out" sometimes as many people really let the knee collapse inward.

- Squeeze the front glute to help keep you stable. You can also squeeze the back glute to receive a nice stretch in the hip flexor of the back leg.

- Perform for 1-3 reps (per side) with a :5-:15 hold in the bottom.

A good way to improve your deadlift lockout…tear your calluses…and old skool video footage to prove it!!!

Today, from the vault I share with you deadlifting against bands. Staring myself, and two of my old training partners, with musical contributions by the great Earl Simmons aka DMX, the most prominent members of all the Ruff Ryders.

Applications for, and what I like about, pulling against bands:

-Great for improving lockout, or “crushing the walnut” as we say at SAPT. In retrospect, I’d program these in more of a speed, or dynamic, fashion as opposed to max effort (as seen in the video). I feel training the speed in which the hip extension occurs will ultimately have a greater carryover.

-You can really overload lockout without having to perform the movement in a shortened ROM (i.e. rack pull). Additionally, the overload at the top absolutely slams your grip, and promotes the adaptations necessary to handle your 9th max effort attempt of the day (in the case of a powerlifting competition which we were training for at the time).

-They are a great way to rip the calluses right-off your hand! You’ll notice at the 1:12 mark I do a dainty little skip at the end of my set; ya, that’s where I partially tear the callus, and then at the 1:45 mark is where I finish it off. Great, thanks for sharing, Chris.

***Note, a great way to keep your calluses at bay is while in the shower gently shave over them with your standard razor. This removes most of the dead skin while not removing the callus all together. Thanks, Todd Hamer!***

What I don’t like about pulling against bands:

-Kind-of a pain to set-up.

-They put the bar in a fixed plane which may be detrimental for some trying to find their groove.

-From a programming standpoint I feel that they are more of an advanced progression and therefore aren't appliciable to most.

-They’ll rip the calluses right-off your hand!

Yes, it should be noted that the lifting form exhibited in the video, by one individual in particular (crappy, fragmented footage used to protect the innocent), should not be used as reference for a “how to” deadlift manual. Might I suggest you focus on the swarthy young-man in the green t-shirt…

Good times…hard to believe it’s been three years…

Chris AKA Romo