Why Train In-Season?: Strength and Power Gains

Hopefully by now, you've read about the signs and reversal of overtraining. Now let's look at why and how to train intelligently in-season. A well-designed in-season program should a) prevent overtraining and b) improve strength and power (for younger/inexperienced athletes) or maintain strength and power (older/more experienced lifters).

First off, why even bother training during the season?

1. Athletes will be stronger at the end of the season (arguably the most important part) than they were at the beginning (and stronger than their non-training competition).

2. Off-season training gains will be much easier to acquire. The first 4 weeks or so of off-season training won't be "playing catch-up" from all the strength lost during a long season bereft of iron.

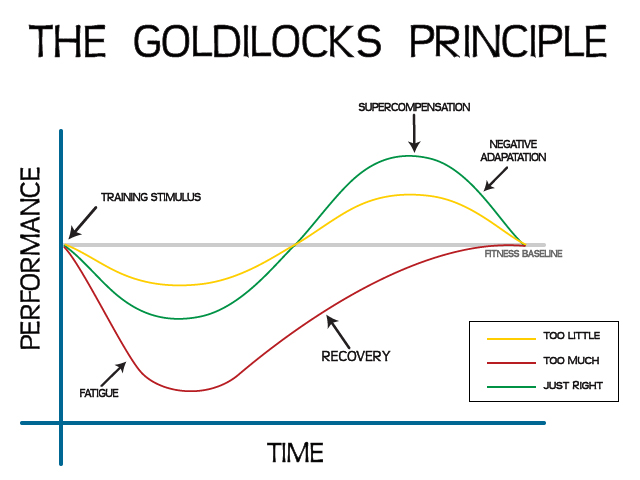

I know that most high school (at least in the uber-competitive Northern VA region) teams require in-season training for their athletes. Excellent! However, many coaches miss the mark with the goal of the in-season training program. (Remember that whole "over training" thing?) Coaches need to keep in mind the stress of practice, games, and conditioning sessions when designing their team's training in the weight room. 2x/week with 40-60 minute lifts should be about right for most sports. Coaches have to hit the "sweet spot" of just enough intensity to illicit strength gains, but not TOO much that it inhibits recovery and negatively affects performance.

The weight training portion of the in-season program should not take away from the technical practices and sport specific. Here are a couple of things to keep in mind about the program, it should:

1. Lower volume, higher intensity-- this looks like working up to 1-2 top sets of the big lifts (squat or deadlift or Olympic lift), while maintaining 3-4 sets of accessory work. The rep range for the big lifts should be between 3-5 reps, varied throughout the season. The total reps for accessory work will vary depending on the exercise, but staying within 18-25 total reps (for harder work) is a stellar range. Burn outs aren't necessary.

2. Focused on compound lifts and total body workouts-- Compound lifts offer more bang-for-your buck with limited time in the weight room. Total body workouts ensure that the big muscles are hit frequently enough to create an adaptive response, but spread out the stress enough to allow for recovery. Note: the volume for the compound lifts must be low seeing as they are the most neurally intensive. If an athlete can't recover neurally, that can lead to decreased performance at best, injuries at worst.

3. Minimize soreness/injury-- Negatives are cool, but they also cause a lot of soreness. If the players are expected to improve on the technical side of their sport (aka, in practice) being too sore to perform well defeats the purpose doesn't it? Another aspect is changing exercises or progressing too quickly throughout the program. The athletes should have time to learn and improve on exercises before changing them just for the sake of changing them. Usually new exercises leave behind the present of soreness too, so allowing for adaptation minimizes that.

4. Realizing the different demands and stresses based on position -- For example, quarterbacks and linemen have very different stresses/demands. Catchers and pitches, midfields and goalies, sprinters and throwers; each sport has specific metabolic and strength demands and within each sport, the various positions have their unique needs too. A coach must take into account both sides for each of their positional players.

5. Must be adaptable --- This is more for the experienced and older athletes who's strength "tank" is more full than the younger kids. The program must be adaptable for the days when the athlete(s) is just beat down and needs to recover. Taking down the weight or omitting an exercise or two is a good way to allow for recovery without missing a training session.

A lot to think about huh? As a coach, I encourage you to ask yourself if you're keeping these in mind as you take your players through their training. Athletes: I encourage you to examine what your coach is doing; does it seem safe, logical, and beneficial based on the criteria listed above? If not, talk to your coach about your concerns or (shameless plug here, sorry), come see us.

Overtraining Part 1: Symptoms

This month's theme is in-season training since the spring sports are starting up. All the practices, games, and tournaments start to add up to over time, not to mention any weight room sessions the coachs' require of their athletes. Lack of proper awareness and management of physical stressors can lead, very quickly in some cases, to overtraining... which leads to poor performance, lost games, increase risk of injury, and a rather unpleasant season.

The subject of overtraining is a vast one and we won't be able to cover all the aspects that contribute, but by the end of this two part series, you should have a decent grasp on what overtraining is and how to avoid it. Today's post will be about recognizing the symptoms of overtraining while next post will offer techniques and training advice to avoid the dreaded state of overtrained-ness. (Yes, I made that word up.) Li'l food for thought: quite often the strength and conditioning aspect of in-season training is the cornerstone of maintaing the health of the athlete. Too much, and the athlete breaks, but administered intelligently, a strength program can restore an athlete's body and enhance overall performance. Right, let's dive in!

Who doesn’t like a good work out? Who doesn’t like to train hard, pwn some weight (or mileage if you’re a distance person), and accomplish the physical goals you’ve set for yourself? Every work out leave you gasping, dead-tired, and wiped out, otherwise it doesn't count, right? (read the truth to that fallacy here)

We all want a to feel like you've conquered something, I know I do!

However, sadly, there can be too much of a good thing. We may be superheroes in our minds, but sometimes our bodies see it differently. Outside of the genetic freaks out there who can hit their training hard day after day (I’m a bit envious…), most of us will reach a point where we enter the realm of overtraining. I should note, that for many competitive athletes (college, elite, and professional levels) there is a constant state of overtraining, but it’s closely monitored. But, this post is designed for the rest of us.

Now, everyone is different and not everyone will experience every symptom or perhaps experience it in varying degrees depending on training age, other life factors, and type of training. These are merely general symptoms that both athletes and coaches should keep a sharp eye out for.

Symptoms:

1. Repeated failure to complete/recover in a normal workout- I’m not talking about a failed rep attempt or performing an exercise to failure. This is a routine training session that you’re dragging through and you either can’t finish it or your recovery time between sets is way longer than usual. For distance trainees, this may manifest as slower pace, your normal milage seems way harder than usual, or your heart rate is higher than usual during your workout. Coaches: are you players dragging, taking longer breaks, or just looking sluggish? Especially if this is unusual behavior, they're not being lazy; it might be they've reached stress levels that exceed their abilities to recover.

2. Lifters/power athletes (baseball, football, soccer, non-distance track, and nearly all field sports): inability to relax or sleep well at night- Overtraining in power athletes or lifters results in an overactive sympathetic nervous response (the “fight or flight” system). If you’re restless (when you’re supposed to be resting), unable to sleep well, have an elevated resting heart rate, or have an inability to focus (even during training or practice), those are signs that your sympathetic nervous system is on overdrive. It’s your body’s response to being in a constantly stressful situation, like training, that it just stays in the sympathetic state.

3. Endurance athletes (distance runners, swimmers, and bikers): fatigue, sluggish, and weak feeling- Endurance athletes experience parasympathetic overdrive (the “rest and digest” system). Symptoms include elevated cortisol (a stress hormone that isn’t bad, but shouldn’t be at chronically high levels), decreased testosterone levels (more noticeable in males), increase fat storage or inability to lose fat, or chronic fatigue (mental and physical).

4. Body composition shifts away from leanness- Despite training hard and eating well, you’re either not able to lose body fat, or worse, you start to gain what you previously lost. Overtrained individuals typically have elevated cortisol levels (for both kinds of athletes). Cortisol, among other things, increases insulin resistance which, when this is the chronic metabolic state, promotes fat storage and inhibits fat loss.

5. Sore/painful joints, bones, or limbs- Does the thought of walking up stairs make you groan with the anticipated creaky achy-ness you’re about to experience? If so, you’re probably over training. Whether it be with weights or endurance training, you’re body is taking a beating and if it doesn’t have adequate recovery time, that’s when tendiosis, tendoitis, bursitis, and all the other -itis-es start to set in. The joints, muscles, tendons, and ligaments are chronicallyinflamed and that equals pain. Maybe it’s not pain (yet) but your muscles feel heavy and achy. It might be a good time to rethink you’re training routine…

6. Getting sick more often- Maybe not the flu, but perhaps the sniffles, a sore throat, or a fever here and there; these are signs your immune system is depressed. This can be a sneaky one especially if you eat right (as in lots of kale), sleep enough, and drink plenty of water (I’m doing all the right things! Why am I sick??). Training is a stress on the system and any hard training session will depress the immune system for a bit afterwards. Not a big deal if you’re able to recover after each training session… but if you’re overtraining, the body never gets it's much-needed recovery time. Hence, a chronically depressed immune system… and that’s why you have a cold for the 8th time in two months.

7. You feel like garbage- You know the feeling: run down, sluggish, not excited to train… NOOOOO!!!!! Training regularly, along with eating well and sleeping enough, should make you feel great. However, if you feel like crap… something is wrong.

Those are some of the basic signs of overtraining. There are more, especially as an athlete drifts further and further down the path of fatigue, but these are the initial warning signs the body gives to tell you to stop what you’re doing or bad things will happen.

Next time, we’ll discuss ways to prevent and treat overtraining.

Nutrition Tips For Those LOOOOONG High School Tournament Weekends

Tournaments! Weekend-long (sometimes longer) events where athletes play multiple games in one day with very short breaks between games. Definitely not long enough to get a solid meal in before the beginning of the next match. All of our baseball and volleyball players have, seemingly, an endless stream of tournaments during the club seasons; it blows my mind a bit.

Anyway, this can pose a problem when it comes to being able to fuel properly before/after games. The aim for this post will be to provide tips how to eat leading up to the tournament, during the tournament (i.e. between games/matches), and sample snacks to bring. One can make this a complicated subject (eat 23.5 grams of protein, 15.8 grams of carbohydrates, eaten during the half-moon's light for optimum performance), but it's not really. It's easier than tracking orcs through the plains of Rohan.

If you glean nothing else out of the post, glean this: EAT. REAL. FOOD. There's no magic bullet supplement that will enhance your performance any more than eating solid, real food regularly.

Leading up to the tournament:

For (at least) the week prior, ensure that your meals consist of REAL foods, that is, plenty of vegetables and fruits, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Conveniently, the same rules that appeared in the post Eating for Strength and Performance, apply here. Craziness. As I've said before, if you fill your tank with crap, you're going to feel like crap, thus leading to performing like crap. Simple yes? We live in an age where technology makes our lives "easier" (though I would argue against a few of the more recent inventions) yet eating, the most basic human need, is over complicated. Our volleyball and baseball player (and all our athletes!) will take their training to the next level if if they just ate real food. Practical tips on how to achieve this below.

During the Tournament:

The length of the competitive day (6, 8, 10 hours?!!) will, to a degree, determine what types and how much food to bring. Obviously, longer tournament days will require more food than the shorter days. Here are three main points to remember when seeking foods for between games/matches.

1. EAT. REAL. FOOD. (notice a theme?) Don't go to 7-Eleven and pick up a Slurpee and whatever else they sell there. (You should NOT find body fuel at the same place you find car fuel.) Grab some fruit, make some sandwiches, and bring plenty of WATER. We'll go over a couple of beverages down below, but the number one liquid you should slurp: good ol' water. Divide your bodyweight in half... that's how many ounces (MINIMUM!) you should be drinking. If it's hot, and sweat is soaking your garments, drink your body weight in ounces.

2. Choose food that you know will sit well in your stomach. If you never eat peanut butter and pickle sandwiches (though if you don't, I don't know what's wrong with you. Try it. But not on tournament day.), don't pack them. The combination of nerves and high activity doesn't provide the best situation to try new foods. Pack food that you know you can handle (I also recommend staying away from a lot of dairy and highly acidic foods/drinks as both can lead to upset stomachs during intense activity).

3. Pack a cooler. I know it's extra work, but you'll be glad you did when you're able to chow down on healthy, delicious and filling foods while your friends are relegated to protein bars, candy, and who knows what other food they scrounge up.

Practical Solutions:

What does all this look like? Fill in your preferred food choice utilizing this general template. Think of it as a nutritional MadLib.

Breakfast:

1-2 fist-sized Protein source (eggs, cottage cheese, lean meat, Greek yogurt) + 1/2- 1 cup of Complex Carbohydrate source (fruit, oatmeal, whole grain toast, sweet potato, beans, any kind of vegetable) + 1-3 Tablespoons healthy fat (nut butter, real butter, olive oil, egg yolks, 1/2 avocado, nuts, pumpkin seeds) + at least 1-2 fist-sized serving of vegetables!

As an aside, I made cauliflower cream of "wheat" (and you know I love my cauliflower) the other day for breakfast. I tried this recipe and I just found this one. I think the second one would be a tastier option; the recipe I tried still had a cauliflower-y aftertaste. Maybe I needed riper banana or something. Anyway, this is an example a creative way to incorporate vegetables in tastier ways. And make them a DAILY part of your diet.

Lunch:

1-2 fist-sized protein source + 1/2 cup/serving of carbohydrate* + 1-3 Tablespoons healthy fat + at least 1-2 fist-sized serving of vegetables!

Dinner:

You guessed it: 1-2 fist-sized protein source + 1/2 cup/serving of carbohydrate* + 1-3 Tablespoons healthy fat + (you guessed it) at least 1-2 fist-sized serving of vegetables!

Snacks:

The same composition as the meals, just take half the serving side. For example, a hard boiled egg and an apple would be perfect. If you want some ideas of various foods to try, check out my posts here and here for other, less publicized super foods that have a plethora of benefits to offer to the competitive athlete.

* the amount of carbohydrates will fluctuate depending on if you work out/practice that day or not (see linked post about performance nutrition for more information). Eat 1-2 extra cups of carbohydrates spread throughout the day if practice/workouts are on that day. The "carb-loading" tactic is not a good idea unless you're running an Iron Man. A huge pasta meal the day before a competition doesn't do much for you except make you feel really full and sick.

Here are some sample snack options that might do well during long tournament days:

- Fruits (always a great option) such as bananas, apples, oranges, kiwis, melon etc.

- Homemade granola (complex carbohydrate source)

- Trail mix- a healthy blend of nuts and seeds (to provide satiety) and dried fruit with maybe a little chocolate thrown in (because let's be honest, the M&Ms are the best part).

- Celery, carrots, sliced bell peppers, jicima slices (or any raw veggie) and hummus

- Hardboiled eggs (this is where the cooler becomes handy), deli meat, tuna fish, sardines (if you're ok with no one sitting near you while you eat)

- Sandwiches: meat/cheese or peanut butter variations

Beverages-

1. Water, water, and more water. Water is the oil that keeps the body's engine running smoothly. No water? The engine starts grinding and struggling, like Gimli over long distances, and eventually poops out entirely. Not a desirable result during a big showcase tournament.

2. Drinks like Gatorade and Powerade are ok, but don't make them the primary source of liquid. They're useful if there's copious amounts of sweating going on (to help replace electrolytes) but too often I see athletes downing multiple bottles, when really, 1 bottle should be plenty.

3. If there's a decent chunk of time between games/matches, chocolate milk is actually a pretty good option for providing carbohydrates and protein (both of which are needed after a workout). I don't recommend drinking if there's only 15-20 minutes between games as dairy can sometimes upset stomachs.

4. Soda = fail.

Do you see a pattern? By eating quality food throughout the week and during the tournament days ensures that your body has the proper fuel for competition. Matter of fact, eating this way ALL the time does wonders for your health and performance.

Think of it this way: leading up to the tournament, athletes practice and strength train to prepare their bodies to ensure they're ready to compete. Any coach would tell you that if you try to cram all those hours of practice in the day before the tournament, things won't work out so well. The exact same principle applies to nutrition. If eating nutritious food starts the night before, well, things won't work out so well. Be vigilant in your preparations and take care as to what goes in your body as diligently and enthusiastically as you practice for each tournament.

5 Tips for the Vertical Jump

As mentioned a bunch of times by now, our theme for this month on the blog is Training for Overhead Athletes. The holy grail of performance indicators for volleyball players is, without doubt, the VERTICAL JUMP and with good reason, the sport is won or lost in the air, so an athlete will clearly have the advantage the longer they can stay in the air to execute their portion of the play. Stevo did a great job talking about the pros and cons of the vertical jump as a test itself back in January 2012. You should check it out.

Now, if you read that post, you will clearly understand the limits of the test, but you may still be wondering "Okay, okay, Stevo... I get it. But can you PLEASE give me some tips on how to jump higher. I promise I won't vert test every day, nor will I ever allow my knees to cave!" Okay, since you've promised not to break the golden rules, I'll go ahead and give you my top 5 for improving your vertical jump. Please note, they are in order of basic to advanced:

- Get Stronger - you're entire body needs to be stronger to jump higher, but obviously some heavy emphasis on the lower body is required. And, NO, it's NOT your calf training routine that will make the difference. Think hips and hamstrings. You can pretty much read any other post on this site to learn how to do that.

- Try - yes, I'm throwing this out there: to jump higher, you must commit to doing so and that involves actually trying to achieve #1. Focus on it, embrace it, and it will happen.

- Practice Jumping Variations - Not just vertical jumping, but jumping in all planes of motion with as many variances as you can think of. And, for the love of your joints, please don't execute these with poor form and at 100% intensity/effort. You must be smart and your body will get much more from refining and perfecting technique than from being a hard-headed fool.

- Short Sprints - running is a plyometric activity, so add in some very short, high-intensity sprints.

- Consider Re-Working your Genetics - this is the "advanced" tip... what do I mean? At some point, you may need to acknowledge that your vertical jump dreams may not be achieved in 12-weeks and sadly (believe me, I know from personal experience) there's no amount of training that will fix the genes you were dealt. Once you realize it will be a tough road, go ahead and start back at #1.

Designing Practical Warm-ups for the Overhead Athlete

To give a brief recap, if you missed Stevo's post on Friday: August is dedicated to training means, modes, and methods for overhead athletes (these are sports like baseball, softball, volleyball, swimming, and javelin).

The pre-practice and pre-competition warm-up is extremely important for any athlete, but to an even greater degree for those athletes who need to give special consideration to the shoulder complex. As a strength coach, I've given numerous warm-up protocols to numerous athletes over the years and while, in a pinch, I could easily produce one that would be well-balanced and comprehensive, I've always preferred to plan my warm-ups in advance.

Preplanning ensures that every muscle, joint, angle, whatever has been taken into consideration and a decision has been made about how to address it for that day (or not). The important thing here being that you must give yourself the chance to make a decision about something ahead of time vs. simply overlooking the area.

Most coaches plan warm-ups on the fly, but like most things at SAPT, we tend not to do what "most" do... that's usually the easy way... and we know the right way! Thus, why we're the premier strength and performance training facility in the Fairfax, Tysons, McLean, Vienna areas.

Getting back to the practical warm-up: Over my time working with college athletes, I ended up developing an ever-evolving template of warm-ups that I would rotate and match to the first 15- to 30-minutes of the practice plan. For example, if the start of practice was going to be ripe with sprinting, the I would choose the plan to match. On the other hand, if practice was starting with quite a bit of hitting (volleyball) where I knew the shoulder needed to be totally warm and ready, then that would inform my warm-up choice.

http://youtu.be/IfJi8KLhtlg

This video is just showing the team warming up... keep that in mind while you watch the power + the height the guys are getting on the ball off one bounce. What's the warm-up look like before this part of the warm-up??? I bet it's a pretty good one.

Anything is an option: body resistance only, bands, medicine balls, actual sporting equipment (i.e. a baseball), weights, etc... Shoot, you can even use a sled/Prowler to do a fantastic total body warm-up that fully addresses the shoulders.

So, when planning a warm-up (or your own set of templated warm-ups) make sure you are addressing all the primary movers and in all directions - planes of motion - plus weaving in extra prehab that may not occur in the weight room and copious amounts of shoulder friendly mobilizations, stabilizations, and drills.

Intro: Overhead Athlete Basics

Note: Any time I use the phrase "overhead athlete" I'm referring to an athlete who's sport requires him or her to bring their arm(s) repeatedly overhead. The most common sports falling under this umbrella are baseball, volleyball, softball, swimming, tennis, and, perhaps the most awesome of the bunch, javelin.

In the wake of SAPT's inception, back in Summer of 2007, arrived the immediate realization that overhead athletes would be the predominant population we'd be coaching and training within the walls of our facility. In fact, you could have nearly fooled me if you told me that the only competitive sports in the Fairfax, Mclean, Tyson's Corner, Vienna, and Arlington regions were baseball and volleyball!

Sure, we had, and still have, the pleasure of working with a host of people from countless other athletic "categories" - field athletes, track, powerlifting, endurance sports, water polo, fencing (yes, fencing), and military personnel - overhead athletes were and still remain roughly 80% of the folks we get to work with at SAPT.

As such, given such a large and varied sample size, and years to work with these individuals, we've had ample time to manipulate X, Y, and Z training variables to accurately delineate which constituents of a sound training program are going to most efficiently and effectively help the overhead athlete feel and perform at their best.

Throughout the month of August, we at SAPT are going to dedicate our time to providing you with solid and applicable information that you can immediately employ, be you a strength coach, physical therapist, sport coach, or athlete. And hey, even if you don't do anything related to overhead sports, you can still pick up some quality gems related to vertical jumping, shoulder-friendly pressing variations, Olympic lifting, sprinting, and a plethora of other topics that will undoubtedly pique your interest.

The primary reason we are devoting an entire month to the topics of training and management of overhead athletes is that it remains abundantly clear that there still exists a unfortunate paucity of coaches - sport and strength coaches working with youth, amateur, Division I, or Professional athletes - who truly understand the unique demands overhead athletes face, and how to account for these demands both on the practice field and in the weight room.

Due to the awful tragedy of early sports specialization, and the lack of coaches and parents (despite being well-intentioned) who understand how to implement a sound, yearly training model (that includes time OFF the court or field), we are seeing injuries occur in players at the young age of 13 that didn't used to happen until the age of 25 (or ever). Baseball players are realizing too late that's actually not a good idea to throw year-round, and youth volleyball players are experiencing an unprecedented volume of upper and lower extremity issues that could have been prevented simply by taking a season to play a different sport, and/or immersing themselves in a solid strength & conditioning program.

The overhead athlete's arm and shoulder continually undergo insane stressors that need to be accounted for; and not only by the strength coach but the sport coach as well, as they control how many times in a practice an athlete throws, hits, or jumps.

Let's take just a quick look at what a baseball pitcher's arm is assaulted with every time he throws a baseball:

- His humerus (upper arm bone) undergoes internal rotation at roughly 7,200° per second. In case you're wondering, and would like a more scientific way of describing things: that is a crap ton of revolutions in a very short period of time. - His elbow has to deal with approximately 2,500° of elbow extension per second. - His glenohumeral (ball-and-socket) joint experiences about 1.5x bodyweight in distraction forces.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg, as we haven't even dived into the other demands the wirst, elbows, and shoulders face, let alone what occurs at all the joints below the shoulder.

These demands simply won't be attenuated by doing a few hundred reps of band work before and after practice, let alone throwing the athlete into the proverbial squat-bench-deadlift program overseen by the high school football coach.

Over the next four weeks, you can expect to find us discussing:

- Practical warm-ups for the overhead athlete

- Why power development for baseball, softball, and volleyball players needs to be approached differently compared to many other sports

- Olympic lifting for overhead athletes

- The truth about vertical jump training for volleyball players

- The myriad myths and fallacies surrounding "shoulder health" and "arm care" programs

- Biomechanical asymmetries - both undesired and desired - that accrue in an overhead athlete's body due to the inherent nature of the sport, and what to do about them

- Energy system training

- Nutrition for fuel during tournaments and game day

- And, of course, as many Star Wars and Harry Potter references that we can find room for

- And much, much, more

All of us at SAPT are looking forward to the next month together!